The most consequential napkin art of all time (or was it?)

Today being the first Saturday of the month, it is time for my content recommendations – books, a podcast, articles and videos.

Let’s get started

1. Books

a. ‘Narrative Economics’ by Robert Shiller

On the 13th of September 1974, probably the most famous curve of all time was drawn on a table napkin in a restaurant in Washington DC.

Here’s the scene. Four men at the table. A journalist (Jude Wanniski, who was the one who later wrote about it), two top White House officials (future VP Dick Cheney and future Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld) and the our main guy – an economist named Arthur Laffer.

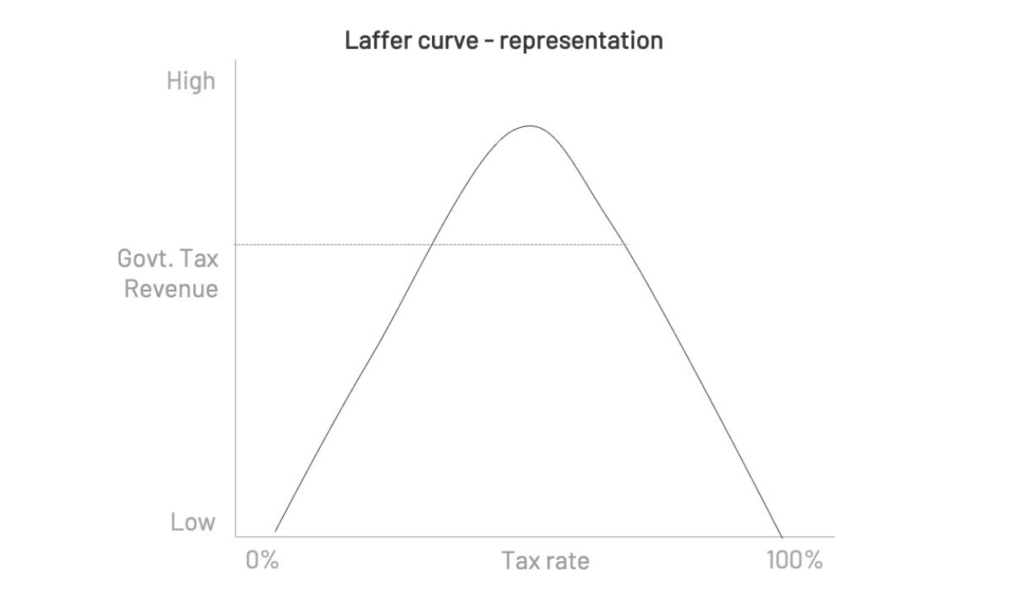

During that lunch meeting, Laffer takes a table napkin and hand-draws a graph to indicate that tax rates can be reduced without any impact on government tax collections. How is that possible, you ask? So imagine a graph with tax rate on the X-axis and collections in the Y axis. At 0% tax, the government’s revenue would be zero. At 100% tax, the government’s revenue would still be zero – since no one would have incentive to earn income.

The magic happens in the middle. Assume an inverted-U shaped curve stretching from 0 to 100%. Moving down from 100%, you will find that at any of the high tax rates, the government could earn a similar tax revenue at a lower tax rate – as shown in the image below:

That famous napkin is now a treasured artifact at The National Museum of American History.This might have been an obscure incident in a random DC restaurant forgotten by all involved. Except the ‘Laffer Curve’ later became the inspiration for a major tax cut by a future President Ronald Reagan – and a whole new economic and tax policy christened as Reaganomics.

But here’s the tricky question: Did this napkin-drawing incident really happen?

Probably, no.

Here’s the economist Art Laffer himself:

“I personally do not remember the details of that evening, but Wanniski’s version could well be true. I used the so-called Laffer Curve all the time in my classes and with anyone else who would listen to me to illustrate the trade-off between tax rates and tax revenues. My only question about Wanniski’s version of the story is that the restaurant used cloth napkins and my mother had raised me not to desecrate nice things.”

A story of a famous drawing on a napkin – one that inspired a major economic policy shift – is being disputed by the main actor himself!

I found that fascinating… More interesting is Prof. Robert Shiller’s (the book’s author) take on why the story became viral:

“The story’s rich visual imagery helped it evolve from an economic anecdote into a long-term memory… There is a lesson to be learned here for those who want their stories to go viral: when authors want their audience to remember a story, they should suggest striking visual images.”

That’s some good advice – and it is from the book, ‘Narrative Economics’ – written by Prof. Robert Shiller (an Economics Nobel laureate who teaches at Yale). It argues that beyond numbers and data, narratives have immense power – power to move entire countries and economies.

What a riveting premise for a book, I thought. It should make for arresting read… right? Um, yes and no.

So here’s the deal – the book is fascinating (in parts). And as you would expect, it is based on meticulous research. But, as you might also expect, Prof. Shiller is no storyteller. So the book is also a drag (in parts) – and I found it challenging to complete it.

Having said that, these are some of the fascinating highlights that stood for me:

– The Prof (very seriously) compares the spread of narratives to the spread of viral diseases and uses concepts from epidemiology to study the same (what a coincidence that his book releases in the midst of a once-in-a-generation pandemic).

– Often it’s not an individual story, but a ‘constellation of narratives’ that aid in changing society’s views on a particular topic. Movies and popular books have a significant role to play here. For instance, a movie like 3 Idiots is still remembered for its message of not getting caught in the academic rat race. Charlie Chaplin’s classic ‘Modern Times’ was a biting satire on the over-dependence on machines and the loss of the human touch.

– Narratives recur. For instance, take this paragraph:

“Whenever a man is replaced by a machine a consumer is lost; for the man is deprived of the means of paying for what he consumes. The greater the number of Robots employed, the less is the demand for what they produce for men cannot consume what they cannot pay for.“

Can you guess when this was written?

It is from an article in the Los Angeles Times.

From 1931.

As part of the book, Prof Shiller documents 10 recurring narratives (for instance ‘labour-saving machines will replace all jobs’) that will continue to make headlines.

For instance, there was a massive resistance to move to self-dial telephones in the early-20th century (earlier, you had to first talk to an ‘operator’ who would connect you to the person you wanted to talk to). Here’s Prof. Shiller:

“The transition from the non-dial telephone to the dial telephone took many decades. However, during the Great Depression, there rose a narrative focus on the loss of telephone operators’ jobs, and the transition to dial telephones was troubled by moral qualms that by adopting the dial phone one was complicit in destroying a job.”

This story got me thinking. If they were SO wrong about something then … what are we wrong about today?

More such thought-provoking questions are sure to be raised when you read this book.

In sum, would I recommend this book for everyone? No, it’s not an easy read.

But I would highly recommend it for serious students of both – economics and storytelling.

b. ‘Tyranny of Metrics’ by Jerry Muller

‘Data is the new oil, Storytelling is the new refinery’ is a line that I like to say.

It assumes that more data = better.

No, says Jerry Muller.

In a compellingly argued book, Prof. Muller uses a diverse set of examples to give a dire warning – Do. Not. Over. Rely. On. Metrics.

While management theory might tell you “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it”, Prof. Muller’s point counters that with, broadly, this line of argument:

– What you are seeking to measure may not be the right metric

– Even if right, It may not be measurable

– Even if measurable, it may not be worth rewarding for

– Even if worth rewarding for, it might be gamed resulting in an overall skewed result

In separate chapters, he argues about the ills of over-reliance on metrics across diverse sectors: Education, Health, the Military, Police, Business and Philanthropy.

Here are some of the more egregious examples

– Health: In the UK, an NHS policy to penalise longer Emergency waiting times went awry. Here’s the author:

“In England, in an attempt to reduce wait times in emergency wards, the Department of Health adopted a policy that penalized hospitals with wait times longer than four hours. The program succeeded—at least on the surface. In fact, some hospitals responded by keeping incoming patients in queues of ambulances, beyond the doors of the hospital, until the staff was confident that the patient could be seen within the allotted four hours of being admitted.“

Ok so that was predictable…(in hindsight)!

- Higher Education: US Universities have a ranking system, which leads to some, well, interesting implications. Here’s an observation:

“Recently I was puzzled to find that a mid-ranked American university was taking out full-page advertisements in every issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education, touting the important issues on which its faculty members were working. Since the Chronicle is read mostly by academics—and especially academic administrators—I scratched my head at the tremendous expenditures of this not particularly rich university on a seemingly superfluous ad campaign. Then it struck me: the USNWR ratings are based in good part on surveys of college presidents, asking them to rank the prestige of other universities. The criterion is of dubious validity, since most presidents are simply unaware of developments at most other institutions. The ad campaign was aimed at raising awareness of the university, in an attempt to boost the reputational factor of the USNWR rankings.”

- Business: An example he (surprisingly) doesn’t mention is that of the late Jack Welch, the celebrated ex-CEO of General Electric. Lionised by the media during his tenure, Welch’s obsession with ‘shareholder-value-above-all’ as a metric, led to a lot of decisions that proved to be harmful in the long-term for the company. This Bloomberg article minces no words in lacerating his legacy. Here’s an extract:

“Because Welch was so idolized, the path he trod became the path every other CEO trod as well. They all began focusing on shareholder value. That became the basis on which they were judged and paid. And it warped the business culture, causing companies to put employees, vendors and even customers behind the primacy of shareholders. If you want to see what happens when you take maximizing shareholder value to its logical extreme, I give you Facebook. Or, for that matter, Enron…. When you see pharmaceutical companies raising the price of drugs to unconscionable levels; when companies cut back on research and development to satisfy Wall Street; when CEOs routinely make $40 million to $50 million a year, you now know whom to blame. Jack Welch.“

Apart from the use of diverse examples, Prof. Muller is also good with words. For instance, I loved this line:

“The more that work becomes a matter of filling in the boxes by which performance is to be measured and rewarded, the more it will repel those who think outside the box”.

You might read all this with growing concern about the downsides of metrics (like I did) and wonder: What is the solution?

Now that’s where the issue lies. While Prof. Muller’s book makes for a compellingly savage anti-metrics rant, there’s hardly any mention of the solution… The only point the Professor makes is: Use your own judgement.

Um, ok. That helps, I guess…

This line, however, summarises the book’s idea well:

“Ultimately, the issue is not one of metrics versus judgment, but metrics as informing judgment, which includes knowing how much weight to give to metrics, recognizing their characteristic distortions, and appreciating what can’t be measured.“

I think the book is essential reading, and a timely warning, for those of us who have become too reliant on metrics… and while it doesn’t provide much of a solution, it might be the correcting influence we desperately need.

2. Podcast

a. ‘North Star’ by David Perell – Interview with Balaji Srinivasan

David Perell is a young internet whizkid who’s built a super-popular online writing course called Write of Passage. He built his popularity by creating superior content – long-form blog posts, newsletters, tweetstorms (yes!) and a podcast.

In the podcast, he interviews successful people from across fields and gleans their secrets. This one is with Balaji Srinivasan, a Silicon Valley star and General Partner at leading VC firm, Andreesen Horowitz.

Srinivasan’s thought clarity and vision is staggering. One concept that I found fascinating was ‘on-chain’. Here’s an extract:

Srinivasan: “So, on-chain is the next step after online. And what that means is it’s not just accessible on a server that might go down at some point, it is posted on a blockchain, which will never go down…

… So what you can get is, especially with post-it on-chain, you’ll get timestamps, you’ll get a digital signature as to who posted it. You get a hash of what was posted. And so you can prove mathematically who posted what, when. Right. Or at least what entity would this digital signature, what data at what time, and why is this important? Because it’s digital history. It’s unfalsifiable history. So to give you three examples of how this record of all of these facts could resolve things.

Six years ago, Tesla had a issue where NYT wrote an article saying that their car had stalled out on the side of the highway. And they pull the instrumental record, and they showed that that article was not true, that it had not actually stalled out in that way. Right? And so that was something where the instrumental record, the ledger of record was able to falsify the words on top. The numbers took precedence over the letters. Second example, last year, the Brazilian fires, Emmanuel Macron retweeted a photo of supposedly of the Brazilian fires, and the New York Times printed this tweet, put it in an article. And it turns out that photo was taken by a photographer who died in 2003. So the photo was at least 15 years old. And so again, a timestamp basically show that the story about the Brazilian fires was false…

Third example in China recently, two years ago, a court in Hong Sao went and proved that a patent dispute, the litigant was incorrect because the defendant had actually put their patent or the contents of patent on-chain before that infringement had actually occurred. So a third example of where a timestamp resolve the dispute.“

3. Articles

a. 20 questions for clarity in writing by Roy Peter Clark

Roy Peter Clark is a revered writing teacher based in the US. In this thought-provoking post, he says that good writing should aim for three goals: It must be Accurate, Clear and Interesting. He then focuses on the second goal and puts down 20 questions (that are great direction-pointers) that would help you to sharpen your writing from a clarity point of view.

For instance, I loved the way this question was worded:

“Can I find a “mentor example,” a microcosm or small world that represents a larger reality, an intensive care unit rather than a whole hospital complex.“

The ‘mentor example’ – is kind of the approach I take when I do the book reviews!

b. Narrative Mirages and Narrative Violations by Bedrock Capital

When investors can write well, it’s a boon. You get a highly informed birds-eye view … in simple-to-understand language.

In this letter, Geoff Lewis and Eric Stromberg of Bedrock Capital (which manages US$500M across 2 funds) lay out their investment philosophy.

They make three points

– Narrative matters in investing (especially in the internet age)

An extract: “Just as capital powerfully influences our behavior, so too does narrative. Narrative is an extraordinary force that helps us make sense of the world. The most popular narratives are often accepted as truths. Yet we forget that narratives are not synonymous with truth. They can reflect what people wish were true, what would make people rich if they were true, or simply what an algorithm spits out as truly profitable. The internet fundamentally disrupted the process of narrative formation and dissemination. It enabled popular narratives to form and spread at hyperspeed; algorithmically optimized to draw us in without question.”

(Prof. Shiller would agree)!

– Investors often fall prey to ‘Narrative Mirages’

“Popular narratives at the category layer tend to be the most troublesome. Surging capital and spiraling narratives about the next huge market catalyze to form a perfect storm. Whenever an easily understood and easy to replicate new startup shows even a glimmer of promise, the hallucinations kick in. New global categories are conjured up in mere days based on a nascent startup’s early success. If it can be cloned, it will be cloned. Remixed, reused and repackaged with a superficially different veneer by dozens of teams. Each funded by dozens more investors. Location-based marketing. Daily deals. Wearables. Chatbots. In the end, each category proved nothing more than a narrative mirage.”

(Emphasis mine)

– Investors should instead look for ‘Narrative Violations’

“Rather than chase popular narratives, Bedrock’s approach is to invest when companies are incongruent with the narrative. Simply put, we search for narrative violations… Founders Fund invested in SpaceX shortly after their second rocket blew up; the popular narrative was that the company was about to blow up as well. Andreessen Horowitz’s second investment was in Skype, at a time when the popular narrative was that Skype was in a death spiral.“

The authors share examples for each category.

Of course, from a critical point of view, you could say that the examples have been cherry-picked… Also, how does one differentiate from a ‘Narrative violation’ and just plain ‘being wrong’?!

Still, it makes for fascinating reading.

(Hat tip – Guru Sundaram).

4. Videos

a. Ryan Reynolds – New ManageMint

Probably my favourite superhero movie is Deadpool, with the irrepressible Ryan Reynolds playing the sassy, motormouth ‘superhero’. Over the years, I’ve gotten more in awe of this genuinely funny actor – especially seeing the series of his quirky, irreverent “ads” for various products that he owns/endorses.

This super-funny ad starts off with the standard visually arresting video… and then quickly stoops to a regular PowerPoint Presentation. He ends with “Every presentation needs Next Steps”. Hilarious.

You can binge on more RR here. Warning – not kid-friendly!

b. Economics Rap battle

I heard about this unusual video on a podcast called EconTalk. It creates a fictional ‘rap-battle’ between two 20th century intellectual giants of the economics profession – John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. Both had very differing views to tackling recessionary conditions, and the rap battle presents a fun, quirky take on what the two approaches mean.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the month.

Stay safe and healthy!

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash