AI: Why Fear Should Not Be Your Reaction

I enjoyed writing this LinkedIn post last week on words that you are most likely to come across in newspaper headlines only!

Btw, ALL posts are 100% written by me, (sometimes with some research inputs from AI).

The videos have been a little slower. You can expect one next week for sure.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Welcome to the one hundred and fifty-fifth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

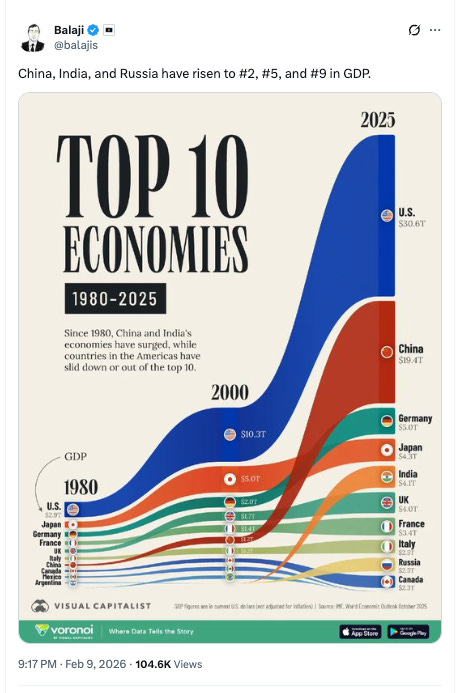

Lovely graph showing the relative change in shares of global GDP across major economies.

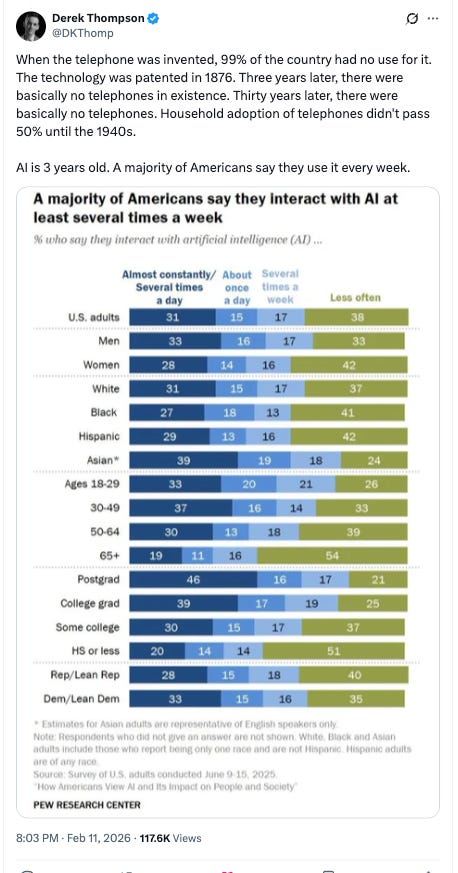

This is a powerful response by Thompson to an AI-sceptic. Loved the use of norm-variance and historical reference to make his strong point.

Hahaha, hilarious

For non-Indians who don’t get the reference: Indian mathematician Aryabhatta (or Brahmagupta) is credited with the first use of zero.

And, in every fuel pump in India, the attendant will point to the meter to indicate that he is, indeed, starting it from zero (and not from a higher number, trying to make a quick buck).

📄 2 Articles of the week

Arnav Gupta builds AI data centers at Meta and has a ringisde view of some of the core action.

In this piece he says that we need to be worried about the medium term impact of AI (not short or long term):

Will AI take our jobs?

Short answer:

Short term: not worried. because physics, and organisational inertia.

Long term: not worried either, because economic realities and faith in humanity.

Medium term: I am shit scared. We are ngmi.

Gupta believes that building physical data centres will be a short term bottleneck:

Because software moves fast, reality has to scale walls of physics.

- The strongest models today were literally trained on GPU generations and cluster scales that did not exist in 2020 (Deloitte).

- They run in data centers that had to be financed, built, cooled, and connected to a strained grid (CSIS).

- Power is now such a bottleneck that even shuttered nuclear capacity is being brought back for AI-era demand (e.g. Three Mile Island Unit 1 restart plan for Microsoft-linked demand) (AP).

Scaling from GPT-3 era toys to GPT-5.x era production agents is not just a model story. It is a semiconductors + grid + capex + regulation story. In other words: physics.

In the long term, humans will invent activity to replace current jobs:

Long term: we will invent work, because capitalism needs customers

I am much less worried about the long term, and not because I am naive. Because I have seen humans.

Humans are unbelievably good at inventing activity, attaching status to that activity, building a market around it, and then calling it “career growth.”

Consider some of the jobs that exist today that would have been unfathomable to a medeival guy:

If you explained “SEO specialist”, “product manager”, “actuary”, “growth marketer”, or “developer relations engineer” to a medieval peasant, he would assume you were either joking or collecting taxes in a new way.

He would be wrong. We invented those jobs. We staffed those jobs. We made PowerPoints about those jobs.

He then talks about the medium-term risk:

So medium-term risk is not “autopilot plus legal signoff.”

It is managerial span explosion.

One experienced human + many machine workers = fewer entry seats for humans.

India: when the seat-selling model gets kneecapped

Especially in India, where a lot of mid-tier white collar jobs are at risk:

If clients stop paying for seats and start paying for output, everything changes:

- junior hiring gets cut,

- margins get squeezed,

- top AI-native talent captures outsized upside,

- and the urban consumption flywheel takes second/third-order hits.

And that second/third-order part is the real fear.

For our sake, hopefully, we will figure out and adapt before the AI-pocalypse strikes!

This is a fascinating story of a life saved because of Tesla’s FSD (Full Self Drive) mode.

Here’s what happened:

On November 15, 2025, my father left Atlanta heading to Birmingham on I-20 West to help care for my grandmother. He had just received the FSD v14.1.3 update on his 2026 Model Y Launch Edition and it turns out this was the perfect version for this drive.

Around 3:50 AM, my phone rang. It was my dad. He was experiencing severe chest pain, could barely stay conscious, and could no longer safely control the vehicle.

they figured out the nearest hospital and then—this is the crazy part—remotely rerouted the car there:

My grandfather contacted my uncle in Douglasville, GA, who told us about Tanner Medical Center in Carrollton, not far from my dad’s location on I-20. I immediately pulled it up on Google Maps and shared the destination to his Tesla through the app. As an authorized driver on his account, I was able to remotely change his Juniper’s FSD navigation – all from my 2014 Model S (openpilot equipped).

The patient reached the hospital (which had been informed) and was saved. But had the FSD option not been there, he may not have made it:

He was diagnosed with a massive STEMI heart attack. Three arteries required immediate intervention. The doctors later told us that if he had pulled over and waited for an ambulance, or tried to continue to Birmingham, he would not have made it.

Crazy how technology can make such a difference.

📄 1 long-form read of the week

a. ‘AI isn’t coming for your future. Fear is’ by Connor Boyack

Connor is the President of Libertas, a Utah-based think-tank.

In this article, he uses historical references and a powerful idea from a French economist to make an impassioned plea to his readers: don’t let fear rule your response to AI.

Boyack starts with the key idea from the French economist:

“There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.” —Frédéric Bastiat, 1850

This single idea, written over 175 years ago, is the master key to understanding every AI doomer headline you’ve ever read.

He then relates it to the AI revolution:

When a new technology arrives, certain effects are immediately visible. You can see the assembly-line worker whose job has just been automated. You can see the copywriter watching Grok produce in seconds what used to take her hours. You can see the customer service team being replaced by a chatbot built with Claude Code in a matter of minutes.

This is “the seen.” It’s tangible. It’s emotional. It has a human face. And it makes for incredible content, because fear and loss are among the most powerful drivers of engagement.

Here are the unseen effects of AI:

But there is a second category of effects… the ones Bastiat said “emerge only subsequently.” These are the unseen. The new industries that don’t exist yet. The businesses that become possible only because costs have dropped. The creative work that gets unlocked when drudgery disappears. The entrepreneur who can now build alone what used to require a team of twenty.

We intuitively think of jobs as a fixed resource:

When you read a headline that says “AI will replace 40% of jobs,” your brain does something very specific: it imagines 40% of current workers losing their current jobs and sitting idle. It does not (it cannot) simultaneously imagine the new roles, new industries, and new forms of value that will be created. Because those things don’t exist yet. They’re unseen.

We have seen (some version of) this movie before:

When ATMs arrived in the 1970s, everyone was sure bank tellers were finished. A 1973 article predicted they’d eliminate up to 75% of tellers. London bank tellers were reportedly so panicked they snuck out and covered ATM keyboards with honey. What actually happened? Between 1985 and 2002, the US went from 60,000 ATMs to 352,000… and teller employment grew from 485,000 to 527,000. ATMs made branches cheaper to run, so banks opened more branches, and shifted tellers into higher-value relationship roles. The technology created more human jobs.

Boyack contrasts between the fixed pie delusion…:

So why do smart people keep getting this wrong?

Because of the fixed-pie delusion—the deeply ingrained, almost instinctual belief that the economy is a zero-sum game. That there is a fixed amount of work to be done, and if a machine does more of it, humans must do less.

… and a ‘garden’ analogy:

The economy is not a pie. It’s a garden. And technology is rain.

The automobile took away horse-cart drivers’ jobs… but look at what it created:

When the automobile arrived, the “pie” wasn’t horse transportation. It expanded to include suburbs, highway systems, motels, fast food, drive-in theaters, road trips as a cultural phenomenon, auto insurance, gas stations, auto repair, car washes, and an entire civilization organized around personal mobility.

What would it take to succeed in the AI age? Curiosity, experimentation and humility:

The learning curve is gentler than any previous technology shift in history. You don’t need to be a programmer. You don’t need an engineering degree. You need curiosity, a willingness to experiment, and the humility to let a machine handle the parts of your work that it does better than you.

The people who will struggle aren’t the ones whose jobs change. It’s the ones who refuse to change with them. Like the modern-day hand knitters, insisting that the old way is the only way, while the future assembles itself around them.

The internet was also a major breakthrough technology that disrupted several jobs:

The pessimists in 1995 could see the bookstore closing. They couldn’t see Shopify, YouTube, Stripe, the entire creator economy, remote work as a lifestyle, or the fact that a teenager with a laptop could build a global business from a bedroom.

Boyack ends with some great inputs on what people CAN do to take agency in the AI age. One point I particularly liked was this one:

4) Invest in what AI can’t do.

AI is phenomenal at generating, summarizing, analyzing, and pattern-matching. It is not good (yet) at: original judgment, deep relationship building, physical-world problem solving, moral reasoning, cultural intuition, or leading people through ambiguity.

Double down on those skills. They become more valuable as AI handles everything else.

He ends with a strong call to action (and some rhetorical flourish!):

The knitting machine didn’t ruin England. It made it the wealthiest nation on earth.

The power loom didn’t destroy the textile industry. It expanded it beyond anyone’s imagination.

The computer didn’t end employment. It created the modern economy.

AI won’t shrink your future if you refuse to let fear shrink your vision.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash