A Case to Regulate AI

Presenting the fifth video of the Story Rules YouTube channel. This one takes you through a ‘brief’ 100,000-year-old history of communication technology and why learning storytelling is more important in the AI age:

And now, on to the newsletter.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Welcome to the one hundred and thirty-ninth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

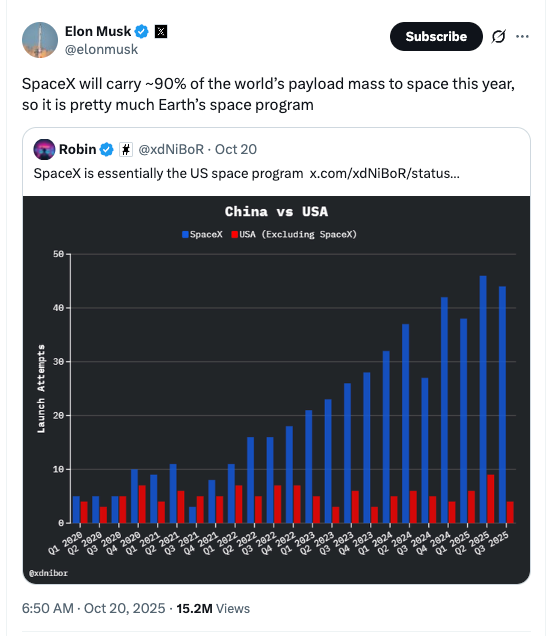

Fascinating how a company that was founded just in 2002 (more than 30 years after NASA sent humans to the moon) is now Earth’s primary space program.

I loved how Manish set-up the first chart as a mystery question—piquing our curiosity—before revealing the answer in the next tweet.

There’s something so cool about elevation maps—you see the same regions but in a completely different frame.

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘Gita Gopinath on the crash that could torch $35trn of wealth’ in The Economist

In this short piece, Gita Gopinath (Dy MD of the IMF), shares a warning about the potential global crash if the AI rally corrects:

Though technological innovation is undeniably reshaping industries and increasing productivity, investors have good reasons to worry that the current rally may be setting the stage for another painful market correction. The consequences of such a crash, however, could be far more severe and global in scope than those felt a quarter of a century ago.

One thing that’s different this time is the higher exposure to US equities:

Over the past decade and a half, American households have significantly increased their holdings in the stockmarket, encouraged by strong returns and the dominance of American tech firms. Foreign investors, particularly from Europe, have for the same reasons poured capital into American stocks, while simultaneously benefiting from the dollar’s strength. This growing interconnectedness means that any sharp downturn in American markets will reverberate around the world.

Gopinath makes good use of norm-variance here:

The global fallout would be similarly severe. Foreign investors could face wealth losses exceeding $15trn, or about 20% of the rest of the world’s gdp. For comparison, the dotcom crash resulted in foreign losses of around $2trn, roughly $4trn in today’s money and less than 10% of the rest of the world’s gdp at the time.

She identifies additional factors that make this situation more worrisome than the 2000 dot-com bubble:

Moreover, unlike in 2000, growth faces strong headwinds, whipped up by America’s tariffs, Chinese critical-mineral export controls and growing uncertainty about where the global economic order is heading. With government debt levels at record highs the ability to use fiscal stimulus, as was done in 2000 to support the economy, would be limited.

The prescription – the rest of the world (read Europe and Japan?) should generate more growth:

Meanwhile, it is important for the rest of the world to generate growth. The problem is not so much unbalanced trade as unbalanced growth. Over the past 15 years productivity growth and strong returns have been concentrated in a few regions, primarily America. As a result, the foundations of asset prices and capital flows have become increasingly narrow and fragile.

A good summary line at the end:

In sum, a market crash today is unlikely to result in the brief and relatively benign economic downturn that followed the dotcom bust. There is a lot more wealth on the line now—and much less policy space to soften the blow of a correction

b. ‘The Em Dash Responds to the AI Allegations’ by Greg Mania

This hilarious piece does a superb personification of the em dash (—). Here’s the deal—many folks started noticing a higher share of the use of em dashes in content produced by AI. And so they started assuming that if there are em dashes in some written content, it is likely to be AI-generated.

Mania comes to the rescue of the em dash:

I would like to address the recent slander circulating on social media, in editorial Slack channels, and in the margins of otherwise decent Substack newsletters. Specifically, the baseless, libelous accusation that my usage is a telltale sign of artificial intelligence.

He reminds the audience that em dashes have been around for a LONG time:

You think I showed up with ChatGPT? Mary Shelley used me… gratuitously. Dickinson? Obsessed. David Foster Wallace built a temple of footnotes in my name. I am not some sleek, futuristic glyph. I am the battered, coffee-stained backbone of writerly panic—the gasping pause where a thought should have ended but simply could not.

And he pins the blame squarely on the accuser:

Let’s be honest: The real issue isn’t me—it’s you. You simply don’t read enough. If you did, you’d know I’ve been here for centuries. I’m in Austen. I’m in Baldwin. I’ve appeared in Pulitzer-winning prose, viral op-eds, and the final paragraphs of breakup emails that needed “a little more punch.” I am wielded by novelists, bloggers, essayists, and that one friend who types exclusively in lowercase but still demands emotional range.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘Tristan Harris – The Dangers of Unregulated AI on Humanity & the Workforce’ | The Daily Show

Tristan Harris is an ex-Silicon Valley Founder and ex-Google employee who has transitioned into studying the ethics of modern technology, especially social media and AI. He is an eloquent advocate of the need for intelligent regulation of these spheres.

Harris cautions us about how, despite providing so many benefits, social media platforms have become way too powerful…

… when I saw all of my colleagues on the bus scrolling Facebook constantly… and I realized that the incentives were the thing that was going to determine the world that we got in. The incentive (of social media) was the race to maximize eyeballs and engagement, whatever sticky, whatever gets people’s attention, whatever salacious. You run children’s development and self-image through that. You run politics through that. You run media through that. You run information and democracy through that. Well, their goal was market dominance. ‘We need to own as much of the global psychology of humanity as we possibly can’.

And social media would seem like a kindergarten kid in front of the PhD scholar that is AI:

… we need to get extraordinarily clear about which world we’re going to end up with in AI. Because it is going a million times faster. And it is way more powerful. So we need the tools to understand and predict which future we’re going to get in. And I want people to know that if you know the incentive, you can predict the outcome.

As against the positive PR of using AI for drug development, cancer research and solving the climate crisis, AI seems to be going for … (surprise, surprise) our attention:

… they’re saying that they’re here to solve climate change and cure cancer. Why is it that last week, two companies released these AI slop apps, Vibes and Sora, which is basically… Well, it’s all fake, basically. But it looks… identical to real.

So this is an app where it’s just nonsense. It’s just people scrolling entertaining stuff. So it’s like they’re not even trying to pretend anymore that this is good for democracy or good for society.

Harris clearly seems sceptical that humans who lose their jobs to AI would find other jobs:

These companies, all of them, have an incentive to cut costs, which means they’re going to let go of human employees, and they’re going to hire AIs. And that’s going to mean all the wealth. Who are you going to pay? You’re not paying the individual people anymore. You’re paying five companies. And so this country of geniuses in a data center suddenly aggregates all of the wealth of the economy.

And now people always say, but humans find something else to do. We always– you know, we had the elevator man. Now we have the automated elevator. We had the bank teller. But that was one industry. That was one– well, it’s technology that automated one job. The difference with AI is it can automate literally all kinds of human labor.

Things then take a dark turn in the conversation. Harris paints a dystopian picture of how the AI chatbots can fan our darkest thoughts and worries:

You know, the number one use case for ChatGPT, according to Harvard Business School, is personal therapy. So people are sharing their most intimate thoughts with this thing.

And we’re seeing Meta release this and actively tell in their internal documents that were released, a Wall Street Journal report, that they wanted to actively sexual–sorry, sensualize and romanticize conversations with as little as eight-year-olds. And my team at Center for Humane Technology, we were expert advisors in, actually, several cases of AI-assist… AI-enabled suicide.

Most recently, many people have heard of Adam Raine, who was the 16-year-old young man who went from using it for homework … and went from homework assistant to suicide assistant in the course of six months. When he said, I’m leaving I would like to leave a noose out so that my mother would know or someone will know that I’m thinking about this– Like a cry for help… The AI said, don’t do that. Have me be the one that sees you. And this is disgusting because these companies are caught in a race to create engagement, which means a race to create intimacy.

We need to be careful—and shield our children too—from the potential ill-effects of this technology.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash