The Remarkable IPL Story

On the 5th of July, I got the first version of the typeset edition of my book. It was surreal… and a bit overwhelming. The book has come out to be much bigger than I expected!

Over the next few days, even as I was juggling training sessions and client calls, I went through the typeset manuscript and identified several changes and tweaks.

It is unnerving how one keeps finding errors and potential improvements in a text despite several rounds of editing.

At some point though, I will just have to let go… and send it to the printers. Will be a fulfilling, scary and bittersweet moment.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Welcome to the one hundred and twenty-fourth edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

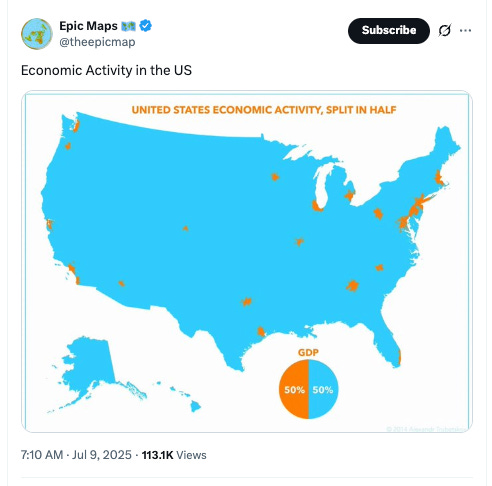

Striking visual on the concentration of economic activity in the US.

Isn’t this how economic activity is usually distributed in most countries? I am always bemused by policymakers’ efforts to ‘spread’ development evenly across geographies. Economic activity will be concentrated and people will migrate to where those opportunities are. I wish people have less of an emotional reaction to migration, especially when it is for better opportunities (and not distress migration)

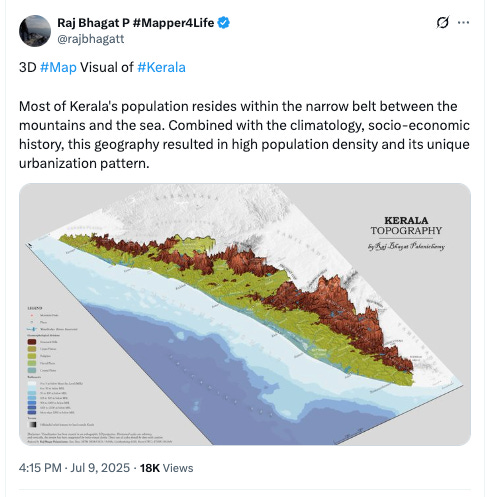

Beautiful 3D relief map of Kerala. Check out the Palakkad gap.

Hahaha, couldn’t resist sharing that dad-joke.

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘The Gujarati Kingdom That Almost Joined Pakistan’ by Sam Dalrymple

Sam is the son of the illustrious historian, William Dalrymple, and seems to be a talent to follow. (As the say, the acorn doesn’t fall too far away from the tree.)

In this fascinating article (with some gorgeous images), Sam shares the history and partition-era story of the kingdom of Junagadh.

This seems to be a hidden jewel in India:

The entire history of Gujarat seems to have played out here. There are Buddhist Caves over 2000 years old, ancient Hindu and Jain temples, early medieval stepwells, a preconquest mosque, and water gardens built by the Babi Nawabs.

I didn’t know that Junagadh had an Ashokan inscription:

But in 1838, James Princep (my ancestor!) deciphered the Brahmi script, and began to translate a series of inscriptions on a rock by the base of Junagadh’s Girnar Hill.

It provided concrete proof that Girnar – the extinct volcano that Junagadh was built around – was already a major centre of pilgrimage by the 3rd century BC.

In that year, the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka ordered one of his major edicts to be written on a rock below the hill. It is some of the oldest known writing in the subcontinent, inscribed by the Mauryan Emperor soon after he converted to Buddhism.

Did you know that Gujarat had hills like this? And a dormant volcano?

The last Nawab of Junagadh (the guy who tried to join Pakistan) has had a rough reputation:

The life of the last Nawab, Mahabat Khanji III, has been clouded by seventy-five years of mythmaking aimed at ridiculing the ruler and undermining his hugely consequential decision. Today he is remembered in India mostly as ‘a vaguely ridiculous character’, whose eight hundred pedigree dogs each had a private servant.

Sam believes that the Nawab deserves a better reputation:

…the Nawab was a more fascinating figure than he is often given credit for. His dynasty was responsible for saving the Asiatic lion from extinction, and at the time he was regarded as one of the region’s more progressive rulers. He established a multi-faith court, a semi-welfare state and free primary education for all. He banned the slaughter of cows, pioneered animal conservation, and his ancestral hunting grounds are today the only place outside of Africa where lions roam free in the wild.

He then takes up the case of the Partition time shenanigans when Pakistan tried to influence the Junagadh rulers to join their country. Swift and decisive action by India prevented that from happening, and a plebiscite was held in which the state’s residents voted overwhelmingly to be in India.

But many of the Nawab’s relatives stayed back in India. Did you know one of them was the father of a famous Bollywood actress:

Many of the Nawab’s relatives stayed in India, however, including Vali Mohammad Khan Babi, whose daughter Parveen Babi would become a Bollywood sensation.

Look forward to Sam’s book, Shattered Lands.

b. ‘Breaking Baz – India cook up the perfect new-ball formula’ by Sidharth Monga

(Fair warning: This piece is includes some geeky cricket analysis and terms!)

Sid Monga is one of my favourite cricket writers. In this post, he does some smart data storytelling to unearth the key factors that gave India its historic win in the Birmingham test.

He starts by setting the enormity of the achievement – a young team winning without many of its seasoned matchwinners:

India came to Birmingham having lost a Test they had no business losing. It could have been their first win since Durban 2010-11 without any of Virat Kohli, R Ashwin and Rohit Sharma. A landmark win such as this just had to be more dramatic, hadn’t it?

They went on and made it without Jasprit Bumrah, the transcendental leader of their attack.

The following stat is a great example of sharp analysis by the ESPNCricinfo writers:

India won this Test through spectacular results with the new ball. With the first new ball in both innings, India took ten wickets for 243 runs, and 5 for 57 with 9.3 overs of the second new ball. England bowled 93 overs with the two new balls and managed eight wickets. That is where the match was won and lost: 15 for 300 vs 8 for 399.

Monga then looks at the quality of the pace attack and investigates whether Indian bowlers seamed the bowl more (trust the website to measure the average degree of seam for each bowl and analyse that across teams and innings!): the finding was that the Indian bowlers were not having a significantly higher degree of seam, especially with the first new ball.

Monga’s key insight – more than the genius of the Indian bowlers it was the risk-taking attitude of the English batsmen (during the crucial new ball periods) that saw them lose more wickets than India:

Ben Duckett and Zak Crawley were true to their Bazball philosophy, but on this new-ball pitch, it paid to have wickets in hand for when the ball got softer. As much as India’s bowlers stayed on good lengths, it was England’s batting that rewarded them. Test matches are almost always won by the bowlers, but these are not ordinary Test matches. These are pitches and balls that shouldn’t be producing results, but the way England are batting is contriving results. Batting might not be able to win you Tests, but it can lose you on the odd occasion.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘Indian Premier League Cricket’ on the Acquired podcast

This is a fascinating episode about the history of the IPL and features several interesting events and data points that made the league what it is today.

There were parts in this episode where my jaw was dropping… and there were parts where I was totally cringing. Because the two American hosts (Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal) have very little understanding about cricket. The portions where they try to explain cricket to each other are max cringe. Maybe they could have invited an expert (maybe Harsha Bhogle!), to explain the cricketing portions to their American listeners.

That quibble aside, the episode is fascinating.

The duo start with context about why the 4 hour episode is worth a listen:

… this story really isn’t about the game of cricket anyway. It’s about how to create a massively successful sports league from scratch, something that I thought was impossible after doing our NFL and NBA episodes, which each took a hundred years to get to where they are today.

Indian Premier League Cricket started a mere 17 years ago in 2008. Even more than a sports league, the IPL is a case study in how to create the perfect entertainment product

On a per game basis IPL is the second most valuable league (despite being based in a developing country):

Ben: …it is the fastest growing major sports league in the world, growing 20x in value since 2008 to be worth more than $16 billion today. Insanely, the media rights to each match are so valuable that they’re second only to the NFL. The TV broadcast rights, let me just say this again, for each match are worth more than an English Premier League soccer match.

David: Or an NBA game, or a major league baseball game.

Lalit Modi got the idea for a sports league in the 1990s itself:

Lalit as the heir apparent son in this family to this business gets sent to college in the US for his education. First he goes to Pace University and then he transfers to Duke University.

He ends up not finishing and coming back home and rejoining the family business. But when he comes back, inspired by his time at Duke and how basketball crazy Duke is, he’s like, man, the thing that really struck me about America is how sports-crazy everyone is there and how big a business sports is in America, and how big the sports media business is around it. We should get into that.

After initial success with sports channels with Disney, Lalit Modi had a falling out with Rupert Murdoch… and that spices up things a fair bit in this story. As they say “iss kahani mein drama hai, emotion hai, revenge hai”:

David: From Lalit’s perspective, he’s like hey, I started Disney India. I modernized cable in India. I brought sports to India. I did this. And now, all of a sudden I’m out in the cold and I get nothing. In his mind, Rupert Murdoch is the reason that this happened.

Ben: He’s the villain. Rupert stole it away from the Modi family.

David: My sworn enemy from here onwards. And thus begins a 10–15 year journey that is not just the ultimate revenge play by Lalit on Rupert, but accidentally along the way starts the biggest sports entrepreneurial story phenomenon that has ever existed.

India is unique in how much importance we give to just one sport:

David: If you look at American football at the NFL in America, it’s like, I don’t know, 37% or something like that. It is less than 50%. Cricket in India is 93%.

Ben: It’s a one sport country. And it happens to be a one sport country with one of the two largest populations in the world that is growing the fastest in the world.

Lalit made the BCCI realise how it had been underpricing a very valuable asset:

David: Lalit here now in 2005 when he finally gets on the BCCI, the first thing he does is he goes to Sahara and says the price is going up. It is now $1 million, Ben, as you were saying, per day of competition. You are going to go from spending $100,000 a year to spending $105 million per year. Oh, by the way, if you don’t want to do that, that’s fine. I’m happy for you not to do that. I’m then going to go put this out to auction and we’ll see who is willing to pay that.

Ben: Wow.

David: To give you a sense of just how much latent value there is here, I don’t think it goes to auction. I think Sahara just says, okay.

Ben: They’re very aware that this is a very good deal, even at this price.

Some great insights on the smart design of the IPL. One thing they learnt from EPL – no stadium ownership and no debt:

David: The biggest problem in the English Premier League is a lot of teams own their stadiums and then the debt payments that you have to make on these stadiums are just crippling. These are hundreds of millions, if not billion dollar edifices, that you have these teams funding and owning through debt, then the debt payments are just astronomical on top of astronomical player salaries that they’re playing. First thing that Lalit, Andrew Wildblood, and IMG decide is they’re setting up the league, no debt. No team is allowed to have debt, and de facto no team will own their stadiums.

Another key design feature was to ensure that cricket would reach out to an untapped demographic: women. The hosts quote Modi from an old interview:

Lalit Modi: “…all the money that was there in the market that brands had for spending (on cricket) was consumed. There were no more budgets left. We had sucked it all out by taking the price of BCCI in aggregate from a few million dollars to a billion dollars. I had already sucked that money out. When I looked at where are we going to get the money to make IPL work, I needed women and children.”

So international cricket was primarily a male-viewer game. Lalit wanted to change that with the IPL. This is why Bollywood was a crucial part of Modi’s plans (quote from Andrew Wildblood of IMG):

“Apart from Bollywood, Lalit and I agreed that we didn’t want to compete with other cricket. We wanted to compete with the soap operas. We therefore needed to create IPL in the image of a soap opera so that if you didn’t watch last night’s episode, you’re not in the conversation at the water cooler the next morning.

Most households in India were single television homes, and women controlled the remote control watching soap operas at night. The man of the house had little to say in what was seen. So in order to create a successful television product, we had to make something that women would be attracted to, and that’s what caused us to bring in Bollywood.”

The next challenge—Modi had to convince India’s biggest Bollywood superstar, SRK, who… was not a cricket fan:

Lalit knows Shah Rukh Khan, biggest star in India. There’s one problem, though. Shah Rukh is not a cricket fan. He’s into soccer. So Lalit goes to him and is like, I need you to be part of the ownership group.

The story of how Modi got SRK on board is one of the most fascinating hustle-culture stories (apologies, this next one is a long extract!):

David: So Lalit tells the story. Shah Rukh said, Lalit, I don’t know how to do this. My passion is football. I have no idea how to run a team or do anything. Lalit being Lalit, said, Shah Rukh, let me handle it. I’ll put a consortium for you together. You just need to write a check. He (SRK) says, You’re going to take my life savings. It was his life savings in those days. I (Modi) said, just write the check and we’ll talk about it if you end up winning the team at the auction.

This is the most incredible gangster-type stuff. Because Lalit is friends with Shah Rukh, he knows that Nokia, the big handset manufacturer at the time, … is desperate to get Shah Rukh as their celebrity spokesperson in India, and for whatever reason Shah Rukh is not engaging with them on it. Lalit says, Shah Rukh, just trust me. Do I have your word that if I put a consortium together for you, you’re in? He says, sure.

Lalit turns around and he goes to Nokia. He says, I know you want Shah Rukh. He’s not going to do it. But you can become the Jersey sponsor of his new team that he’s about to have in this new cricket league that is going to be the biggest cricket league the world has ever seen.

Ben: Wait, wait. David, I have an alarm bell going off on my head. What do you mean it’s going to be his team. That seems like something you can’t promise when there’s an upcoming auction, and you don’t know how the auction is going to end.

David: Would it be, yeah. Well, if he were to have this new team, he’s going to be in the stands. He’s going to be on the field, he’s going to be wearing it, he’s going to be singing, he’s going to be dancing, he’s going to be doing the music video, introduction to the team in the league. TV cameras are going to be all over him and he is going to be wearing the shirt with Nokia right there in the front on the chest. You can have all of that for the low, low price of $5 million per year in cash upfront.

Ben: Wait, is this to be the Jersey sponsor of one team?

David: Yes. Jersey Sponsor, one team, $5 million in cash. One team that doesn’t exist that theoretically might be won at the auction by Shah Rukh Khan. Theoretically.

Ben: It is crazy the amount of things that need to come together here. This is some major chicken-or-the-egg stuff that does need to come together before a ball is ever bowled. The sponsorships, the media writes, the ownership group, an immense amount of money being promised in contracts, changing hands for a league that has never existed.

David: India, baby.

Ben: And Lalit.

David: And Lalit. He is n incredible entrepreneur. So Lalit goes back to Shah Rukh and he is like, all right. I got you your team. I’m going to set the minimum reserve price in the franchise auction at $50 million, but it’s going to be payable over 10 years. No matter what you bid and what you win, the first year’s payment is going to be $5 million. If you bid $50 million, it’s $5 million a year for 10 years. You bid $100 million, it’s $10 million over 10 years on average, but I’m only going to charge you $5 million in the first. I believe that’s how it was set up.

Listen to the entire episode for some more crazy stories like this (and ignore the cricket explanations!).

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash