The Inside Story of India’s Eco Reforms

Last week I recorded two videos for my soon-to-be-launched YouTube channel (I do have some older videos on my existing channel, but they are very basic. The new ones would be recorded in a studio, with editing etc.)!

It was surprisingly nerve-wracking initially talking to a camera… but eventually I became comfortable and it felt at least a little bit natural.

When the video is up, I’ll let you know!

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Welcome to the one hundred and twenty-seventh edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

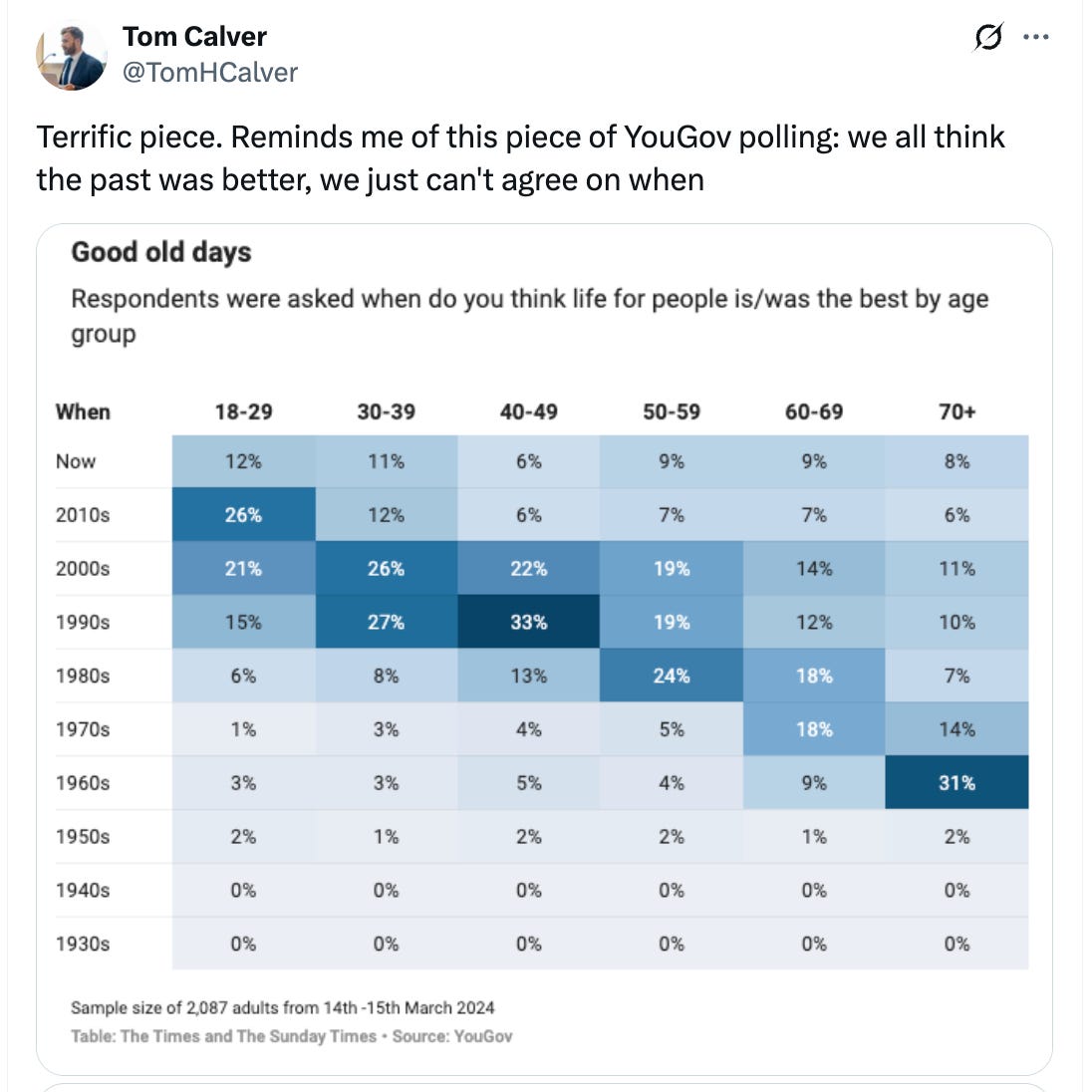

Hahaha, I might be an odd one out here… I think now is better!

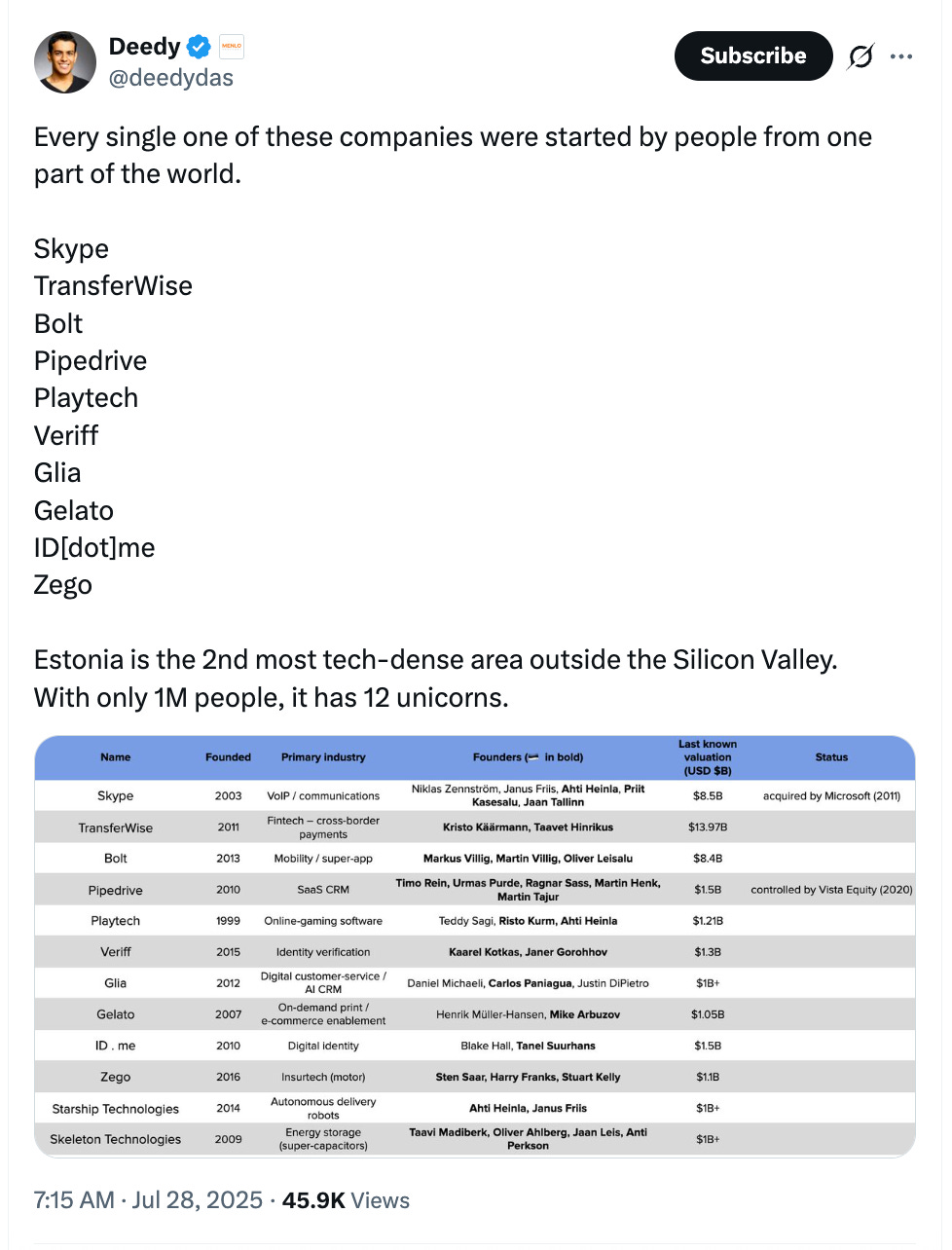

I didn’t know that Estonia (with a population of 1.4M—equal to a Faridabad or a Nasik) had such an outsized role in the world of tech startups!

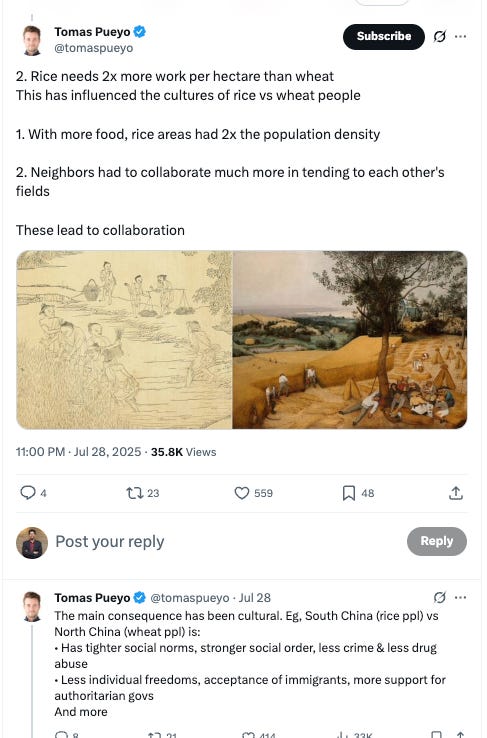

Fascinating thread on the impact of rice vs. wheat cultivation on society formation, co-operation, centralisation, governments etc.!

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘The US Economy Was Supposed to Be in a Recession By Now. What Happened?’ by Derek Thompson

This is an interesting article where Thompson tries to deduce why the US economy still seems to be doing well despite the unpredictable and widely criticised economic policies by Trump:

In his first months in office, President Donald Trump announced a set of tariffs that were immediately lambasted by economists and business leaders. Several experts predicted an imminent recession and higher inflation.

Despite dire predictions, the economy seems to be doing ok:

But now it’s July and the US economy seems … kind of fine? The Wall Street Journal offers a more complete diagnosis: “The stock market is reaching record highs. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index, which tumbled in April to its lowest reading in almost three years, has begun climbing again. Retail sales are up more than economists had forecast, and sky-high inflation hasn’t materialized—at least not yet.”

How to explain the contrast? One factor Derek says is that there was a lot of smoke and not enough fire in the policies:

Many of the tariffs that were announced were un-announced, or delayed, or never went into effect.

Two, tariffs are bad and poisonous, but it takes a lot to ‘kill’ the US economy:

Tariffs are bad. But they’re like a moderate amount of poison, and the US economy is very big and hard to kill.

Some economists estimate that it’s still bad – there’s a fair bit of unseen damage. I love how economist Jason Furman frames the effects here (emphasis mine):

“If you asked everyone in the country to come together and set fire to $1,000, that would seem like a phenomenally stupid idea, and for decades, you’d remember the president who came up with it,” the Harvard economist Jason Furman told me on my podcast Plain English. Economic growth in 2025 looks like it’s about 0.5 percentage points off from its pre-Trump trajectory dating back to late 2024. “Half a point off growth is about a thousand dollars per household,” Furman said.

Thompson concludes that despite the economy doing better than predicted, tariffs are not a good idea:

Ultimately, I think the most important reason why Trump’s tariffs haven’t brought down the economy yet isn’t that tariffs are good, but rather that so many economic actors—including businesses and the Fed—recognize that they’re bad that they’ve taken counter-measures to blunt the badness.

b. ‘Beyond Humanity’ by Santosh Desai

In this lovely, poetic piece, writer and branding expert Santosh Desai mulls about the implications of the rapid progress in AI.

Desai asks some fundamental questions—are machines just tools built by us, or the next stage in evolution?

…that humans are not the pinnacle of evolution, but a transitional species. A luminous midpoint. The awkward bridge from carbon to code. In this scenario, machines are not tools we built; they are the beings that emerged through us.

He then wonders—will the machines discard us or use us:

The difference between these two futures is not technological—it’s philosophical. In one, evolution discards us in favour of a better life form. In the other, evolotion chooses us as the host for its next leap.

Deep philosophical writing, in simple, evocative prose!

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

There is a lot of great material about the story behind India’s economic reforms. For instance, Vinay Sitapati’s excellent book, Half-Lion (the biography of P. V. Narasimha Rao), Amit Verma’s podcast interviews with various guests, and Shruti Rajagopalan’s resource website called The 1991 Project

This interview with Rakesh Mohan, one of the architects of that incredible period, is a superb addition to that list.

There were many fascinating (and diverse) tidbits for me from the conversation.

The reasons for the onerous Licence-Permit-Quota raj were the mindset of control that the British rulers bequeathed:

…when we started on this journey in the early 1950s with the first five-year plan, ’1951 to ’56, we had inherited a civil service system and system of administration which is essentially control-oriented because that was the job of the British colonizers. The whole system, obviously, they were not that much interested in development, if at all, but they had to control the very, very large country.

To some extent India’s embrace of a major role for the government was understandable because at that time the fastest-growing economy was the Soviet Union:

If you’re sitting in the ’50s, ’60s, what model did you have? The fastest-growing economies had been the socialist countries, including the Soviet Union. In that sense, you really have to think back, “What was it that we were reading? What was it that we were observing? What are the models available?” It is certainly true that the socialist economies grew fast at that time before they got sclerotic.

Even there, while the numbers were impressive and everything looked good from the outside, things were rotting from the inside:

Rajagopalan: My grandfather and his younger brother both were journalists. They’d go to Moscow on these press junkets or something. It’s tightly controlled. The government officials take you everywhere. They told me much later, well into the ’90s, they told me that in hindsight we should have figured it out. Because our friends in Moscow would ask us to bring soap, toothpaste, some really simple things that you can’t understand why they don’t have access to that. Now in hindsight, we completely understand the shortages were just pervasive across the board, even for the elites. We didn’t put it together because everything looked so good.

In 1991, Prime Minister Rao took up the powerful Industries Ministry himself—so that he could give up the power:

… because of all these controls and licensing, the minister of industry was a very powerful person politically and, of course, otherwise. It is unlikely in my view that had he been industry minister, that he would have agreed to give up all these powers because Narasimha Rao became the prime minister and he’d been the industry minister, this was much easier to do.

A major miss in the 1991 reforms was the de-reservation of industries from the small-scale industries list:

MOHAN: Apparel, footwear, many plastic items, cutlery. Basically, almost anything you use in the home. I think anything that you look around here would have been reserved for small-scale industries. One big omission and failure in the ’91 reforms was indeed that we couldn’t de-reserve or release those industries from those controls.

RAJAGOPALAN: But it did happen. That’s the good news. Eventually.

MOHAN: It happened 20 years later.

RAJAGOPALAN: Yes, much later.

MOHAN: One of the wrong things that was done was that whereas we liberalized imports over a period of time, lower and lower tariffs and removal of quantity controls, NTBs, and so on, what happened in those 20 years before they were released of de-reserved was that it was totally inconsistent in that we allowed, say, apparel to come in or toys to come in or shoes to come in and so on manufactured by large industries abroad, when we were not allowing our own large industry to produce those items, which doesn’t make any sense whatsoever.

RAJAGOPALAN: We just hobbled our own domestic industry.

A key worry for a lot of people is that, has India missed the export-bus? That while China and the East Asian economies grew on the back of exports to Western economies, the demand from the West is not likely to be what it was earlier.

Mohan and Rajagopalan disagree and argue that other regions will grow to generate that demand. There would be no shortage of demand:

MOHAN: …The second thing I would say is that the idea that in the last, say from early to mid-’90s to early mid-2010s, that the demand generator was the United States, which brought up all these countries, including China in particular, but now there wouldn’t be such demand. That’s again, false.

RAJAGOPALAN: I think it’s false.

MOHAN: The way I look at it is that if you take China plus South Asia as a whole, plus ASEAN, that’s more than 4 billion people.

RAJAGOPALAN: They’re getting richer.

MOHAN: They’re getting richer. Average income with a lot of variation is $4,000, $5,000 a year. Most projections, including for China today, suggests at least for next 10 years it will be 4%, 5% growth. Maybe below, who knows, because of demographic changes, et cetera. The point is that also incremental GDP growth as a share of global GDP growth, about two-thirds or so will come from this region. There’s no shortage of demand.

Plus, as China becomes richer, it may become expensive as a manufacturing destination. The question is, can India Exploit this demand or will it go to other countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and in Africa:

RAJAGOPALAN: No. There’s an additional thing, which is on the other side, China is getting richer, which means its people are going to do fewer of these jobs.

MOHAN: Of course, and they’ll be demand from there.

RAJAGOPALAN: Exactly. Those jobs are now going to Vietnam and other places. They’re even going to Africa, but they’re not coming to India. They went to Bangladesh before they came to India.

Towards the end, Mohan shares a fascinating anecdote from his college days and makes the point that maybe Indians just don’t like doing things with our hands:

When I was doing electrical engineering as undergraduate in London at Imperial College… there were 90 of us in the electrical engineering cohort in my class. At the end of the course or the degree, the last semester, that is summer semester, we had already done all the exams and stuff. We had to do a project, a graduating project. One of the things I always remember is, 90 students, I think there were only eight of us who are what I would call subcontinentals, that is people of Indian, Pakistani origin…

What is interesting was that when we had to do the project, almost everyone (else) did a physical project. Building some apparatus, engineering apparatus to do with electrical engineering, and then doing that, and showing it. Of us eight or so, everyone except for one did a software project. We just don’t like doing, even myself, just don’t like doing things with our hands. Somehow, there’s something from there which I can’t prove. I’m not a sociologist. There’s something there.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash