More Morgan Housel writing tips

Welcome to the forty-fourth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

🐦 3 Tweets of the week

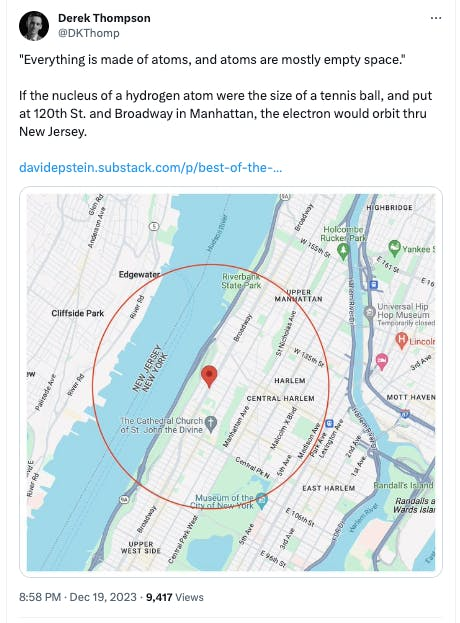

Superb example of making numbers relatable. From the book ‘The Universal Timekeepers: Reconstructing History Atom by Atom‘, by David Helfand.

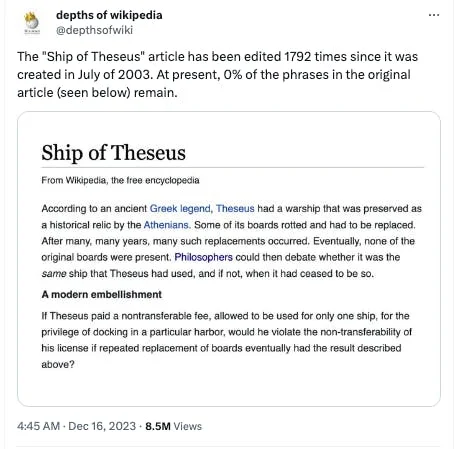

The Wikipedia article on the ‘Ship of Theseus’ just got ‘Ship of Theseus-ed’!

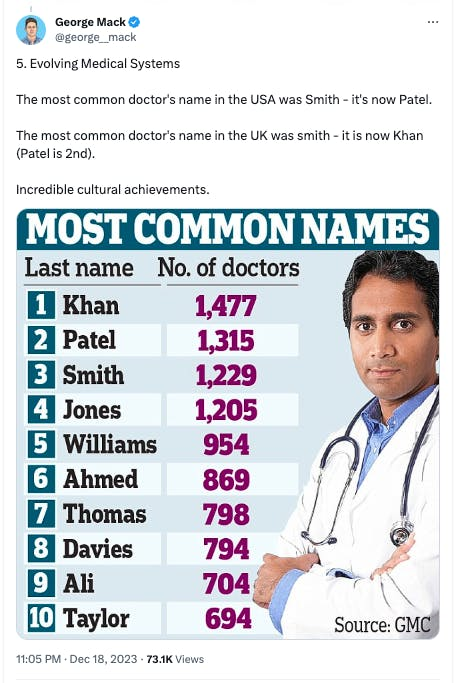

The pleas of thousands of South Asian parents to get their children to become doctors has borne fruit.

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘How Twitter broke the News’ by Nilay Patel

Twitter is a funny product. Many of its power users hate it, but cannot bring themselves to ignore it. In this long-form piece, Nilay rails against the several missteps taken by the platform, especially during the Elon Musk era.

Here’s some context on um, why the lack of context was what made Twitter so dangerous – and addictive:

The platform made newsrooms faster and more nimble, but it also made them more reactive and more afraid.

“Journalists are in general a bunch of insecure overachievers, so being in one ‘room’ with your ‘peers’ giving you constant feedback and information creates a truly awful petri dish in which the most terrible forms of groupthink thrive,” says (Lydia) Polgreen. “It can be very hard to resist for reporters, which makes it tough for editors to reorient their troops.”

But the context collapse that made Twitter so dangerous and so reductive was also what made it thrilling — your feed could contain everything from tech executives to Beyoncé fans to the president, and anyone’s tweets could be quote-tweeted and sent to viral heaven at any time, rocketing people into 15 minutes of deeply fucked-up fame.

This ability of Twitter to deliver so much fame to people seemingly at random gave it a lot of power… but so much power in the hands of so few people can be tricky:

Even a well-managed platform would have broken under the weight placed on Twitter — and Twitter has never been a well-managed platform. The notion that it could consistently deliver outsiders to power was itself outsized and short-lived. Eventually, the institutions pushed back. “I think it reached its apotheosis in the pandemic, in the Trump era, in the Black Lives Matter protests,” says Klein. “It reached a point of intensity that broke it because people had to reckon — all at once — with whether or not they wanted it to have that much power over other institutions, but also whether or not they felt like what it was doing was good for themselves and their institutions. And too many people decided no.’

That power might be fragmenting now:

“I’m on Threads and Bluesky, but part of me hopes none of the replacements ever really take off like Twitter did,” she (Lydia Polgreen) says. “I think a more fragmented social media landscape is probably healthier for journalism overall.”

That’s Smith’s view as well. “The big story of media now is fragmentation,” he tells me.

Fragmentation might be a good thing — it also means there’s an opportunity to try new, bigger, more interesting things, instead of trying to shove everything into the same box. “Twitter was built on the simple idea that our communication should be simpler and blunter, and over time, people really felt how much smaller that made them,” says Klein. “Somehow the scale of communication increased, while our ability to communicate decreased. I hope we are sensitive to that now.”

A decade of reporters working for Twitter’s algorithm while their bosses desperately tried to work for Facebook and Google did not result in stable business, happy reporters, or even satisfied audiences. Instead, the platform era hollowed out journalism, destroyed trust across the board, and resulted in a lot of shitty, boring work. It was a mistake — and like any good mistake, it was sometimes a lot of fun. But it’s over now, and there’s no one to blame but ourselves.

My take: Irrespective of all these doomsday scenarios, as a user, I just LOVE Twitter (or X, or whatever the name might be). It’s a fabulous way to learn from some of the best in whichever field you are in. And it can also be hugely entertaining. You just need to keep away from the trolls and the negative people (easy for me to say that though since I’m not in journalism or politics, or famous in any way!).

I wrote this LinkedIn post on the best books I read in 2023. I bought 29 books during the year but ended up reading only around 12 of them fully.

This post (and the accompanying document) shares some details about which books I enjoyed the most and why.

Happy reading!

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘How He Sold 4 Million Books’: Interview with Morgan Housel on the ‘How I Write’ Podcast

In an earlier newsletter edition (#38) I shared an interview of Morgan Housel by Tim Ferriss. This one features another interview – this time by writing coach, David Perell. While some points are similar, there’s a ton of new good stuff in this episode and I would highly recommend a listen.

(Morgan is doing the interview circuit to promote his new book, ‘Same as Ever‘)

Some interesting takeaways for me from the conversation:

Morgan did almost no reading or writing as a kid:

David: Did you read and write a lot as a kid?

Morgan: Virtually zero.

David: So when did that change?

Morgan: Well, I started as a writer for The Motley Fool out of desperation

Morgan doesn’t believe in the ‘shitty first drafts‘ principle, but instead ‘edits as he goes’:

David: How does that process (of editing) happen for you sitting at the computer? (Do) you just read it over and over and over?

Morgan: No, see, I almost do the opposite. I don’t know if this is the right thing to do. I don’t know if this is, this is probably not good advice. But, pretty much when I get to the bottom of the article, I just hit publish. And I don’t go back and read the whole thing again. But what I do do, is every sentence that I type, after I type it, I’m like, all right, is that good? Let me read it again. Is that good? Can I change this word? Oh, I might use, this is a better word here. So it’s like very, it’s just like editing as I go. Whereas I think, I think a lot of people will just like, let’s just smash out a bunch of words, and then we’ll go back and edit each line. Where I’m like, no, let’s just do every line as carefully as we can. So by the time you get to the bottom, you’re like, yep, okay, it’s good. We’re done here.

For Morgan, writing is a process of self-discovery – as in, he uses writing to think. Surprisingly, his 4-million copy bestseller initially just started off as a blog post title in his head:

Morgan: … when I start an article, I have no idea where it’s going to go. And a lot of times the reason I start it is because I’m like, I want to learn about this topic. So I think that’s actually pretty common. And a lot of people will think like, oh, this author wrote this book. And they imagine that the author had all of that information in their head. And then they just like regurgitated it on, onto the paper. (Instead it’s) the process of writing is what teaches you. And so all of, every one of these articles, when I start writing it, usually it starts with, it often starts with this, a title, a headline. I remember, having lunch with Patrick O’Shaughnessy in 2017. And he said, what are you working on? And I said, I want to write a blog post called ‘The Psychology of Money. And he kind of said, what’s it about? I’m like, I don’t, I don’t know, but that’d be a cool, that’d be a cool title, right? Like, it’s a catchy title. I think it’d be good. And so I had the title in my head, but I had no clue what was like, what am I going to fill it out with? Like, I don’t know. I’ll figure that out later, but that’s, that’s always how it works. And. And literally every single piece, when you start writing it, you have no idea where it’s going to go. And sometimes, where it ends up is like, sometimes the opposite of what you thought. Because you start learning about these topics and you’re like, oh, my thesis was this, but as I learned more, it turns out it’s actually the opposite. But the opposite’s pretty cool, so let’s write about that. So I think it’s always, um, it’s just a learning process for me.

Put extra effort into the first and (especially) the last sentences of your chapters:

David: Do you have a good way of thinking about conclusions?

Morgan: I think the most important part of any article is probably the first and the last sentence. The last sentence (especially). Because the first sentence hooks you in, the last sentence is how you… the last feeling you’re going to have with it. So I try to, I try to think about that quite a bit, uh, in there. Uh, the very last sentence in Psychology of Money is the title of the first chapter. So the title of the first chapter is No One’s Crazy, and the last sentence of Psychology of Money is No One’s Crazy. So that was intentional. I don’t know if anyone noticed that or if it had any impact, but that was, I think you should always put an excessive amount of thought, an abnormal amount of thought into the first and last lines.

David: Do you have any way of thinking about it, or is it just like a very intuitive sense? Like, there’s something there, right? Closing the circle where it began. I’m going to open it somewhere, I’m going to close it somewhere, and it’s… It’s going to be this circular…

Morgan: The worst that you could do, the absolute worst writing, is that your last sentence is, ‘In summary…’, like that’s, that’s, that’s when you know you’ve, you’ve, you’ve lost it. It should be some sort of emotional like, boom, just leaves right there. And it hits you at the end of like, that’s, that’s what it is.

Keep your chapters (and paragraphs) short:

David: I like this line that you have in, ‘Same as Ever’ right at the beginning. It’s ‘none of the chapters are long and you’re welcome for that’.

Morgan: Yeah, that’s how I feel as a reader. I’m kind of saying that back to like selfish writing. I’m saying that to myself. I don’t like long chapters. People like getting to the end of a chapter because it feels like they’re making progress. They’re kind of, it’s like in the video game. You’re like, oh, I beat the next level. The person who does this the best and who is just like shameless about, uh, short chapters is Eric Larson. Who’s written many, many books. His most recent famous one is um, ‘The Splendid and the Vile‘. ‘The Splendid and the Vile’ is about the London Blitz bombing. And some of his chapters are, are a paragraph. You know, in his average book he’ll only have like 150 chapters. But some of them, most of them are a page or two. And it’s just, it’s almost impossible to put the book down because you’re making so much progress. And the opposite of that for a lot of readers. You get to a chapter and you’re like, oh, let me see how, oh, this chapter is 40 pages. A lot of people would just be like, ah, you just feel like you have this giant burden in front of you to try to plow through. So if you can keep people going, keep them feeling on track, and keep them feeling like they’re, they’re winning the next chapter, that’s really important. And I think at the micro level of like how long your paragraph is, it’s kind of daunting when you see a page and it’s just a giant uninterrupted block of text. Whereas if you can really make it just like, just break up your sentences. It’s fine to have if every paragraph is two sentences, but you just keep people going. It’s a much easier way to read and it’s less daunting. And because it’s less daunting, you’re more likely to keep the person on the page rather than being like, I don’t have time for this. I got to go do something else.

This 2-hour conversation is a treasure trove of writing advice. Pick what appeals to you!

PS: I’m on vacation during the next week, so there will be no newsletter dated 30th December. We will resume from 6th January 2024. Wishing you a very happy new year!

Bonus: A response to the Peter Attia conversation on longevity

In an earlier newsletter, I had shared a podcast conversation with Dr. Peter Attia on the science of living longer and better lives.

To that email, I got a lovely response from Anand K, a good friend and co-founder of Envint (a sustainability, climate change, and ESG services firm). Here’s Anand’s response:

“Hi I saw Story Rules feature Peter Attia’s conversation on longevity! Although I didn’t listen to it, I did read his book recently and was quite impressed by the depth of research and explanation (though a bit repetitive at times).

My understanding of Ayurveda through personal experience has given me some insights – sharing a few.

- Ayurveda is literally the science of life and longevity

- There are three stages of health:

- Arogya – without disease

- Swasthya – healthy

- Sukha – where you make others feel better

- Ayurveda uses indicators that are quite integrative in nature, rather than specific like WBC count, etc. For example

- Quality of pulse and not pulse rate. This is gained thru experience from teachers

- Colour of eyes, tone of voice, etc. are also good indicators

- A consistent daily routine or dinacharya that includes balanced eating, working, and sleeping patterns can have tremendous long-term effects

- Emotional state of the person preparing the food has an impact on the person eating it

- Hence mass-produced food can never have the same impact on health as compared to home-cooked food made by a loved one

- I firmly believe both allopathy and ayurveda have their place

- Allopathy for issues like trauma, emergencies

- Ayurveda for well-being and longevity

In summary, Medicine 3.0 can look back and learn from our age-old Ayurvedic wisdom 🙂

Cheers, Anand”

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash