When Desire becomes Debt

Did you catch the second video of the Story Rules YouTube channel? 🙂

LaLast week, I had the privilege of visiting the iconic Kitab Khana in Fort, Mumbai and sign some books. I wrote a post about it.

I also wrote a post about how I almost missed edition #136 of this newsletter!

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Welcome to the one hundred and thirty-seventh edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

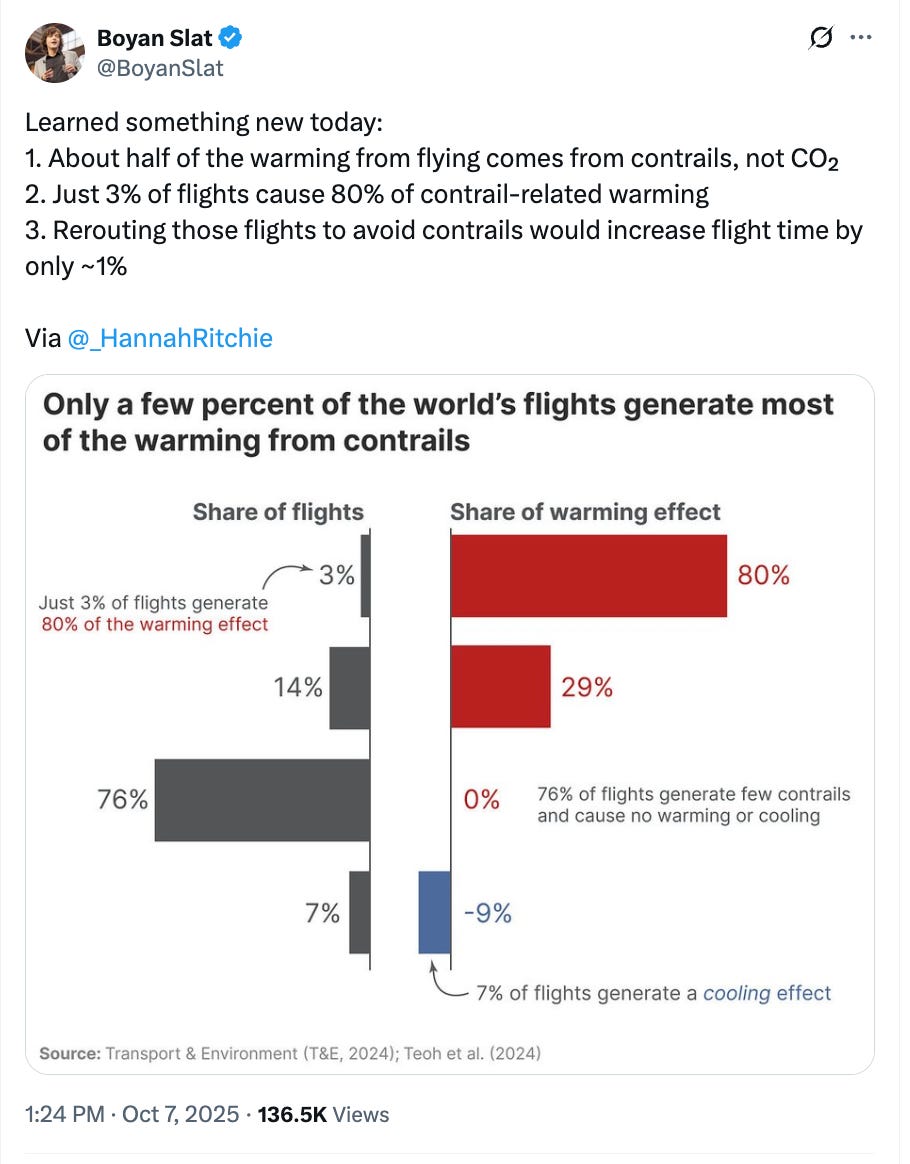

Fascinating stat, if true. Powerful example of the Pareto principle.

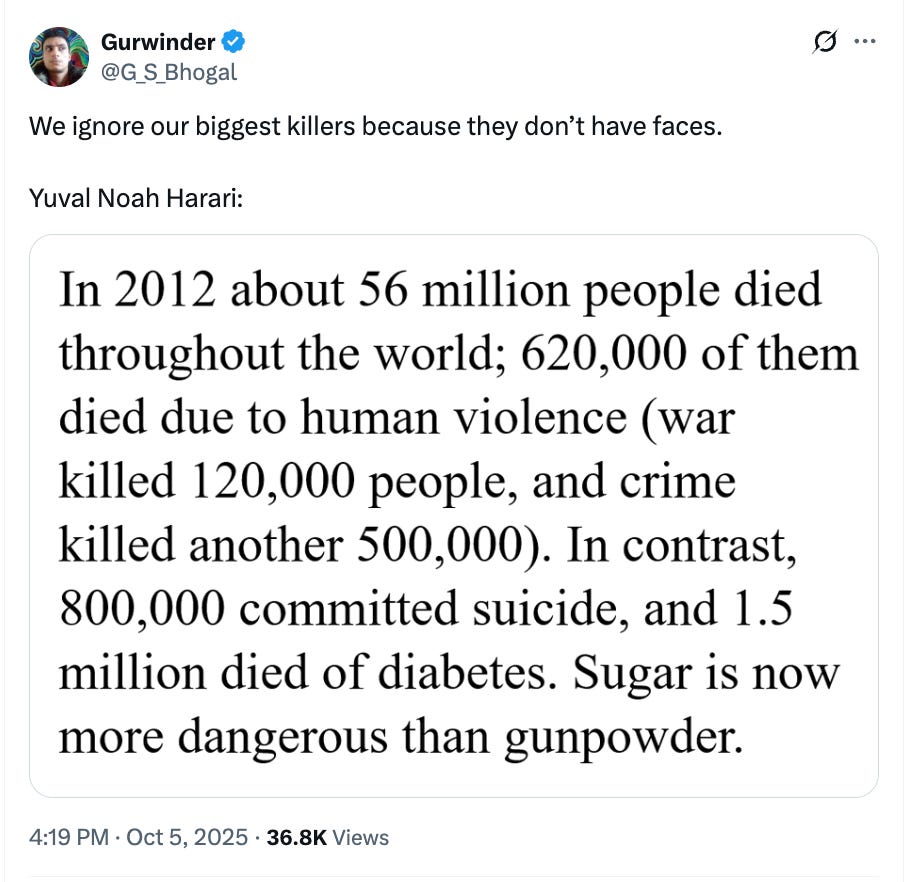

Great last line. Classic Yuval Harari.

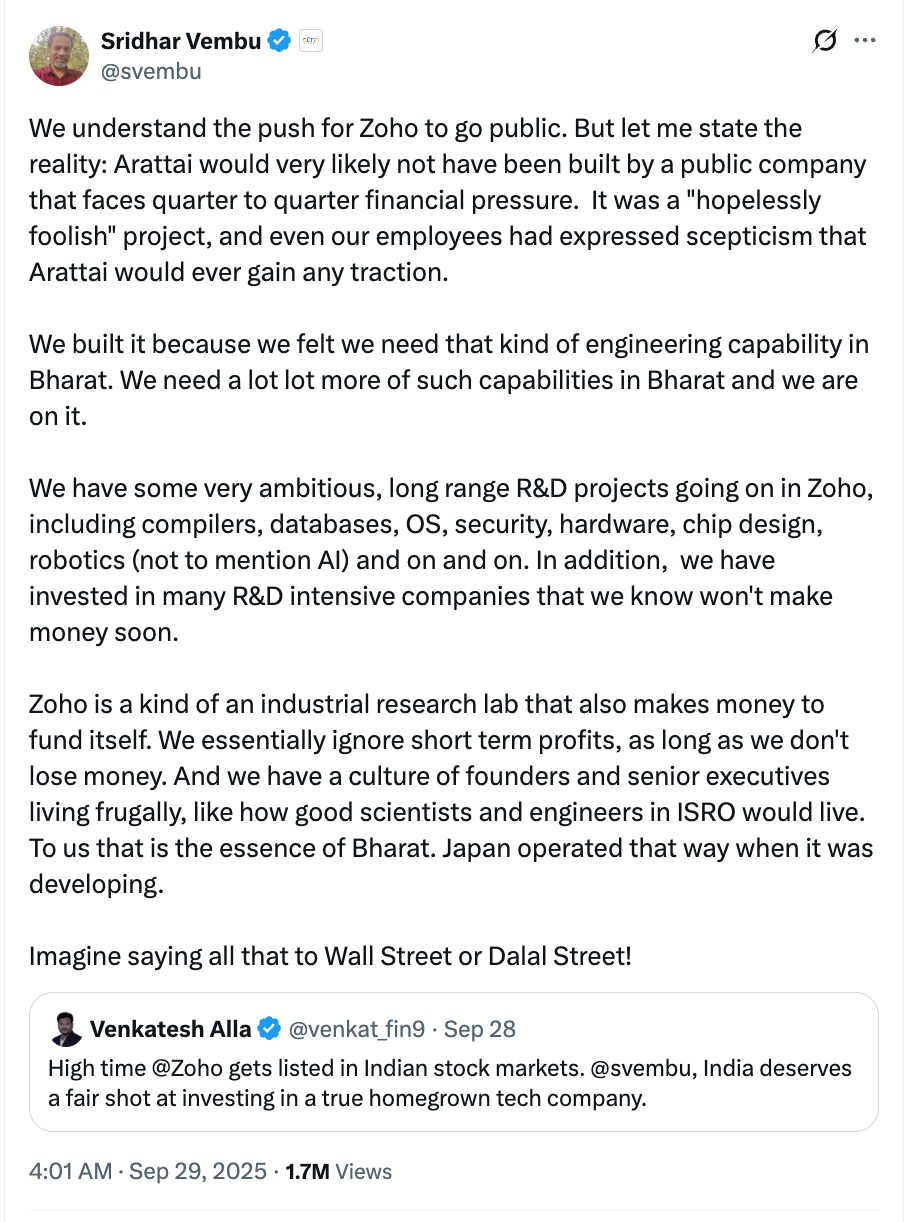

Zoho is a very interesting company. I’m not sure how Arratai will do, but you gotta hand it over to the team for the ambition and effort.

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘Self-Driving Cars Are Miracle Drugs’ by Derek Thompson

Derek Thompson is a superb storyteller. Notice how he makes the number 40,000 relatable (it’s a principle covered in Chapter 19 of my book, btw!):

Consider the number: 40,000. That’s about how many American men die each year from prostate cancer. It’s how many women die each year from breast cancer. Influenza killed about 40,000 Americans last year. So did Parkinson’s disease.

Imagine a biotech company announced that it had developed a vaccine that, if scaled nationally, could reduce the mortality rate of all these illnesses—prostate cancer, breast cancer, influenza, and Parkinson’s disease—by 90 percent. I think we’d call it a miracle drug.

The number, again: 40,000. It’s also how many Americans die each year from “traffic fatalities,” according to the US Department of Transportation.

Then there’s a simple use of norm-variance (Chapter 9!) to show the extent of the issue in the US:

Men in the U.S. die more than 5 years younger than those in Japan or Switzerland, and auto accidents account for 10 percent of this expectancy shortfall—more than diabetes, cancer, or suicide, according to a 2022 analysis by the USC researcher Jessica Ho.

Another lovely use of framing—had this happened in healthcare, it would be front page news:

Imagine, again, if some tech company announced that it had developed a product that, scaled nationally, could reduce the mortality rate of car accidents by 90 percent. I would like to think that we would consider it an absolute miracle.

Except, it exists. It’s Waymo—a driverless taxi service.

The safety stats of driverless vehicles are quite stunning, if true:

But many US states are not too welcoming about this innovation:

So, why are so many progressive cities trying to prohibit Waymo cars, as if they were fentanyl on wheels? Timothy Lee writes that a number of Democratic-leaning states “are considering proposals to restrict or ban the deployment of driverless vehicles.”

And I like how Thompson draws a parallel between these Democrat leaders and Republican anti-vaxxers:

Feel the irony: Partisans blocking a healthy, life-saving technological invention due to fanatical precautions about unintended effects. These Democrats are the mirror image of vaccine-skeptic conservatives who stand athwart progress yelling stop in the realm of therapeutics.

b. Nancy Duarte on the importance of contrast

Contrast is one of the most important techniques on storytelling (Chapter 10 of the book). Duarte lists three types of contrast that can be used in any work story. The first one is problem-solution:

#1: Problem-Solution

Start by establishing a specific problem your audience faces, then reveal how your solution directly addresses it. This builds urgency before positioning yourself as the cure.

In my TED Talk, I used this framework to demonstrate how presentations often fail to move audiences. I first established the problem: many presentations lack emotional impact and fail to inspire action.

Then I revealed the solution: a specific structure behind history’s great talks that creates contrast between the audience’s present reality and their desired future.

Check the post for 2 other forms of contrast.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

Two of my favourite storytellers – Derek Thompson and Morgan Housel – come together in this episode to discuss Housel’s new book, ‘The Art of Spending Money’.

Thompson sets up the discussion nicely, with a contrasting set of statements about how the US is rich, but not necessarily happy:

America is rich. And decades of economic research tell us that rich countries are happier than poor countries.

The 2025 World Happiness Report ranked the US 24th in average life satisfaction. Its lowest position ever. Americans have bigger houses, faster phones, better health care than ever before.

But we eat more meals alone, trust our neighbors less, scroll endlessly through other people’s perfect lives. As one study put it, social connection, not GDP, is the real ultimate driver of happiness.

He then quotes Housel and diagnoses that while some people might be good at earning money, they may not be skilled at spending it:

As the finance writer Morgan Housel sees it, something else is happening. Americans might be the best country in the world at generating income, earning it, but we’re not world class in spending it to buy happiness.

In fact, Housel says, Americans are unusually burdened by a special kind of debt. Not normal debt, not the debt you can see on mortgage statements or auto loan records. We’re burdened by an invisible debt, which is social comparison and desire.

Desire is a hidden form of debt, Housel says. You don’t track it. It’s not on your balance sheet.

‘Desire is debt’ – that’s a simple yet powerful reframing.

Housel digs further into how social media is fuelling an avalanche of ever-increasing desires:

… a lot of it is kind of the modern marketing system that tells you in a shout what you should want, how you should live. That has always been true. It is true on steroids in the last 15 years because of social media, where now it is just being absolutely bombarded 24-7 with pictures, images, stories, ideas of how you should live and constantly bombarded with a feed of people who are seemingly, which is an important word, happier, prettier, more successful than you are, mainly because of the image that they are portraying to the world.

Housel makes an interesting point – he believes that money amplifies your current state of happiness (or lack thereof):

…if you are already a depressed and anxious and sad person, it is very unlikely statistically that earning more money will make you happy. If you are already, if you are starting out as a happy, joyful, sleeping eight hours a night content person, then money can be like a leverage on your personality.

He then says that humans should know the real purpose of money – not to buy things to increase your status, but to get time so that you can spend it with your loved ones:

Once I came to terms with that, then I think it was easier for me to want to use money for what I think is its highest purpose, which was independence. I didn’t want to use money for flashy stuff to get the attention of strangers.

I wanted to use it for independence, so I could wake up every day and say, I can do whatever the heck I want today with the people whom I want to spend time with.

Our attention is a more scarce resource than money. Thompson uses a simple analogy of a jug of water to bring it alive:

Thompson: … my attention is a little bit like a finite jug of water, and every day, I have a choice to fill up certain glasses, and my wife is one glass of water, and my child is another glass of water, and all the people who hate me on Twitter are another glass of water. And if there was some way to account for whose glass held the most water at the end of the day, and this account was like read back to me as clearly as like my Oura ring data or something, I think some days would be astonishingly embarrassing, just how much water I poured into the glass of people I don’t care about, and I don’t love.

Housel: While your wife and daughter were dehydrated in the corner, right?

Thompson: Well, I’m dehydrating my poor daughter. That is exactly it. It’s been a while since I thought of that concept, and I don’t think I’ve talked about it on this show, but it’s a concept that I started being very purposeful about. Whose cup am I filling? I only have so much water in any given day. Attention is literally the most finite resource.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash