Changing Your Story to Change Your Life

Finally the book is available for pre-orders (with some attractive bonuses!). Have you pre-ordered it yet? 🙂

This week I went to a place near Aurangabad for delivering a two-day storytelling workshop with a fun group of finance leaders (not an oxymoron!).

It was nice to revisit the city from where I completed my schooling. I got a shock when the hosts took me to a craft brewery for dinner. Impressed with the city’s growth!

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Welcome to the one hundred and thirtieth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

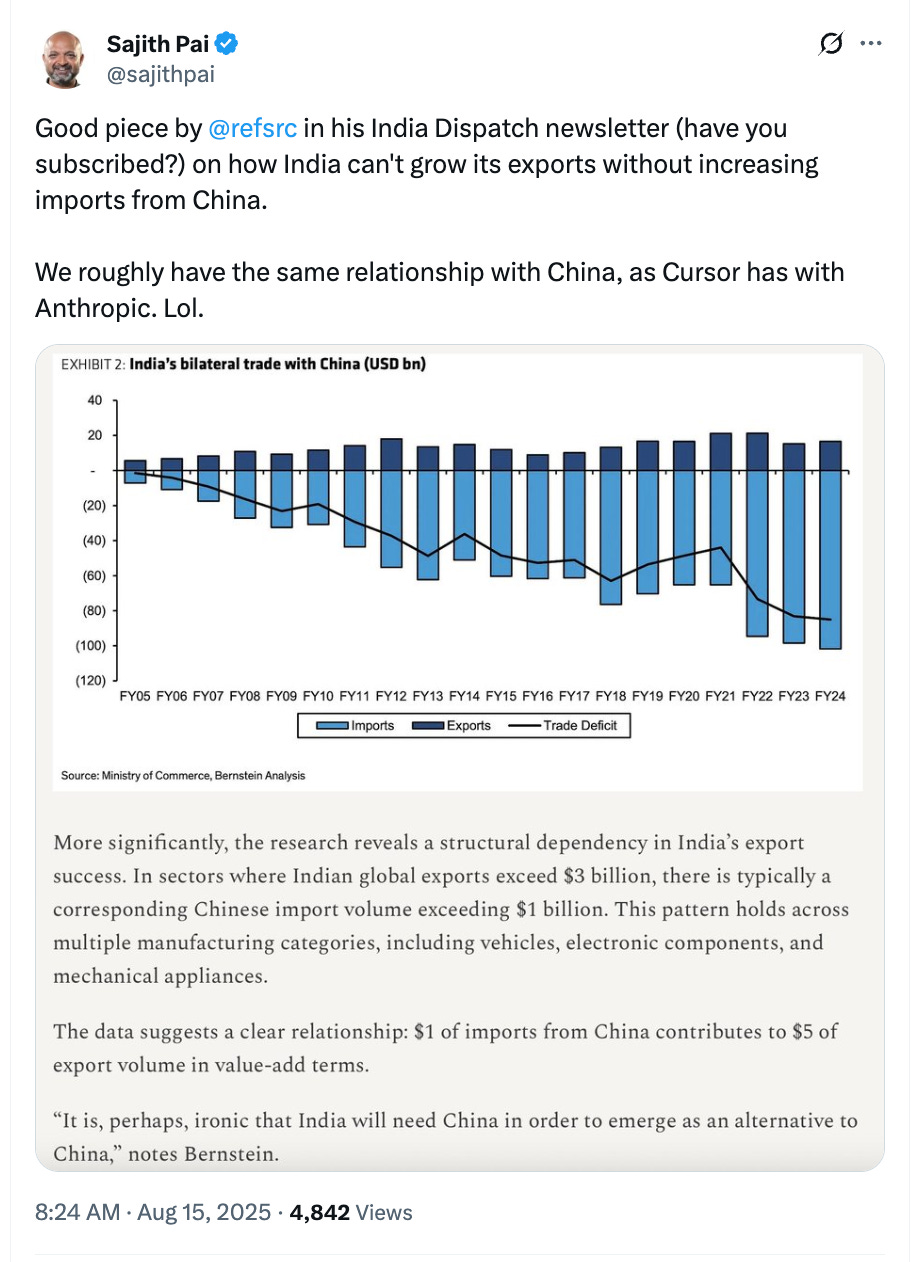

Fascinating relationship.

Global companies are asked to craft their ‘China + 1’ strategy. In manufacturing we seem to be following the ‘China+Value Add’ strategy.

Maharashtra, especially Pune, has had an outsized impact on Indic studies. Any historical reasons why…?

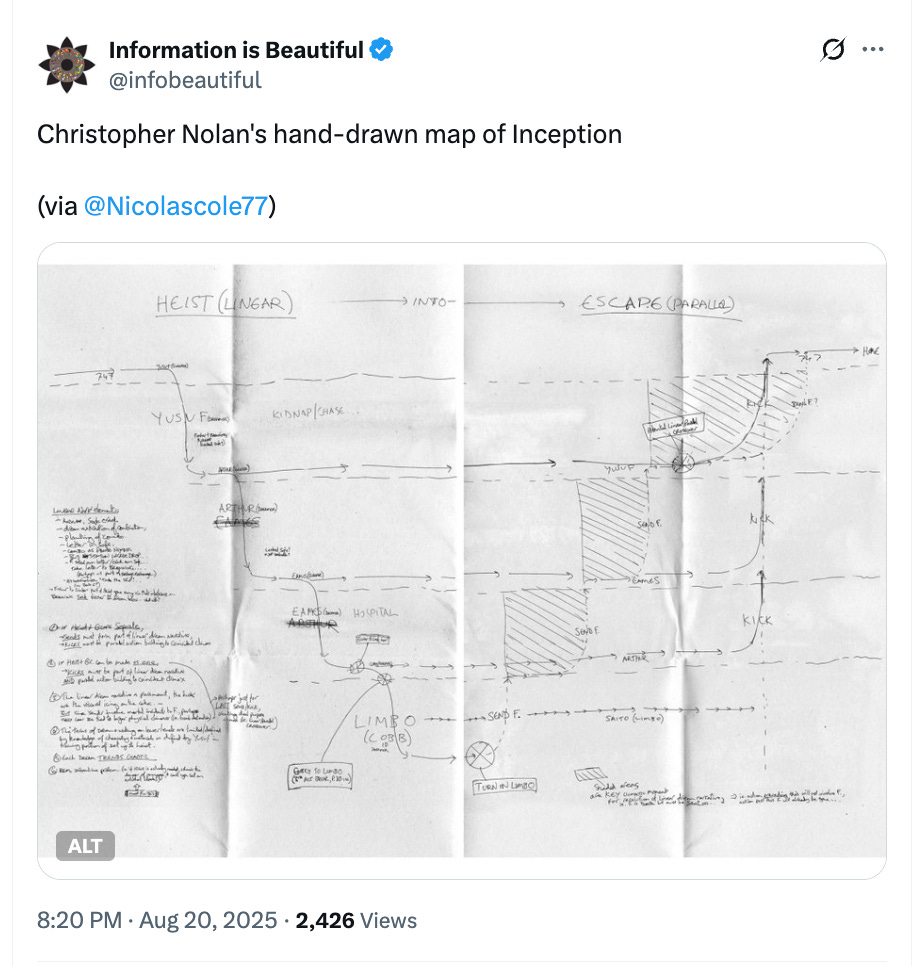

Not sure if this is authentic. But gosh, I’m struggling to even understand this despite having watched the movie (twice)!

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘Exotic Metrics: a Parable for Product People’ by Shreyas Doshi

You might have heard of Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

(For instance, hospitals striving to reduce the average length of stay of patients may end up discharging them prematurely, leading to increased emergency readmissions; or salespeople incentivised by units, may focus on selling low-priced high-volume products at the cost of higher-value options)

Most leaders are aware of this law, and would try to avoid it’s repercussions. That can be a problem, argues Shreyas in this superbly written article. He believes that in order to prevent ‘metric-gaming’, leaders end up unnecessarily complicating metrics:

Exotic Metrics make us feel smart, but if you really zoom out and are honest to yourself, it makes us act pretty stupid. It is highly contagious and chronic.

He explains this with an imaginary (but highly concrete) example:

Say you are working on a product that helps startups.

Maybe it helps them with their financial operations, maybe it helps them set up & manage bank accounts more easily, maybe it helps them hire high quality offshore engineering talent, or something else like that.

You now need to define a metric to measure your success / impact / progress towards your mission. Say you come up with this metric: Number of startups that are actively using our product.

The metric goes for review to your boss, Bob, who is worried about gaming:

Bob, genuinely wanting to help, says: This is a fine metric, but I am concerned it can be gamed. You see, the definition of a “startup” can be very vague. What if you / Sales just sign up a bunch of solo practitioners who are not really a startup. You could inflate this number quite a lot, hit the OKR out of the park, and still miss the spirit of our mission.

Bob sounds smart. Bob sounds genuine. And you certainly don’t want to come across as someone who’d game the system.

So you come up with a revised metric: Number of venture-backed startups who are using our solution.

The story goes on with different leaders adding different layers of complexity to the metric… and it’s not a happy ending:

Of course, what follows after this should also be painfully obvious, because we’ve all seen some versions of this play out (even if we haven’t had the courage to accept it):

– This metric is very difficult to calculate

– So dozens of assumptions have to be made in its calculations

– Which in turn reduces the accuracy of the metric

– This metric is very difficult to move in the near-term

– So targets get set somewhat randomly

– Some quarters, you drastically outperform

– You rejoice. You’re doing it right!

– You make sure everyone knows that.

– Some quarters, you underperform

– So you ask for more resources and x-fn alignment at the next QBR

– You created a fancy dashboard to track the metric

– But now no one looks at that dashboard

– Because everyone knows there will be nothing new to see, nothing insightful to conclude, nothing you can actually act on

– You keep setting new quarterly targets for the metric, but deep down no one on the team actually has any confidence that the projects you’re prioritizing will help hit those targets

What makes the piece so relatable is the super-concrete scenarios (including realistic dialogues) that Shreyas uses to bring the issue to life. Great example of storytelling.

b. ‘Writing is thinking’ from Nature Reviews Bioengineering

Writing is not just unloading the contents of our minds on paper. It’s the process by which we make sense of those contents:

… writing is not only about reporting results; it also provides a tool to uncover new thoughts and ideas. Writing compels us to think — not in the chaotic, non-linear way our minds typically wander, but in a structured, intentional manner.

The authors endorse the use of LLMs in writing, citing three advantages…:

- LLMs can aid in improving readability and grammar, which might be particularly useful to those for which English is not their first language.

- LLMs might also be valuable for searching and summarizing diverse scientific literature6, and they can provide bullet points and assist in the brainstorming of ideas.

- In addition, LLMs can be beneficial in overcoming writer’s block, provide alternative explanations for findings or identify connections between seemingly unrelated subjects, thereby sparking new ideas.

But ultimately, the core writing part has to be done by us:

… outsourcing the entire writing process to LLMs may deprive us of the opportunity to reflect on our field and engage in the creative, essential task of shaping research findings into a compelling narrative — a skill that is certainly important beyond scholarly writing and publishing.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘You 2.0: Change Your Story, Change Your Life’ on the Hidden Brain podcast

In this episode, the host Shankar Vedantam interviews psychologist Jonathan Adler about the field of ‘narrative psychology’ – how do you tell the story of your life.

Here’s Adler describing narrative psychology and how the stories we tell ourselves help us make meaning of the events in our lives:

You can’t totally control the things that happened to you in your life, (but) you have some more say about how you make sense of it.

And it’s important to remember, we’re talking about stories here. So we know from research on memory that we’re not very good at recording the objective facts of our experience. For a long time, that frustrated cognitive scientists. But in more recent years, it’s become clear that our memory works like this for a good reason.If you think about why we have memory in the first place, it’s not so we can hold on to every single thing that’s happened to us in some heretical way. We have memories so that we can make sense of what’s happening to us right now, and anticipate what might happen next.

So if you walk by a cave and a bear jumps out, you don’t necessarily need to remember that cave and that bear. But you need to remember that dangerous things might hide in dark places.

So the slippery reconstructive nature of memory is a feature of the system, it’s not a bug. And stories are an amazing tool for holding onto the meaning of our past experiences. The objective facts of our lives are what they are. But the stories are about where we draw connections between things, where we parse the chapter breaks of our lives. And those are narrative acts, not historical acts. And the way we do that can have big implications for our wellbeing.

Psychologists have classified these stories into two broad categories – redemption and contamination sequences:

Jonathan Adler: So stories that we narrate as starting bad and ending good, we call that a redemption sequence. And stories that start good and end bad, we call that a contamination sequence.

Shankar Vedantam: I see. So a redemption sequence is in some ways something bad happens to you. But in some ways, you’re rising from the ashes, so redemption. And a contamination sequence is: things are going pretty well… But then something bad happens to you, and then everything is downhill from there. So one basically has an upward trajectory. The other one has a downward trajectory.

The key insight from this episode—we humans have power of framing a set of events in either a redemptive or a contaminating way. Adler shares the story of a participant from one of his earlier studies:

Briefly, this was a middle-aged man. He’s recounting the story of the first date that he went on with the woman that he ultimately goes on to marry. The facts of the story are they go out. When he brings her home, they’re standing on her front porch. He leans in for a kiss, and then her dad opens the front door and interrupts them.

In the version that this man narrated…, he frames the experience as a redemption sequence. He says, “It really brought us close right at the very start of our relationship, and we stayed that way ever since.”

So this embarrassing moment had given them something to laugh about on their second date, and maybe it accelerated their connection. But he might have narrated the exact same sequence of events by concluding that it was this stain on the beginning of their relationship that could have contaminated the relationship in a way that they moved on from, but never could erase.

Neither version is more accurate in the historical sense. These are narrative interpretations that take on different thematic arcs, redemption and contamination. But these different ways of narrating our lives have different implications for your wellbeing.

Stories that have us take agency of our lives make us feel better:

Shankar Vedantam: Jonathan has found that stories that give us a feeling that we are in charge of our own lives are linked to higher wellbeing.

Jonathan Adler: Agency is a theme in people’s stories. We assess it along a continuum: from being able to direct your life, and then down at the other end of the continuum, you’re batted around by the whims of fate. Again, these are themes and stories. No one is completely in control of their lives, so it’s the way you portray the main character in the story, i.e. you.

In conclusion, Adler makes a simple yet powerful point—you are not just the main character of your story, you are also the narrator:

But I think for a lot of people, just the awareness that you are not only the main character in your story, but also the narrator, and that the way you choose to tell the story of your life really matters. That can be an empowering insight.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash