The seminal book on the history of innovation

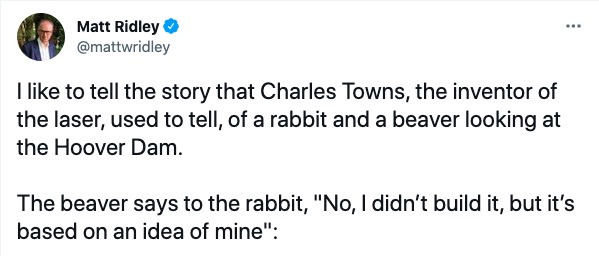

Matt Ridley likes to mention an old joke:

He adds to this:

“All too often discoverers and inventors feel short-changed that they get too little credit or profit from a good idea, perhaps forgetting or overlooking just how much effort had to go into turning that idea or invention into a workable, affordable innovation that actually delivered benefits to people”

This is a quote from a fascinating book that I’m reviewing this week.

Welcome to my content recommendations and reviews for Aug-21: a book, a podcast, articles and a couple of videos.

Let’s get started.

1. Book

a. ‘How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom’ by Matt Ridley

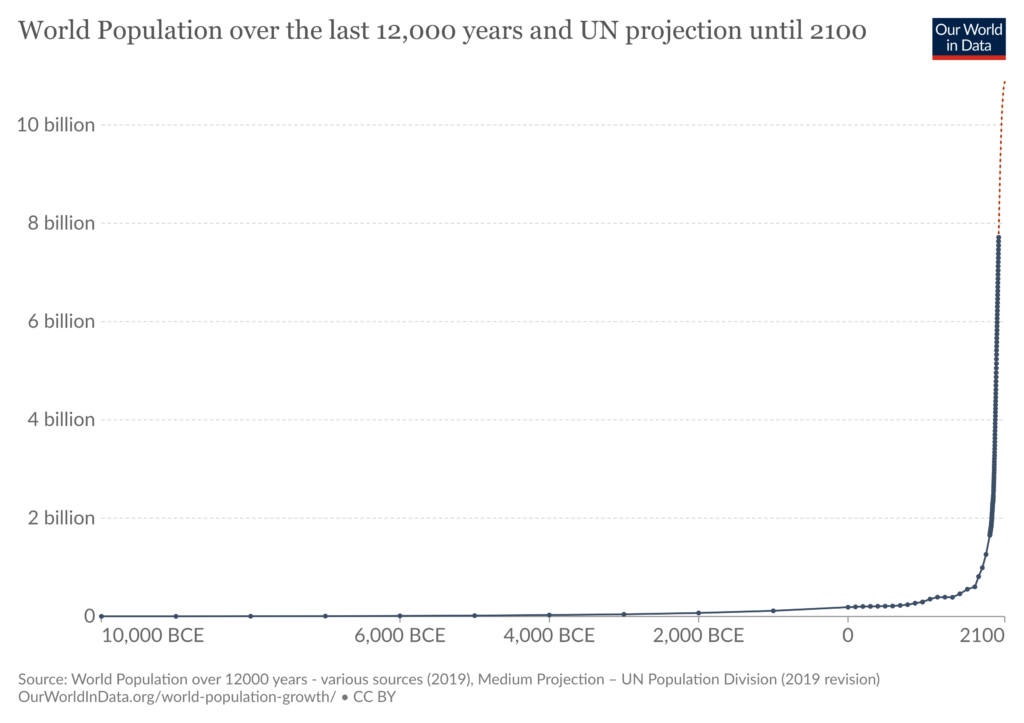

It was while reading another book (The Second Machine Age) that I had come across a staggering chart.

That period – when world population just zooms up – is around 1770, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. A time when it seemed that humankind decided to collectively turn on their innovation switch, leading to the greatest era of prosperity and health we have ever seen on the planet.

Sure, there was innovation before the 18th century. Agriculture, trade, writing… even fire – were all superb ideas that propelled us forward.

What the Industrial Revolution did was to slowly turn up the ‘Innovation dial’ on Earth towards maximum intensity… letting loose an explosion of ever-amazing discoveries and inventions.

Today, of course, that dial is turned up to full-on ‘Beast’ mode.

In this seminal book, Matt Ridley tells this fascinating story of Innovation – through the ages.

It is an astonishing piece of writing, in which, apart from breezing through innovation since the dawn of humankind, he covers areas as diverse as: Energy, Manufacturing, Health, Transport, Food, Communications and Computing.

And he does that by superbly combining two rare skills: the all-encompassing eye of an army commander with the precision of a hand-surgeon. Despite covering so much ground, the book is relatively short at just 400-odd pages.

Ridley has an impressive resume: he’s an accomplished author with several bestselling books (mostly on science, especially genomics), a former science editor at The Economist, a business leader and also a member of the UK House of Lords.

My biggest takeaways from the book were the fascinating patterns that Ridley identifies on innovation.

Here are the five most striking ones (all quotes from the book):

1. The field is more important than the lab:

“For most of the innovations that changed people’s lives, at least at first, owed little to new scientific knowledge and few of the innovators who drove the changes were trained scientists. Indeed many, such as Thomas Newcomen, the inventor of the steam engine, or Richard Arkwright of the textile revolution, or George Stephenson of the railways, were poorly educated men of humble origins. Much innovation preceded the science that underpinned it.”

You don’t need to be a ‘scientist’ or have fancy degrees to be an innovator. All you need is the next ingredient…

2. The importance of tinkering or trial-and-error in invention

Curious, patient and meticulous tinkering is probably the most important feature of innovators.

As a contrast, Ridley offers the cautionary tale of the nuclear energy sector as one impacted by the lack of opportunity to learn using trial-and-error:

“In terms of its energy density, nuclear is without equal: an object the size of a suitcase, suitably plumbed in, can power a town or an aircraft carrier almost indefinitely…

Yet today the picture is of an industry in decline, its electrical output shrinking as old plants close faster than new ones open, and an innovation whose time has passed, or a technology that has stalled. This is not for lack of ideas, but for a very different reason: lack of opportunity to experiment. The story of nuclear power is a cautionary tale of how innovation falters, and even goes backwards, if it cannot evolve. The problem is cost inflation…

The industry remains insulated almost entirely from the one known human process that reliably pulls down costs: trial and error. Because error could be so cataclysmic in the case of nuclear power, and because trials are so gigantically costly, nuclear power cannot get trial and error restarted. So we are stuck with an immature and inefficient version of the technology, the pressurized-water reactor…”

3. You can’t stop an idea whose time has come

“The coincidence of timing is strange, but quite characteristic of inventors. Again and again, simultaneous invention marks the progress of technology as if there is something ripe about the moment.”

Corollary: Sometimes the world may not be ready for a new idea

An idea is not a standalone thing. Like a cog, it needs to fit in the wider ecosystem. That ecosystem needs to be ready.

For instance, Ridley talks about wheeled suitcases:

“Clearly, the problem was not a lack of inspiration. Instead, what seems to have stopped wheeled suitcases from catching on was mainly the architecture of stations and airports. Porters were numerous and willing, especially for executives. Platforms and concourses were short and close to drop-off points where cars could drive right up. Staircases abounded. Airports were small.

The rapid expansion of air travel in the 1970s and the increasing distance that passengers had to walk created a tipping point when wheeled suitcases came into their own.

The lesson of wheeled baggage is that you often cannot innovate before the world is ready. And that when the world is ready, the idea will be already out there, waiting to be employed…”

I loved that last line – as an entrepreneur, you need not even ask: What can I invent? You can just explore – what idea is already out there, but was perhaps too early for its time?

4. Not all inventors end up wealthy

“I have chosen to tell the stories of Newcomen, Watt, Edison, Swan, Parsons and Steinsberger, but they were all stones in an arch or links in a chain. And not all of them ended up wealthy, let alone their descendants. There is no foundation named after any of them today and funded by their wealth.”

They may not have ended up wealthy, but probably many of them were doing it for the thrill of innovating itself. Having said that, there is a tenuous link between creating something new and useful… and being able to profit from it.

5. There’s a long and hard road to turn a discovery/invention into an innovation

Paraphrasing Peter Thiel, you may have the product, but do you have the distribution?

Ridley mentions the case of penicillin, and how it took a lot of work after its (lucky) discovery to make it a global success:

“(The results of trying) penicillin as a topical antiseptic applied to infected wounds were disappointing. Nobody yet realized that it worked best if injected into the body. Also, it was hard to produce in quantities or to store. Notoriously, in 1936, the pharmaceutical company Squibb concluded that ‘in view of the slow development, lack of stability and slowness of bacterial action shown by penicillin, its production and marketing as a bactericide does not appear practicable.’ So penicillin languished as a curiosity…

The story of penicillin reinforces the lesson that even when a scientific discovery is made, by serendipitous good fortune, it takes a lot of practical work to turn it into a useful innovation.”

Incidentally, startups are often told – create painkillers, not vitamins. Well, penicillin (an antibiotic) is as close as it gets to being a painkiller. And yet it struggled to get acceptance…

The book has several such high value lessons on how innovation actually happens. In addition to these lessons, it’s also got a great set of storytelling techniques to learn from.

Several Storytelling lessons

Here are four techniques that stood out for me: .

1. Mystery/buildup

A good storyteller never lets a surprising fact go without a drumroll-type announcement.

For instance, instead of simply saying:

“The first controlled conversion of heat to work was the most important event in the history of humankind”

…here’s what Ridley says:

“Possibly the most important event in the history of humankind, I would argue, happened somewhere in north-west Europe, some time around 1700, and was achieved by somebody or somebodies (probably French or English) – but we may never know who. Why so vague? The event I am talking about is the first controlled conversion of heat to work, the key breakthrough that made the Industrial Revolution possible if not inevitable and hence led to the prosperity of the modern world and the stupendous flowering of technology today.”

The buildup he uses creates immense curiosity around the concept… and also makes you appreciate it more.

2. Clutter breaking insights

When you research such a wide array of material, you would naturally be pondering about them all the time. During such periods of reflection, you might come across a gobsmacking insight that suddenly explains a lot in a surprising yet simple way.

This is one such insight from the book:

“The main theme of human history is that we become steadily more specialized in what we produce, and steadily more diversified in what we consume: we move away from precarious self-sufficiency to safer mutual interdependence.”

Ponder on that a bit!

3. Surprise – using norm and variance

Which form of energy is the most dangerous? Is it:

Coal

Biofuels

Gas

Hydro

Solar

Wind

Nuclear

Surely, your answer would be ‘Nuclear’?

Surprise! It is the lowest, according to one study cited by Ridley:

“According to one estimate, per unit of power, coal kills nearly 2,000 times as many people as nuclear; bioenergy fifty times; gas forty times; hydro fifteen times; solar five times (people fall off roofs installing panels) and even wind power kills nearly twice as many as nuclear. These numbers include the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima.”

Wow.

4. Fascinating incidents

The chapter on food is incredibly deeply researched. Ridley dives into the history of what drove the ‘Green Revolution’ which ensured that India (and other populous, poor countries) did not see mass starvation (something which was predicted by many leading scientists of that time).

Here’s Ridley sharing the story of an incident between the food scientist, Normal Borlaug and Ashok Mehta, a senior Indian government official:

“Borlaug’s long campaign culminated in a stormy meeting on 31 March 1967 with the deputy prime minister and head of planning, Ashok Mehta. Borlaug decided to throw caution to the winds. In the midst of an argument, he yelled: ‘Tear up those five-year plans. Start again and multiply everything for farm support three or four times. Increase your fertilizer, increase your support prices, increase your loan funds. Then you will be closer to what is needed to keep India from starving. Imagine your country free of famine . . . it is within your grasp!’

Mehta listened. India doubled its wheat harvest in just six years.”

A minor quibble

One minor quibble about the book: In some parts Ridley’s writing assumes that the audience ‘gets’ science terms. For instance he says:

“He redesigned dynamos to generate electricity from turbines and within a few years the first electric grids were being built with larger and larger Parsons turbines.”

Reading this, I was like: “What’s a dynamo?” Surely a writer cannot assume that all readers would know that.

Overall though, ‘How Innovation Works’ is a must-read for anyone interested in knowing about this fascinating topic.

2. Podcast

Naval Ravikant Podcast: Interview with Matt Ridley

Naval Ravikant (just known as Naval to his legions of adoring fans) is a Silicon Valley institution. There are Twitter accounts called @NavalBot, @QuoteNaval, @NavalismHQ, all of which are dedicated to sharing extracts/quotes from Naval’s work!

(There’s a book called “The Almanack of Naval Ravikant” written by someone, who’s presumably a fan)

Anyway, here’s what Naval says about Matt Ridley in the podcast intro:

“I don’t have heroes, but there are people who I look up to and have learned a lot from, and Matt Ridley… has got to be near the top of that list. Growing up, I was a voracious reader, especially of science. Matt had a bigger influence on pulling me into science, and a love of science, than almost any other author. His first book that I read was called Genome. I must have six or seven dog-eared copies of it lying around in various boxes. It helped me define what life is, how it works, why it’s important, and placed evolution as a binding principle in the center of my worldview.”

And here’s what he says about who this book is for:

“So I recommend this book for two classes of people. One is innovators and would-be innovators themselves. If you’re an entrepreneur in Silicon Valley, Shanghai or Bangalore and you’re thinking about creating products—whether it’s social media, launching rockets, building airplanes or genetic engineering—you need to read this book because it will give you a better view of the history of innovation as well as the future of innovation than any other book that I know of.”

I think the podcast episode (which is in 2 parts) is great listening for those who wouldn’t have time to read the book… or (like me), would like to get introduced to the ideas in the book before picking it up.

3. Articles

a. ‘Geography is the chessboard of history’: by Tomas Pueyo

Tomas Pueyo is an unlikely storyteller, but one who became a viral sensation after his article on Covid-19 in March 2020 was read by millions.

In this article, he tackles a different subject: geography.

Tomas discusses the importance of geography in the development of Europe. It’s a theme that has fascinated me ever since I read “Guns Germs and Steel” several years ago. Tomas does a great visual job of telling the story of why Northern Europe was geographically better endowed to do well or why the Greek empire was destined to be overtaken by another power.

b. Betting on things that never change by Morgan Housel

Few writers pack in so much wisdom in such less space, as Mr. Housel.

In this write up he lays out the two fundamental opposing forces that work in investing: Betting on Change vs Betting on Compounding benefits of things remaining the same.

Here’s a brilliant line from the piece:

“Every successful investment is some combination of change that drives competition and things staying the same that drives compounding. There are so few exceptions to this, regardless of size or industry”

I also loved this line by VC leader Marc Andreesen, where he’s comparing the difference between his own investment approaches and that of Warren Buffett:

“[Warren is] betting against change. We’re betting for change. When he makes a mistake, it’s because something changes that he didn’t expect. When we make a mistake, it’s because something doesn’t change that we thought would. We could not be more different in that way.”

c. Money Stuff (email newsletter) by Matt Levine

I think Matthew Levine is either:

a. An alien from another planet

b. The generic name for 5 clones who all look, speak and write the same

c. An AI program that is from the future.

I refuse to believe that one individual could be so productive and so good.

His daily newsletter, ‘Money Stuff’, on the world of finance and business, is super-popular, reaching 150K+ readers. More importantly, the emails are incredibly insightful, insanely witty (I mean, I’ve laughed out loud several times) and if that weren’t enough, intensely long!

Also did I mention it’s a daily newsletter? As in it comes every day of the week. Every. Single. Day… Matt writes 4,000+ words of funny, high-quality analysis of Wall-Street happenings, without fail.

As I said, we’re dealing with an alien, clones or an AI program. Take your pick.

Meanwhile, here is a (relatively) small sample from one of his recent emails – on the story of the employees of Archegos Capital who lost their bonuses worth $500M:

“If you worked for Bill Hwang’s family office Archegos Capital Management and you got a bonus, part of your bonus was automatically invested in Archegos’s fund and stayed there until you left the firm. This is standard stuff: If a lot of your money is tied up in the fund, then you will have incentives to work hard to make the fund go up, and not to mess up and make the fund go down. The first set of incentives worked: Employees put “under $50m” of deferred compensation into the fund, and they “saw the value of their deferred bonuses soar to about $500m” by earlier this year, because Archegos was, for a while, really good at making money.

The second set did not, because Archegos was also really good at losing money. It blew up in March, and the employees’ money appears to be gone:

‘Yet some former employees have not received any of their deferred pay, including the original sums. One person close to the firm told the FT that “the money is gone” with “no pot of gold to pay them from”. Another said Archegos employees “are in a difficult position” and “warrant sympathy”’.

Yes look, I do kind of think that if you work at an investment firm and a portion of your bonus has to be invested in the firm’s fund, that really is because part of your job is to try to keep the fund from going to zero? Kind of a big part of your job, really? And when the fund then does go to zero you have to be like “well I guess my bonus is gone”? I do not want to be too unsympathetic here, I realize that Hwang seems to have been the decision-maker and the employees could not necessarily have gotten a better outcome, but still. They ran an investment fund that lost all of its money and also inflicted multibillion-dollar losses on its banks. It does seem sort of strange to expect a bonus.”

Oh, by the way, you can sign up for the newsletter here.

4. Videos

a. ‘My English is not good enough’ – Roger Federer (1:50)

You are a genuine legend. You’ve won 20 Grand Slam titles and been world no. 1 for years on end.

And you have just won a gruelling match in the most prestigious tournament of your sport.

And, when an interviewer asks you a simple question, one that includes a phrase (a simple phrase “absence makes the heart grow fonder”) that is not native to your mother tongue… you

– Eschew the temptation to faff

– Avoid the route of just smiling and mumbling some vague response and

– Refrain from trying to infer some meaning for those words…

Instead you own up to your ignorance and state clearly: “Sorry, I don’t understand that saying. My English is not good enough”.

That takes courage and vulnerability. True legend.

b. How to Play the Perfect Villain by Foil Arms and Hog (3:53)

This video by the Irish comedy trio (one of my favourites) is really different. I loved how they broke down the process of making something or someone appear evil!

It starts off all goofy. Then, in the middle, things gets goosebumpy… and then ends with mirth again.

Brilliant breakdown of how to emote evil.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the month.

Photo by Jocelyn Morales on Unsplash