A relatable introduction to Philosophy

This week I’m reviewing a book after a long time – but one worth the wait. It’s an introduction to philosophy written, appropriately, by a comedy writer.

📘 Book of the week

a. ‘How to be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question’ by Michael Schur with Todd May

Michael Schur is a highly successful, Emmy-award winning writer/co-creator of several US sitcoms including: The Office, Parks and Recreation, A Good Place, and perhaps my favourite, Brooklyn Nine-Nine.

A sitcom writer authoring a book on philosophy? How does that work, you may wonder?

Well sometimes, to write about a complicated subject, all you need are three things: basic intelligence, great writing skills and a ton of curiosity. And Michael has all three, in spades.

Mike graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard University in 1997, with a B.A. major in English. So he’s got the smarts. He’s written a mountain of stuff for demanding TV shows, so he’s got that writing experience under the belt. And his relentless curiosity and admirable moral compass, which shine through on every page, make him eminently suited for this endeavour.

So I’d been waiting for a book like this for a long time. I’m interested in philosophy, but did not have the patience to dig through dense, difficult documents that are a chore to understand. I did try some books which were supposed to be introductory texts, but didn’t get anywhere.

Thankfully, Mike has done the incredibly hard work of reading the source texts of several philosophical tomes for us – and then distilled the essence of the different approaches into one readable book.

He first shares why we should read philosophy – to make better, more deliberate decisions that come from a place of awareness.

Most people think of themselves as “good,” and would like to be thought of as “good.” Consequently, many (given the choice) would prefer to do a “good” thing instead of a “bad” thing. But it’s not always easy to determine what is good or bad in this confusing, pretzel-twisty world, full of complicated choices and pitfalls and booby traps…

…this book hopes to boil down the whole confusing morass into four simple questions that we can ask ourselves whenever we encounter any ethical dilemma, great or small: What are we doing? Why are we doing it? Is there something we could do that’s better? Why is it better?

Once he establishes the need for learning philosophy, the rest of the book dives into different philosophical approaches (mostly by taking a historical approach to the subject) along with colourful descriptions of the people who came up with them.

There are several reasons why Mike’s book is a great read. Apart from the subject matter itself, what I enjoyed is the funny, relatable and concrete approach he takes to the subject. Here are some specific elements I loved about the book.

1. Relatable examples throughout

Mike introduces some of the most esoteric philosophical approaches and then applies them, not to solve major existential questions such as religion or democracy or capitalism…, but instead to answer simple (almost trivial) questions, such as:

- After a visit to a shopping mall, should I return the shopping cart back to where they are stored, or leave it near my car?

- Should I buy a new phone, when there’s so much poverty around me?

- Should I lie to my friend that I like her ugly dress?

- We’ve Done Some Good Deeds, and Given a Bunch of Money to Charity, and We’re Generally Really Nice and Morally Upstanding People, So Can We Take Three of These Free Cheese Samples from the Free Cheese Sample Plate at the Supermarket Even Though It Clearly Says “One Per Customer”

The idea is that philosophy can be used on simple everyday issues too.

(Incidentally many of these questions figure as Chapter names! Essentially Mike is clear that his focus is on application not theory for theory’s sake)

2. Everyday language

I loved this instance of how Mike transitions from utilitarianism/consequentialism to the means-focused ideas of Immanuel Kant. (Utilitarianism? Kant? I know, I know. I’m name-dropping here. But that’s how “smart” I feel after reading the book).

what if we could go back to that Universe Goodness Accountant from the introduction, who tsk-tsked us for all the bad results we got, and say, “Hey, lady—we don’t care if our day of good deeds got all screwed up, because we meant to do good things and only our intentions determine our moral worth”? Wouldn’t that feel good, to rub it in her face a little? Buckle up, people. It’s (Immanuel) Kant time.

3. Humour that shines through!

I was chuckling reading this:

It’s estimated that less than a third of what he (Aristotle) actually wrote has survived, but it covers the following subjects: ethics, politics, biology, physics, math, zoology, meteorology, the soul, memory, sleep and dreams, oratory, logic, metaphysics, politics, music, theater, psychology, cooking, economics, badminton, linguistics, politics, and aesthetics. That list is so long I snuck “politics” in there three times without you even noticing, and you didn’t so much as blink when I claimed he wrote about “badminton,” which definitely didn’t exist in the fourth century BCE.

4. Insightful lines that make you think and ponder the implications

“Should I tell the truth?” is one of the most common ethical dilemmas we face. Most of us don’t enjoy misleading people, but the gears of society do mesh more smoothly if we grease them with white lies.

The tussle between individualistic and collective societies:

consider for a second his (Rene Descartes) famous Enlightenment formulation Cogito, ergo sum—the aforementioned “I think, therefore I am”—which, again, is one of the very foundations of Western thought. When we place it next to this ubuntu formulation—“I am, because we are”—well, man oh man, that’s a pretty big difference.

5. Humanising lofty philosophers, poking fun at their eccentricities and making them relatable in present-day terms with analogies

We have now arrived at the second of our three main Western philosophical schools: utilitarianism, most famously developed by British philosophers Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806– 1873), two deeply weird dudes.

Interestingly, utilitarianism is popular currently, given that Sam-Bankman Fried or SBF (the crypto billionaire who had a very public fall from grace) was touted to be a star adherent of this philosophy.

Moving on, here’s Mike describing the dour philosopher, Immanuel Kant:

Perhaps what we need is a real stickler. A stern hardass who crosses his arms disapprovingly when we equivocate. A no-nonsense Germanic dad who will look at our moral report card, see five A’s and one A-minus, and ask: “What happened with the A-minus?” We need Immanuel Kant, and the philosophical theory known as deontology.

Here’s a couple of analogies Mike uses to describe why Kant was such a big deal:

Whether you agree or not, Kant’s hard-core brain-based theory was a seismic event in Western philosophy; his monumental influence can be understood only when you see how many contemporary philosophers worked from his source material. He’s sort of like Hitchcock in film, or maybe Run-DMC in hip-hop: he had a massive influence on those who came after him.

‘How to be Perfect‘ is a highly recommended and essential ‘quick start guide’ to the fascinating world of philosophy.

📄 Article/s of the week

a. What Moneyball-for-Everything Has Done to American Culture by Derek Thompson

In this article, Derek provides a counterpoint to the dominance of data-driven decision making approaches to sports, movies and music. His point: while too much reliance on this tool might have optimised team composition and on-field tactical decisions… this optimisation has come at the cost of the game’s beauty itself.

Essentially it’s a case of optimising for the wrong objective. Derek puts it in the frame of finite vs. infinite games:

The religion scholar James P. Carse wrote that there are two kinds of games in life: finite and infinite. A finite game is played to win; there are clear victors and losers. An infinite game is played to keep playing; the goal is to maximize winning across all participants. Debate is a finite game. Marriage is an infinite game. The midterm elections are finite games. American democracy is an infinite game. A great deal of unnecessary suffering in the world comes from not knowing the difference. A bad fight can destroy a marriage. A challenged election can destabilize a democracy. In baseball, winning the World Series is a finite game, while growing the popularity of Major League Baseball is an infinite game. What happened, I think, is that baseball’s finite game was solved so completely in such a way that the infinite game was lost.

I really loved that frame applied to this phenomenon. So before we go ahead and apply massive computational resources to solve a problem, we should always step back and ask ourselves – are we optimising for the right objective?

Also, I worry – will cricket follow a similar trajectory?

b. FTX’s Balance Sheet Was Bad

The peerless, hilarious Matt Levine is hitting everything out of the park this week. With the FTX saga ruling airwaves in the world of finance, we are lucky to be having a chronicler like him.

Take this section (emphasis mine):

If a troubled company has a few days to beg potential investors for a bailout before it files for bankruptcy, and it sends those investors its balance sheet so they can consider investing, and they all pass, and then the company files for bankruptcy, of course the balance sheet was bad. That is not a state of affairs that is consistent with a pristine fortress balance sheet.

But there is a range of possible badness, even in bankruptcy, and the balance sheet that Sam Bankman-Fried’s failed crypto exchange FTX.com sent to potential investors last week before filing for bankruptcy on Friday is very bad. It’s an Excel file full of the howling of ghosts and the shrieking of tortured souls.

🤣🤣

Or this one:

But then there is the “Hidden, poorly internally labeled ‘fiat@’ account,” with a balance of negative $8 billion. 1 I don’t actually think that you’re supposed to subtract that number from net equity — though I do not know how this balance sheet is supposed to work! — but it doesn’t matter. If you try to calculate the equity of a balance sheet with an entry for HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT, Microsoft Clippy will appear before you in the flesh, bloodshot and staggering, with a knife in his little paper-clip hand, saying “just what do you think you’re doing Dave?” You cannot apply ordinary arithmetic to numbers in a cell labeled “HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT.” The result of adding or subtracting those numbers with ordinary numbers is not a number; it is prison

Genius.

🎧 Podcast episode/s of the week

a. Tim Ferriss interview with Michael Schur

If you don’t get the time to read Mike’s book (reviewed above), then this podcast episode is a great alternative. Tim Ferriss asks probing questions, and Mike is a delightful raconteur.

If there is one section that I absolutely loved – and I highly recommend that everyone read – it is a story that Mike shares about his ‘failure” experience from having worked at Saturday Nite Live (SNL). It’s a long extract, but features superb storytelling and holds a powerful life lesson:

Mike: …so here’s how SNL works. On the Monday and Tuesday of every week, you sit around your office and you goof around and you write sketches. And usually, the way it usually goes, is you stay up Tuesday night until like nine in the morning, you stay up all night and you write all night. And then on Wednesday there’s a read through. The host comes in, and Lauren comes in, and the cast sits around a giant table. And the crew piles into this room, and they read through 45 or 50 sketches over four hours, and just one after another, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. And then there’s a meeting afterwards, and Lauren and the head writers, and producers, and the host, all kind of pick, here are the dozen sketches we’re going to do this week.

So there’s a specific kind of failure at SNL that is so painful and visceral, that I still, and this is not an exaggeration, it’s not, I’m not saying this for effect. I still have occasional nightmares about this particular failure, okay? The particular failure is, it’s the third hour of the read through, your sketch is number 28 in the rundown. Lauren reads the title of the sketch here, this title, okay next sketch is, Caveman Olympics by Mike Schur. And the people start reading the sketch, and then whatever the joke of the sketch is, is sort of sprung. The first joke comes up and it dies, no one laughs even a tiny bit.

And what you know is that there’s nine more pages on that joke premise coming. And the first one didn’t work, and all you have is nine more pages of it. And what happens next is the sketch is dutifully read by the cast and the host. And the only sound in the room is the sound of like 110 people turning pages in a sheet of stapled paper. That’s the only sound, it’s just the like, shh, shh, over and over again.

And it is like, if you’ve ever wondered whether flop sweat is real, I actively flop sweated, so many times in those moments where I was like, I want to die. I want to get up and run out of the room screaming, because this is so painful. It’s all of these funny people. In my era, it was Will Ferrell, and Molly Shannon, and Traci Morgan, and Tina Fey, and Jimmy Fallon. The funniest people in the world, and all of your peers, all of the writers who were also the funniest people in the world. And you cannot make one of them laugh for one tenth of one second.

And as painful as that is, and I experienced it so many times. As painful as that is, what happens is if you can survive it, you get to the other side of it, and nothing bothers you. There’s literally no kind of institutional failure that can phase you anymore.

🐦 Tweet/s of the week

Narratives are powerful tools – and like all tools they can be used to either illuminate or mislead. An insightful tweet thread.

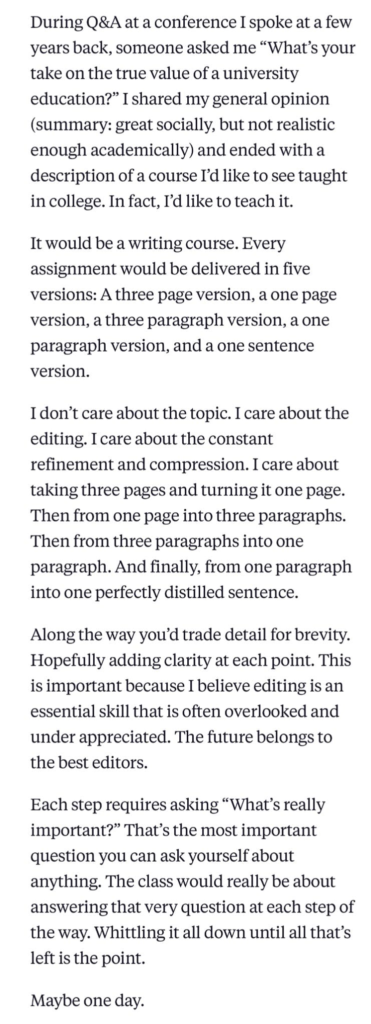

Summarising ideas well is a critical skill – one that I teach in my course.

Fascinating bit of history!

💬 Quote of the week

“You want a real Quick-Start Guide for how to live a good life? A guide so pithy you can have it tattooed on your arm with plenty of room to spare? Know thyself. Nothing in excess.”

– Michael Schur in ‘How to be Perfect’

🍿 Movie of the week

a. ‘Monica, O my Darling’ on Netflix

Once in a while you get a film that grabs your collar from the very first scene and doesn’t let you go till the end. ‘Monica, Oh My Darling’ is one such movie.

Directed by Vasan Bala, it unravels the story of a few (less than scrupulous) folks who get into trouble with a blackmailing damsel and decide to take a drastic step to solve the issue. But, as always, things don’t exactly go as per plan and much craziness ensues.

Watch it for the tight script (based on a Japanese novel ‘Burutasu No Shinzou’ by Keigo Higashino), quirky music and some fabulous acting, especially by the scintillating Radhika Apte.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the week.

Take care and stay safe.

Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash