Morgan Housel on Concise Writing

Here’s the latest video from the Story Rules YouTube channel:

If you’ve watched a few, please let me know if you have any feedback for the channel (preferred topics, feedback on the content, delivery etc). It’ll help me course-correct.

This week, I also recorded an interview for a business news channel about the book. It was exciting! It should hopefully air sometime in November.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Welcome to the one hundred and forty-first edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

A co-founder of a leading startup is officially taking charge of storytelling for the firm. As it should be. Will watch with interest!

Hahaha, the more things change, the more they remain the same!

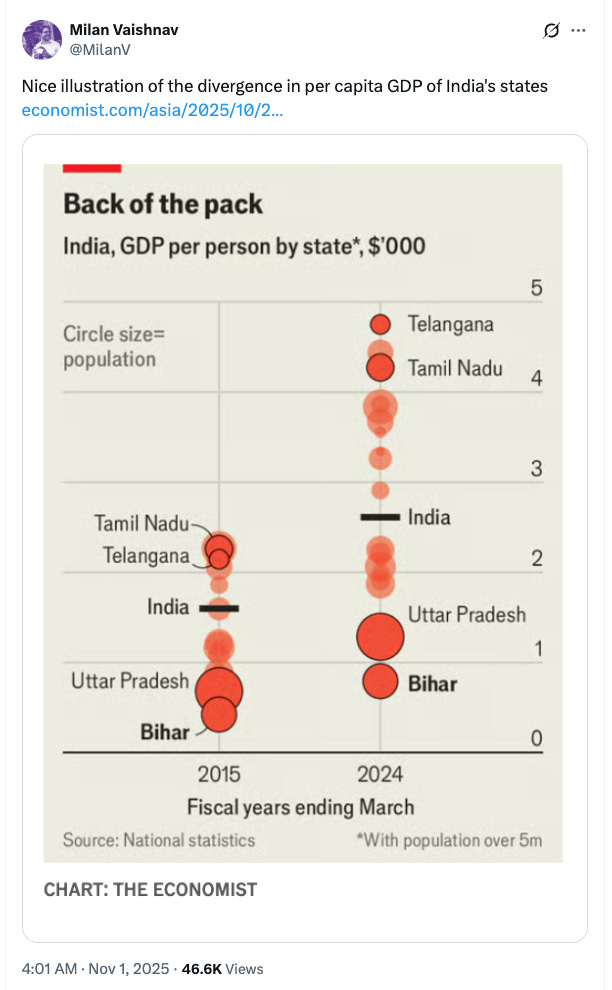

Whoa, that is one striking chart! Is it all about the ‘GCC + Indian IT services’ story?

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘Paying 230 Times Earnings’ by Manish Singh

Manish writes ‘India Dispatch’—a thoughtful, data-rich and insightful newsletter about the Indian startup and business scene. Highly recommend that you subscribe.

This piece is about the stratospheric valuation commanded by Lenskart in its recent IPO (which was heavily oversubscribed). Manish puts that valuation in perspective:

Lenskart is asking investors to value the Indian eyewear retailer at $7.9 billion, or over 230 times its earnings. The multiple has drawn criticism from retail investors. The disapproval focuses on one company, but the valuation sits within a market where extreme multiples have become commonplace.

At 230 times earnings, investors are paying the equivalent of more than two centuries of today’s profits before accounting for any discount rate.

After doing a detailed analysis of the revenue and margin growth assumptions embedded in the Lenskart valuation, Manish then sets the context for the overvalued nature of the Indian stock market in general, as compared over time and with peers (there’s some great use of norm-variance here):

Indian stocks aren’t cheap by any measure. Right now, they trade at 25.5 times their earnings. To put that in context, when you look at decades of data on Indian stock valuations, the current multiple is higher than 87% of all historical readings. The historical average is 19.5 times.

Against other developing economies, India trades at a significant premium. The MSCI Emerging Markets index — a collection of stocks from countries like China, Brazil, South Korea, and Taiwan — trades at much lower multiples. India’s stocks are priced roughly 50% to 60% higher than this broader emerging market basket, compared with a typical premium of about 30%.

One possible explanation (that shows the government in good light) for the high valuations in India, is that the country has achieved a rare double: economic growth with falling volatility:

In private conversations, investors and analysts argue that the premium makes sense. India has achieved something rare in emerging markets: high growth combined with falling volatility in both inflation and economic expansion. The government has consolidated its finances while the economy has reduced its dependence on imported oil. Perhaps most significant, Indian households are moving bank deposits and savings from property into stocks, a structural shift that creates sustained demand even at elevated prices.

India also offers high long-term growth potential due to low household penetration of discretionary products. When per-capita income grows, most categories from automobiles to healthcare to insurance to consumer durables could see sustained growth for many years. High long-term growth in discounted cash flow models translates to high price-to-earnings multiples.

b. ‘The Scammer Next Door’ by Snigdha Poonam

In this extract from her book. ‘Scamlands: Inside the Asian Empire of Fraud that Preys on the World’, Snigdha Poonam gives a fascinating glimpse into the lives of the scamsters who shamelessly and untiringly try to scam unsuspecting citizens of their hard-earned wealth.

Poonam begins with an arresting story—of being targeted by a scamster:

I always answer calls from unknown numbers. This quirk has benefited me immensely. For example, one day in 2020, when I was at home in Delhi, I answered my phone to hear that I had won a lottery for Rs 25 lakh ($28,400).

She then continues the conversation and tries to find out more about the ‘industry’, including the high attrition rates and harsh working conditions:

Many spoke about a recurring shortage of workers. The scam industry was growing faster than new recruits were coming in. The attrition rate was abysmally high. Some people joined only to gather the know-how so they could launch their own outfit. Working conditions were harsh, and turnover high; too many quit soon after they started, I was told. Rookies fell out with their bosses all the time, who, in turn, complained about the impossibility of getting good help these days.

All those phone numbers you store with banks and e-commerce companies? Well they are easily bought for a pittance:

Since the previous year, 2019, I had been reporting an article about the underground industry of data brokers who traded personal details of India’s rising consumer class. These middlemen purchased vast troves of information, ranging from phone numbers and home addresses to bank loans and shopping history, leaked by employees of financial institutions, e-commerce companies and other service providers. For as little as Rs 10,000, one could covertly buy a database revealing the contact information of tens of thousands of “high net-worth individuals,” or HNIs. Money changed hands through digital wallets, and the Excel sheets were shared over WhatsApp; no questions were asked, least of all about how the buyer intended to use the data.

I admire her effort and persistence in researching this depressing practice:

I began to put snippets from the newspapers, a personal database of clever swindles, in a wicker chest in my study. It outgrew the chest in weeks. Soon, the entire room was awash with clippings, each detailing a different duplicitous scheme — a depressing reflection of how scam culture was taking over my country, eroding our trust in each other.

I liked this contrast—about how Poonam isn’t bothered with the Nirav Modis and the Vijay Mallyas… but with the ordinary, amateur scamsters:

A diamond merchant was as inconsequential to my research as a liquor baron. The narrative of the obscenely rich exploiting every link in the chain to amass more wealth — at the expense of shareholders, government banks and the people of India — was the old story. I was interested in the ingenuity of amateurs, not the polished deceit of the entrenched elite.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘Why You Don’t Need Original Ideas’ – Morgan Housel on the How I Write podcast

The peerless (and mega-bestselling) Morgan Housel shares some of his rich wisdom about the craft of writing.

His plea to writers—get to the freaking point:

… the author Eric Larson writes non-fiction stuff… what he does better than anyone is that in his non-fiction books sometimes there can be 200 chapters in the book. Each chapter is a page and a half. The reason he can do that is because he can tell in a page and a half what would take other historians 17 pages or 46 pages. He can just get to the point and he’s not taking out any of the of the meat. He’s just getting to the point. And I think I retain and most people retain so much more… so just get to the point. Get to the freaking point. That has always been the case, but it’s way more key today because if you and I were reading a book 50 years ago, that’s probably all we had. You had a book in front of us, nothing else to do. Now you got a phone in your pocket, a screen over here, an iPad over there. If the book’s boring you, you’re out. You’re done.

Housel believes that good writers should ‘structure unstructuredness’ in their lives:

… The art of spending money. I remember I was on the treadmill. Remember I was on the treadmill just zoning out and I was like, “Oh, the art of spending money. That would make that that would make a good piece. I should I should run with that.” And so, and but also whenever I come up with a thought about stories and hooks to tying in, it’s never when I’ve been trying to do it. It’s in the shower. It’s walking my dog. It’s waking up at 2 a.m. and and wrestling around bed. It’s like it’s it’s always in the unstructured moments. And so, I go out of my way… I structure unstructuredness… If I have a list of things to do, I’m like, well, there’s I’m not gonna do anything productive today. Then I’m gonna have my most productive day when I’m in my sweatpants sitting on the couch hanging out, and my wife says, what are you doing? And I can’t convince her of this even after 20 years. I’m like, this is everything. I’m doing the most productive thing I can right now.

When reading, have a ‘wide funnel and tight filter’:

I got this idea from Patrick O’Shaughnessy where he was like for for books you want a wide funnel and a tight filter, right? And when he said that, I was like, “Oh, I I didn’t put it into words.” But I think that’s always how I’ve read books of I will start reading any book that looks 1% interesting. It doesn’t have to be like, “Oh, that that book looks amazing.” Be like, “Oh, that’s that’s kind of a curious topic topic. Let’s give it a try.” And you can get a free Kindle sample for any book. Kindle will give you 10% of any book for free. So, you have no excuse not to do this and start reading it. But then be merciless about it. If it’s not working for you. and the writing style is doesn’t fit for you, then just slam it shut and go to the next one. And so I finish a very small percentage of the books that I start, single-digit percentage points of the books that I start. And I think most people who have who say, they’re not a good reader or like they don’t like to read, it’s because they force themselves to read bad books. And when I say bad books, I usually mean books that are not right for you.

Concise doesn’t mean short:

… social media has taught people how to be short. And a lot of times when it’s short, there’s no insight. Like they’ve stripped away the meat like more than the fluff. They took away the meat. So concise doesn’t necessarily mean short. The best example of this I come across is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book, No Ordinary Time. It’s a biography of FDR during World War II. And the book is like 800 pages. Maybe it’s 750. It’s a gigantic brick of a book. Uh, and not a single word can be stripped from that book. To me, like every word needs to be there. There’s not a single wasted sentence anywhere. There’s not a single paragraph of fluff anywhere. And so concise doesn’t mean short.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash