The most important person in banking

Welcome to the fifty-first edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

🐦 3 Tweets of the week

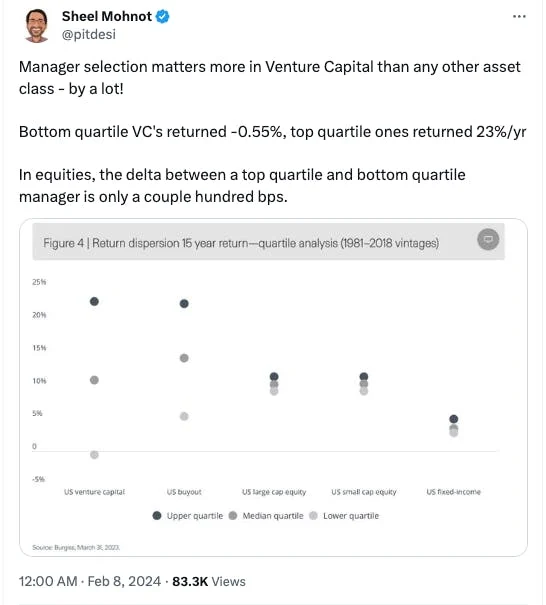

Such a fascinating stat – and great visualisation! (Data from this report)

Not just editing – this applies to writing too. There’s always the temptation to just ‘finish off’ the troublesome parts. A true craftsman irons out every crease though.

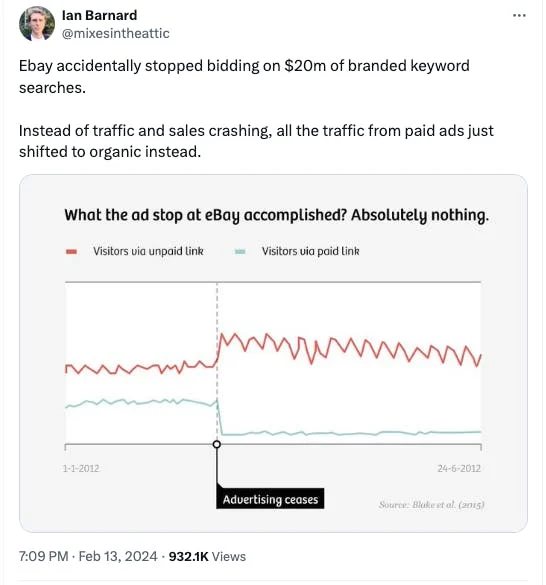

Never assume causality – always test with experiments, as I shared in my long-form essay on Causality in storytelling!

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘All My Thoughts After 40 Hours in the Vision Pro’ by Tim Urban

I know, I know. Everyone is raving about that Mark Zuckerberg video comparing the Meta product (Quest) with Apple’s Vision Pro. The video was … okay, I guess? I mean, instead of relying on impassioned speeches by company CEOs, one would need to actually try out both devices to know the difference.

Or, you could read (and watch) this fabulous piece by Tim (Urban, not Cook) on the Vision Pro. It’s a great ‘show-don’t-just-tell’ review.

Tim shares several cool features of the device. For example, it uses an interesting way to seem like it’s transparent and show your ‘eyes’ to others who look at you:

While it’s not perfect, it’s almost like you’re wearing a transparent snorkeling mask. The headset is in fact opaque – cameras on the outside transmit the world onto screens on the inside. But the screens are so good and the latency so low that it really seems transparent. Then there’s the much less successful attempt to make it look transparent from the outside as well, using cameras on the inside to broadcast your eyes onto the front of the headset. The goal is that if you’re talking to someone while wearing the headset, it feels to both people like you’re wearing a transparent snorkeling mask. But at least in V1, the eyes don’t show up nearly as well as advertised.

Another cool feature is eye-tracking:

Vision Pro’s eye tracking is outrageously good. It knows precisely where you’re looking. So all you do to select an app is look at it and tap your thumb and index finger together. Your hand doesn’t need to move up to do this, just somewhere the headset can see it. Watching the ads, it seemed like this might be annoying to do, but it’s every bit as easy and intuitive as opening an app on a smartphone.

And here’s Tim attempting to put this device in historical perspective:

It’s very crude right now, but it’s a primitive version of something we’ll probably all be doing constantly in the 2030s. It’s the next step in a centuries-long human mission to conquer long-distance. First there were letters, then phone calls, then mobile phones and video calls. The next step is VR hangouts.

Even if you can’t read the article, just watch this video by Tim taken while he is wearing it. It’s quite mindblowing.

b. ‘Sign-posting: How to reduce cognitive load for your reader’ by Wes Kao

Wes Kao (co-founder of online learning startup, Maven) wrote a neat little post on the importance of ‘sign-posting’ in writing:

Sign-posting is using keywords, phrases, or an overall structure in your writing to signal what the rest of your post is about. This helps your reader quickly get grounded, so their brain doesn’t waste cycles wondering where you’re taking them.

You can use sign-posting throughout your writing:

– Memo level: Headers, subheaders, toggles, paragraphs, white space

– Paragraph level: Topic sentences, bullet points, numbered lists

– Sentence level: Transition words or intentionally sequencing words in a sentence

Some of the examples cited are quite mundane. But overall the article is a useful reminder to keep your audience’s ease of comprehension in mind:

The main benefit of sign-posting is it makes your writing more skimmable—it makes longer writing feel shorter, clearer, faster-paced. This increases the chances your recipient will actually read your whole document and, more importantly, take action.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

This essay is an arresting portrait of banking colossus JP Morgan Chase and it’s long-time CEO, Jamie Dimon, the tallest leader in global banking.

This portion is such a vivid “Show don’t tell” description of Mr Dimon:

Jamie Dimon has an ego. His intelligence isn’t a bluff. He gets to the essential point quickly. He’s not afraid to have smart, talented people work for him. He’s not afraid of firing people working for him. He talks constantly about doing the “right thing.” He has a temper. He doesn’t suffer the unprepared. He demands written reports 48 hours ahead of time. He absorbs more from those reports than his executives think possible. He’s impatient. He likes — exalts in — single-sheet to-do lists.

Three of his grandparents immigrated from Greece. He grew up in Manhattan and Queens. His voice holds onto Manhattan and Queens. He didn’t get into his first choice of college. He got rejected from 14 of the 15 jobs he applied to after college. He can be funny even if his humor can come in repeated bits. His writing voice is blunt, loose, commanding. It does not feature what his speaking voice was long known for: a whirlwind of fucks. He’s a Democrat. He is patriotic and curious about policy. He doesn’t like black-tie affairs or golf. He has no conspicuous hobbies. He enjoys traveling for his job and a country place in Bedford. Otherwise, in the same penthouse on 93rd and Park that he bought when he moved back from Chicago, he is a homebody, preferring the company of his wife and their three grown daughters. He cares about the bank. He is interested in the bank — its position, its markets, its loans, its risks, its risks again, the point of view of people on the front lines and three rungs below him.

Risk aversion is a rare trait in Wall Street, but seems to typify JP Morgan’s approach:

Perhaps the core of JPMorgan’s differentiation is risk management. This starts with a “fortress balance sheet,” a phrase inherited from Dimon’s Citigroup days. At its most basic, the fortress is built with a decision to hold more capital in reserve than even the regulations require and to use clear-eyed accounting to not disguise hidden liabilities

This sounds like fun:

The retired executive told me that JPMorgan meetings could be “90 percent negative,” focused on what could go wrong, even regarding businesses where nothing was going wrong. He was not nostalgic for Sunday nights reading 60 pages of numbers. (“Not just reports,” he clarified. “Sixty pages of just numbers.”)

Fascinating rationale for why JP bought First Republic, a struggling small US bank that was under the threat of a bank run):

There was a defensive and offensive strategy for that bid. The defense-oriented reason, as explained to me by Ramsden, “is that JPMorgan was going to pay anyway and might as well get something out of it.” The FDIC insures bank deposits, but it’s not an insurance company. It’s a regulatory body that collects money from banks. After Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed early in 2023, the FDIC issued a special assessment of $16.3 billion. (It’s like if your neighbor burned down her house and, the next month, the fire department sent everyone else on the block a special bill.) In our two-tier regulatory system, the smallest 4,000 or so banks will pay nothing of this assessment. The largest 114 banks will pay it all. Per Ramsden, JPMorgan is usually responsible for about 15 percent of these assessments. The market expected a failure of First Republic to lead to another one for $25 billion to $30 billion. Had JPMorgan not bought First Republic, it would have had to pay 15 percent of that, and 15 percent of every assessment following, domino failure by domino failure. That’s reason enough for JPMorgan to end a bank panic.

Possibly no other person has made such a massive difference to the whole industry and economy:

JPMorgan was also not on a road to becoming the far-largest, most-respected bank 20 years ago. It achieved that position by being well run and gaining customers in the marketplace. It did so by being cautious and taking on less risk. The industry would be quite different today — quite possibly worse — had Jamie Dimon built something different by taking the job selling nails*.

* Before joining JP Morgan, Jamie Dimon was considering joining Home Depot as CEO.

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash