The Educate Girls story

Last Sunday, I was part of a small talk and panel discussion at the IIJS (India International Jewellery Show) 2026, organised by the Gems and Jewellery Export Promotion Council. (I was clearly invited there for my storytelling skills, given I own exactly zero pieces of jewellry)

The panel was moderated by the energetic Anil Prabhakar, who ensured that my book was gifted to each of the panelists.

Here’s a video recording of the event. Anil is a captivating storyteller himself—notice how he uses movie references and clips to make his points!

(Warning: some singing by me involved).

And now, on to the newsletter.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Welcome to the one hundred and fifty-first edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

Powerful label. For the longest time I would be in the eristic mode, especially when arguing with friends. In the last few years, I have tried to move to the dialectic (not calling it by those labels of course). But its not easy… the ego and confirmation bias are challenging hurdles.

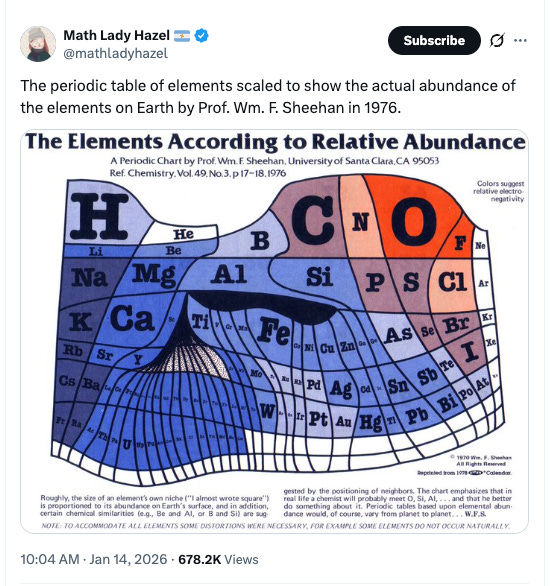

Cool chart, especially for chemistry geeks.

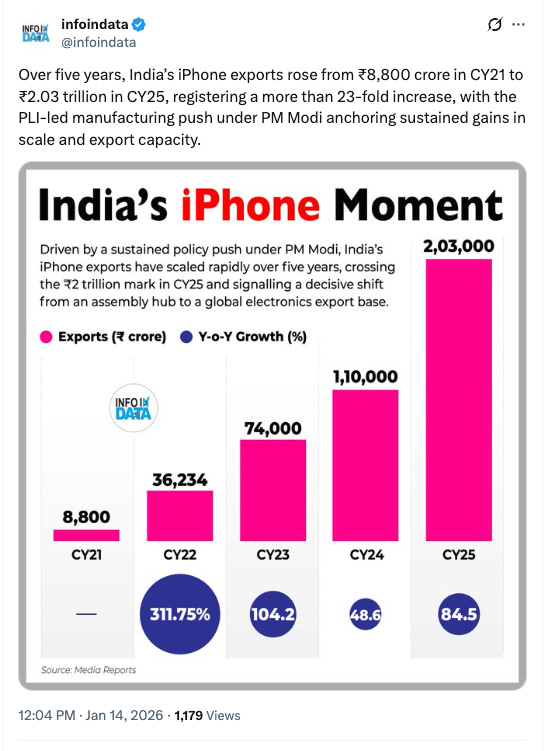

This is stunning if true. The numbers seem almost fantastical. Any catch in this story?

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘Capital in the 22nd Century’ by Philip Trammel and Dwarkesh Patel

The authors start with Thomas Piketty’s core argument from his epochal book, ‘Capital in the 21st Century’:

In his 2013 Capital in the Twenty-first Century, the socialist economist Thomas Piketty argued that, absent strong redistribution, economic inequality tends to increase indefinitely through the generations—at least until shocks, like large wars or prodigal sons, reset the clock. This is because the rich tend to save more than the poor and because they can get higher returns on their investments.

They then contrast it with data saying that labour has self-corrected through higher wages… in the past. But the same cannot be said about the future:

Historically, however, income inequality from capital accumulation has actually been self-correcting. Labor and capital are complements, so if you build up lots of capital, you’ll lower its returns and raise wages (since labor now becomes the bottleneck).

But once AI/robotics fully substitute for labor, this correction mechanism breaks.

In the AI age, the bulk of returns seem to be cornered by those with access to capital:

A lot of AI wealth is being generated in private markets, which only large and sophisticated investors have access to. You can’t get direct exposure to xAI from your 401k, but the sultan of Oman can. This trend toward the “privatization of returns”, already ongoing (1, 2, 3) and especially pronounced in the AI startup world, could well continue indefinitely.

The rest of the article paints a bleak picture of the rising power of capital and how there may be a need for stronger redistribution (through wealth taxes et al) to address the imbalance.

A widely celebrated byproduct (and cause) of the Industrial Revolution was the shift in wealth and ultimately political power away from a hyper-conservative, decadent landowning aristocracy to a bourgeois middle class that prized experimentation, thrift, and hard work. For better or worse, once the robots are doing all the work, wealth and power will shift again. Whether the optimal distribution of capital in the 22nd century is equal or otherwise, we can agree with Piketty that it may not emerge by default.

Monga is one of my favourite writers from the stellar ESPNCricinfo universe. In this provocative piece he starts with an attention-grabbing incident from the Perth test that India won:

Something unprecedented happened during the Perth Test of 2024-25. India still needed seven wickets to beat Australia when, at the end of the third day, cricket journalists’ inboxes chimed with a press release from a PR firm that manages communications for quite a few franchises, including those in the IPL.

This was no ordinary press release, a tool otherwise meant to convey news for wider publication. This was an opinion piece crediting coach Gautam Gambhir for “backing” Virat Kohli, for promoting KL Rahul to open the innings in the absence of Rohit Sharma, and for selecting Harshit Rana and Nitish Kumar Reddy.

Monga then uses norm-variance to distil what was unique about that press release:

Jasprit Bumrah, the captain of the team and the bowler who delivered India the win, was not mentioned even once. This was quite an extraordinary event in cricket, more so Indian cricket: a coach being pushed as the face of the team.

Then he contrasts it with the negative press that Gambhir has received for India’s abysmal recent home test performances:

A little over a year later, having overseen India’s second home-series loss in 12 months after the team went 12 years unbeaten, Gambhir finds himself at the receiving end of fans’ ire for anything that goes wrong.

He expresses some sympathy for the bad results and mentions other contributing factors:

There are so many things that go into a Test result that the coach can do only so much. We are now witnessing the first generation of players that didn’t grow up knowing Test cricket is a non-negotiable. Perhaps the best talent in the country is now a more natural fit for limited-overs cricket. These series defeats are also a reminder of how relentlessly good R Ashwin and Ravindra Jadeja were.

Some more norm-variance to describe Gambhir’s high relative power:

Gambhir is the most powerful coach India have ever had. Greg Chappell had to face the might of player power, Duncan Fletcher was reduced to a rubber stamp, Ravi Shastri always deferred to Kohli, and Rahul Dravid was happy to be in the background. By all accounts, Gambhir hasn’t even had to use his political currency to achieve that.

He ends with an appeal to all parties to come together, introspect and figure out a way forward:

The way ahead is not drastic populist moves, but the more painstaking process of coming together of the selectors, the captains, the board and the coach to work out a way forward. As a bonus, they might all find some personal growth in the process.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

Educate Girls, founded by Safeena Hussain won the prestigious 2025 Ramon Magsaysay Award (often called Asia’s Nobel Prize) for its work on female literacy, becoming the first Indian organization to receive this honor.

Gayatri Nair Lobo is an excellent storyteller herself and does a great job describing the challenges faced by them and how they are tackling it.

Lobo shares the remarkable story of how founder Safeena Hussain was keen on scale from the start:

So Educate Girls was founded by Safeena Hussain back in 2007 in the district of Pali in Rajasthan in 50 schools… when you normally say pilot [program], you think one school, two schools. But … she upfront said (this) needs to scale and I need to design for scale. When we were thinking about where to work as an organization, Safeena went to the government of India and said, This is the kind of work I want to do. I want to work on girls’ education. She herself had a break in her education, and so this was something that was deeply meaningful.

Lobo shares the heart-rending story of a girl called Puja, who could not go to school because of family constraints (bear with me, given this is a longish extract):

So, the first girl that I met was this girl named Puja… Puja was 13 years old, or rather is 13 years old, and had never been to school. Ever, right? And we are sitting right outside her house. I’m saying house, but it was maybe eight feet by eight feet, no furniture. They lived out of plastic bags, like their clothes were rolled up in plastic bags, maybe three utensils and firewood. That was what the interior of her home looked like. And I asked Puja in Hindi, like, would you, don’t you want to go to school? And she said, “I would if they’d let me.” And so, in my head, I was like, oh my gosh, they’re now letting her go to school. So, we started speaking to the parents and realized that the parents were migrants who worked on a farm in another state. So, for nine to ten months of the year, they’re not in Madhya Pradesh where we were. They had to migrate to this other state, they’d work there, they’d take their three daughters with them. Puja was the oldest of their daughters. And he said, “Of course I want to send my daughter to school, but how? Like I can’t leave her here alone, it’s not safe.” And that’s when it hit me that, you know, he is not coming from a place where he doesn’t want to send his daughter to school. He’s just worried about her safety, like any other father would. It was just poverty. And so, we were trying to figure out different ways. Can she stay with her, you know, uncles or somebody else? And they said, no, they’re all migrant laborers. We did find a solution where we were able to enroll her in a government residential school. But that, I’m cutting to the end of the story, but the fact is they didn’t have documents for her. Getting her Aadhar card would have taken a few days of them missing out on work. So, it was really hard. The team stepped in, of course, and got all of that done, but the only thought in my head was that if she doesn’t go to school this year, she’s going to be outside of the RTE purview and she’s going to go through life never having gone to school. And I have kids the same age. And I just, this is a thought of how different their lives are just by that sheer luck of what family you are born into.

She distils the problems being faced by girls education into three key factors:

…three points, all starting with P. So, the first I told you about poverty. Right? It’s really hard to get somebody who’s focused on just getting a meal in front of their family to say, Hey, what about your daughter’s education? So that’s one. I mean, one is migrating for work, the other is the girl herself working because they need to feed their families. Or the entire family’s working and this girl is in charge of the younger siblings. Right? So, poverty is one. The second P is patriarchy. Why should I bother educating my daughter? She’s going to get married and live in another family anyway. Let me make most use of her now while I have her. There are still enough cases of young girls below the age of 18 who get married. And therefore, that’s the end of their schooling. There’s this mindset that, oh, if a girl goes to school, she’s going to get too big for her boots and she’s going to start, you know, answering back. And why should I have that? So, there’s all of those mindset issues that I’m clumping under patriarchy. And the third is policy. Like for school admission, I need to have an Aadhar card. A lot of these guys don’t actually have other cards, or they have mistakes on their other card, and they could not be bothered to go and get it changed. So, our team then has to help them do that. For like I said, there aren’t enough secondary schools. Right? That’s a policy issue. Not all states have open schools where girls can do their exams remotely, or rather their studies remotely. So those kind of policy issues I would say on the on the supply side exist.

Lobo gives a powerful example of how a simple policy change (getting states to start their own free open-schooling initiative, rather than relying on the National Open School system) can have an impact on the ground:

There is a national open school which gives girls and boys a second chance to appear for their exams, but it’s expensive. And their exam centers are usually in the cities. So, it’s kind of not an option for our girls, right? If you have five exams to write, you’re not going to tell your family, see you after one week, I need to go write my exams, right? So, what we’ve tried to do is work with the state governments to say, let us help you build out this policy which gives girls access to writing these exams. It’s worked in some states. Some states already had it, but it’s kind of defunct, so we’re working with them to make it accessible, make it free for girls so that fees are not a barrier for them. So, Rajasthan, for example, is free. So, in Rajasthan, two-thirds of the students writing the exams are girls. Whereas in the national open school where it’s paid, only 20% are girls…

More power to Educate Girls and their inspiring mission!

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash