A Surgeon-Storyteller Shares his Secrets

A recent Wall Street Journal article about the rising importance of ‘storytellers’ become very popular. But it frames the issue very narrowly.

In this short deck (post on LI), I break down the implications from the article and how leaders should be desperately seeking to enhance their own storytelling skill.

This week’s video was about how you need to BLUF at work – that too to seniors! (I’m sure you know what that means, if you’ve read the book!).

And now, on to the newsletter.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Welcome to the one hundred and forty-eighth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

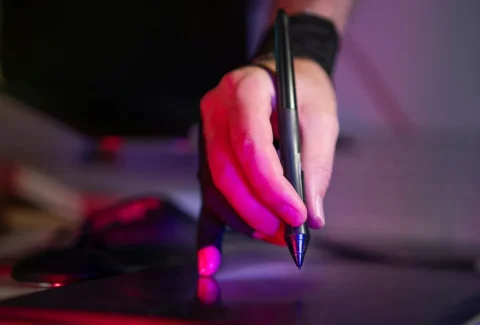

A picture is worth a thousand words. Peuyo is that rare storyteller who has a strong skill with words and visuals.

Whoa, that’s some ambitious framing. But yes, this does look like a historic milestone in the healthcare world.

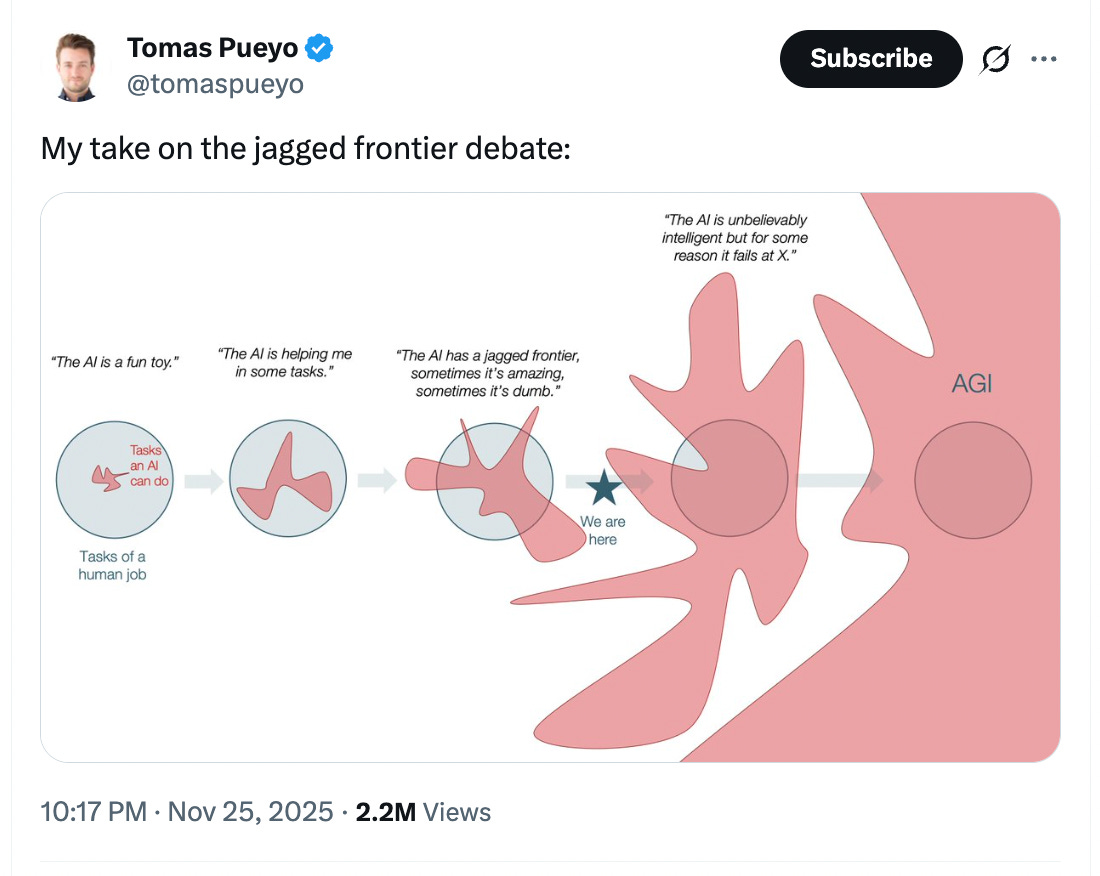

I’m guessing Spain is just one example, but this would apply to other Western countries like Greece, Italy, France…? Generous state pensions for the elderly may seem like a strong social good, but they do come with costs…

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘The Shape of AI: Jaggedness, Bottlenecks and Salients’ by Ethan Mollick

AI expert and author Ethan Mollick writes about how Nano Banana Pro is a big deal in the evolution of AI tools.

He starts with describing the ‘jagged frontier’:

Back in the ancient AI days of 2023, my co-authors and I invented a term to describe the weird ability of AI to do some work incredibly well and other work incredibly badly in ways that didn’t map very well to our human intuition of the difficulty of the task. We called this the “Jagged Frontier” of AI ability, and it remains a key feature of AI and an endless source of confusion. How can an AI be superhuman at differential medical diagnosis or good at very hard math (yes, they are really good at math now, famously outside the frontier until recently) and yet still be bad at relatively simple visual puzzles or running a vending machine?

(Note: Substack has changed the formatting of the block quote. I liked the previous version, with a dark line to the left. Not a fan of the current one, with parallel horizonal lines, which makes it confusing as to which is the ‘quote’ part… Anyway, in my newsletter, the italics is the quoted part.)

He then refers to Tomas Peuyo’s visual conception of the frontier (see tweet 1 above) and shares a different opinion:

While the future is always uncertain, I think this conception misses out on a few critical aspects about the nature of work and technology. First, the frontier is very jagged indeed, and it might be that, because of this jaggedness, we get supersmart AIs which never quite fully overlap with human tasks. For example, a major source of jaggedness is that LLMs do not remember new tasks and learn from them in a permanent way.

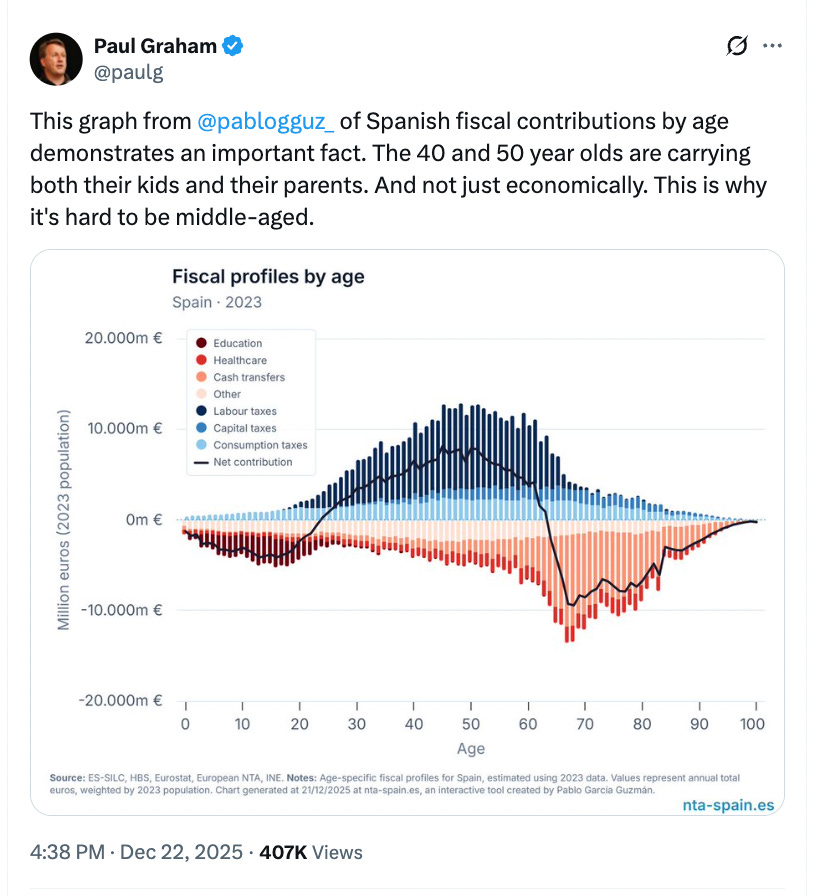

I loved the visualisation of the various bottlenecks to AI adoption:

The bottleneck migrates from intelligence to institutions, and institutions move at institution speed.

He makes a compelling point around ‘reverse salients’:

This is the pattern: jaggedness creates bottlenecks, and bottlenecks mean that even very smart AI cannot easily substitute for humans. At least not yet. This is likely good in some ways (preventing rapid job loss) but frustrating in others (making it hard to speed up scientific research as much as we might hope). Bottlenecks also concentrate the work of AI companies into making the AI better at things that are holding it back, the way math ability rapidly improved once it became an obvious barrier. The historian Thomas Hughes had a term for this. Studying how electrical systems developed, he noticed that progress often stalled on a single technical or social problem. He called these “reverse salients” – the one technical or social problem holding back the system from leaping ahead.

Mollick believes that Nano Banana Pro is a good indication of making progress on a reverse salient—image generation:

Bottlenecks can create the impression that AI will never be able to do something, when, in reality, progress is held back by a single jagged weakness. When that weakness becomes a reverse salient, and AI labs suddenly fix the problem, the entire system can jump forward.

The most powerful example of this from the last month is Google’s new image generation AI, Nano Banana Pro (yes, AI companies are still bad at naming things). It combines two advances: a very good image creation model and a very smart AI that can help direct the model, looking up information as needed.

I need to work on NBP and compare it with Gamma. Will share findings in a later post.

b. ‘I think India can do it’ by Noah Smith

Blogger and India-watcher Noah Smith presents the bull case on whether India will achieve its goal of becoming a developed country.

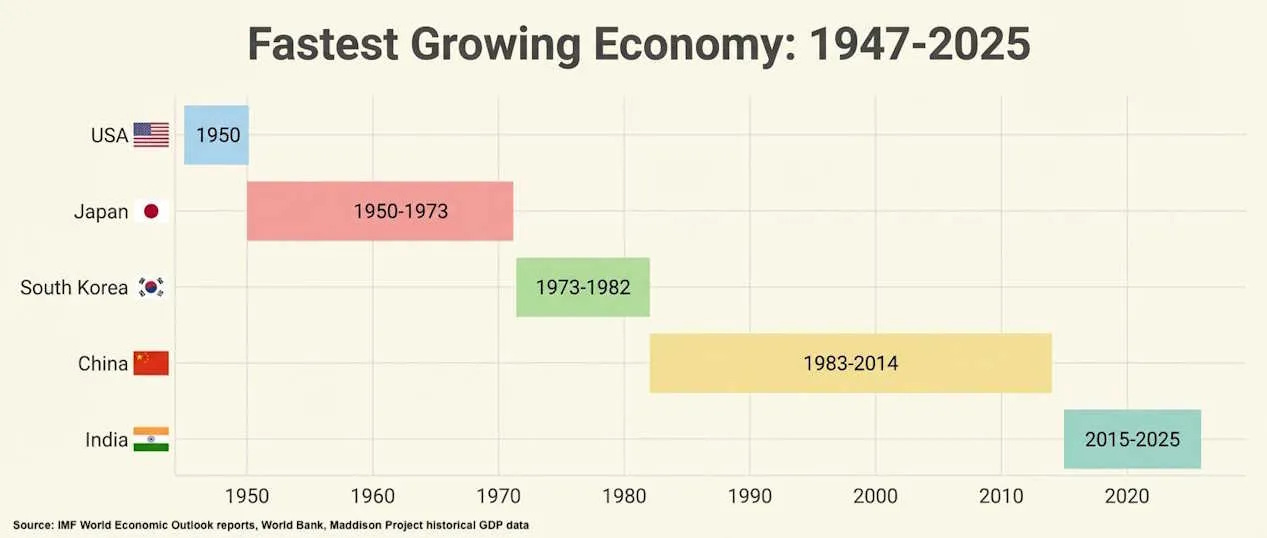

He starts off with an interesting chart that widens the historical frame on the question of “which has been the world’s fastest growing major economy”

In 2004, The Economist predicted that India’s economic growth rate would overtake China’s in two decades. In 2010, in an article called “India’s surprising growth miracle”, they shortened that timeline dramatically, declaring that India might overtake China in terms of GDP growth as early as “2013, if not before”.

In the end, it took two years longer. Since 2015, India has been the world’s fastest-growing major economy, taking the crown from China:

Bad news: We are still not growing at the pace China and S Korea did during their heydays. Good news: these growth rates are still transformational

That sort of growth rate is less than South Korea or China managed during their heydays of industrialization. From 1991 to 2013, China’s per capita GDP (PPP) grew at an annualized rate of 9.4%. But 7.2% would still be enough to utterly transform India in just a short space of time.

Noah does the math on the growth rate:

Two decades of 7.2% growth would bring India to $48,609 — about as rich as Hungary or Portugal today.

In other words, if India keeps growing as fast as it’s growing right now, it will be a developed country before kids born today are out of college.

To those criticising that it’s tough to keep up such growth rates for decades, Noah says that it’s been done before:

Yes, it’s likely that India, like China, and like every other rapidly industrializing country, will experience a slowdown in growth as it gets richer. But growth could also accelerate for a while. China’s growth slowed in the 1990s, but then accelerated in the 2000s after it joined the WTO.

He makes an interesting point—growth creates the need for more growth, as people get used to the idea of rising living standards:

There’s a theory out there, espoused by A.O. Hirschman back in the 1950s, that economic development creates political support for further development. Once the people of a country realize that rapid economic growth is possible, they may get used to the idea of their living standards increasing noticeably every year. On top of that, many elites become invested in the institutions of growth — owning construction companies, banks, and so on — and thus it’s in their interest for growth to continue

He then talks about promising trends in manufacturing growth and exports.

He finally tackles some common doubts about India’s growth story.

Overall the piece seems driven by opinions and a strong point of view, but a lot of the data points were eye opening for me.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

In my first job, I was gifted a book called ‘Complications’ (by my boss, Monika Sood). I was mind-blown. How could a surgeon write so well? He was telling complex medical stories in a clear, engaging and vivid manner. I became a fan and later gifted the book to several others in our healthcare consulting practice (and to clients).

Here’s how David Perell introduces him: “Dr. Atul Gawande has written four books and countless articles for the New Yorker. When you think about doctors who write well, he’s going to be the first person who comes to mind. What’s unique about him is that this isn’t something that came naturally to him. The work of research, writing, editing, shaping sentences, telling stories. Those are all things that he taught himself.”

Here are some extracts from the conversation:

I love this advice: Experiment a lot before 40, focus a lot after 40:

a friend of mine said that the advice he often gives is and I realize this is what I’ve done all my whole life. “Say yes to everything before you’re 40 and say no to everything after you’re 40”. So by that he meant before you’re 40, you don’t know what you’re good at. You don’t know what you’re energized by and the world is changing. Like when I graduated from college there wasn’t you know … the internet wasn’t a thing… So, trying lots of things that you know you’re curious about or potentially interested in allows you to figure out if you pay attention, “oh here’s what you know the parts of it I’m energized by here are the parts of it that exhaust me” and and… then just maximize for your energy and that’s what I was doing.

Dr. Gawande did 22 rewrites for his first New Yorker piece!

My friend, Jake Weissberg would tell me, “All right, this is what you’re doing well. This is what you’re not doing well.” He was being an editor. And so (he) would say, you know, do more of the first, do less of the second, and then he’d hand it back to me and I’d say, ‘what’s this for?’ He said, ‘you know, to rewrite’. I’d never rewritten a thing in college. Like I’d never heard of it. Like who rewrites anything? And that’s, you know, was the opening into, you know, when I got a couple years later a chance to write for The New Yorker, that was 22 rewrites. And, you know, I had… build up some tolerance for the process. For the first New Yorker piece, about 4,000 words was had 22 back and forths, five complete rewrites. I thought it would be a couple (of) months thing. It ended up being nine months, but, you know, it just kept getting better.

It’s crazy how Dr. Gawande found the time to do this. Imagine him in surgical scrubs, poring over a research paper for a piece due in a few weeks… The principle seems to be “If the activity gives you energy, you will find a way to get it done”:

… it was just as as simple as the basic principle I followed is if it gives me energy I want to do more of it and if it exhausts me I do less of it and the writing gave me energy and surgery does and some of the research stuff I did and so I just kept moving each ball a little bit forward along the way I had you know.

I wasn’t trying to write insane amounts… I set a goal of 30 hours a month… an average of an hour a day that felt doable…. there high variance in high variance, right? So… getting an initial draft down on paper would be just whatever time I could grab to do some basic research. You know, I in in those days there was a lot of turnover time in the operating room… like you could wait an hour, hour and a half between cases sometimes and and so I could get a slug of just reading stuff… get some weekend time and put a few hours into just getting it down and you know those initial days was writing an 800-word piece for Slate, my first piece for The New Yorker I was doing like one or two a year for the first couple years… and as I was getting to to the end of my surgical training and then I had more more control over my time and as I entered into practice I started reserving time for it.

How does a surgeon write in the New Yorker style—one, he writes naturally, and two, he has read a lot of the magazine and perhaps subconsciously imbibed its style:

I always felt like I was simply using my voice and I didn’t feel like I was needing to… I think I either just had read so much New Yorker that I had embedded… but you know trying to be very crisp, very clear, not really long sentences, be as vivid visual as I can, but also it’s all about the argument how I’m how you know do I have a sound case I’m making and a story I’m telling that illuminates that case. So, you know the editors definitely and my editor there Henry Finder who’s amazing you know is definitely sort of raised me and coached me in my writing. So I’m sure I imbibed a lot of the way that that they write.

Gawande talks about how openings are important in writing, and he would try to make it engaging and unpredictable for the reader. I also loved the idea of ‘O’-shaped and ‘W’-shaped stories:

The thing is we also have a bias not only for not boring, but also for not predictable. And if you read, you know, in a book I write, every chapter opening with a, ‘he was in the emergency room’ and, … that you’re just going to notice the mechanics at work. And so sometimes you start with a surprising idea. Sometimes you start with setting a scene. And I had to learn that, you know, it took a lot a lot of time. My editor would talk about like he’d literally talk about, you know, this this one is an O, meaning where it is starting is where it ends. It’s going to start where it ends. And… this one’s more like a W. We got three peaks and we’re going to work our way through and we’re going to advance from left to right.

Fascinating conversation with a fascinating guy.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash