Do you really know your own country?

This week’s book has been one of the most eye-opening ones I’ve read on India.

Book of the week

a. Whole Numbers and Half Truths by Rukmini S

Quick – answer whether these questions are True or False:

- Delhi has the highest rate of crimes against women in India

- India faces massive rural-urban migration

- UP is safer for women than many big states: NCRB report

- India has a large middle class

- You are a part of that middle class

If you answered ‘True’ for any of the questions above, you need to read Rukmini’s book.

I teach how to craft narratives with data and one of the things I used to take for granted was the ‘data’ part.

I mean, of course, in this age of abundant data, everyone has access to up-to-date, comprehensive and accurate information right?

A few months back, when I reviewed Brent Dykes’ ‘Effective Data Storytelling’, I wrote about the importance of ensuring that the data part of the equation is tied up and not taken for granted.

For, if you aren’t rigorous about getting the right data, you end up with narratives which may be divorced from the truth. Just like those True/False statements above.

But if those statements are not true, then what is the truth?

As per Rukmini’s book, the answer is, um, complicated. In a series of ten illuminating chapters she covers a wide range of topics about India – from crime to education to income, to eating habits to how we vote and how we fall ill – and deftly unveils a truer picture of India.

Here are some fascinating lessons from this eye-opening book:

1. In so many standard narratives, where we think we know the truth, the reality is much more complex and nuanced

a. For instance, take rural-urban migration.

The dominant narrative is that men from villages, mostly from north and east India are moving to cities in west and south India.

The reality is surprising:

Rural–rural migration, moving from one village to another, dwarfs rural–urban migration… Part of the reason that rural–rural migration is such a big part of the Indian migration story is because migration, overall, is overwhelmingly a female tale. Migration as it is usually understood in India is the movement of people (usually men) in search of jobs. But the truth is that migration in India is an overwhelmingly female phenomenon because of the sociological nature of marriage in the country, which tends to follow the norm of caste endogamy (marrying within one’s caste) but village exogamy (marrying outside one’s village). Women make up 68 per cent of all migrants in India and 66 per cent of them migrate because of marriage.

Of course we do have rural-urban migration, but not as much as we think it is prevalent (emphasis mine):

Most states—including those that are seeing the rise of strong anti-‘outsider’ sentiment—have an extremely low share of actual ‘outsiders’. Richer western and southern states might tell themselves that migrants from the north are flooding their states, but in reality just 9 per cent of people currently living in Maharashtra, 6 per cent in Karnataka and 2 per cent in Kerala were born outside the state.

These numbers were lower than what I expected. Though I surmise, they are perhaps still higher than historical numbers and I’d have liked to see that data here. Also, it would have been useful to see how migration patterns have moved in other countries – especially China – so that we have some more benchmarks.

b. Crime against women.

The dominant narrative here is ‘stranger-danger’. Entire cities are labeled safe or unsafe based on a few gruesome cases or statistics that are reported in the news. Where do these statistics come from? They come from a critical police document whose veracity we take for granted: the FIR (First Information Report).

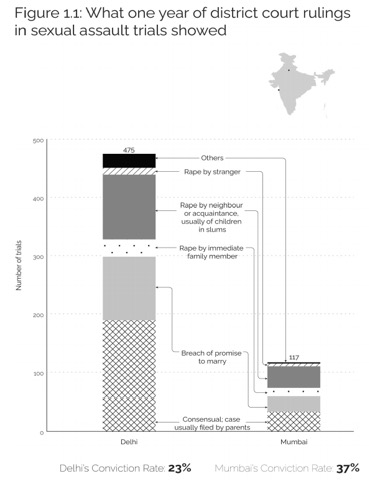

Rukmini decided to dig a bit deeper. In a powerful example of meticulous research, Rukmini examined all of the 600 judgements involving IPC Section 376 (which dealt with rape) from Delhi’s seven district courts for the year 2013.

Her findings are illuminating:

Assault by strangers is a small percentage of the total cases. The highest share is for consensual cases where the parents file a false case against the husband/boy for eloping with/marrying their daughter. It’s a sordid case of parental disapproval of inter-caste or inter-religious marriage. The details do not make for pleasant reading (emphasis mine):

In case after case, as well as in interviews with me, the behaviour of the families of these young consenting women was shocking: they arrived at the hotel or friend’s house the couple had eloped to and dragged them home, they beat and even injured the couple (in one case breaking the young woman’s spine), they threatened their own daughters and nieces with acid, they forced them to submit to invasive medical tests and in many cases, even to an abortion. Young women deposed about the suffering they faced at the hands of their parents—beatings, confinement, threats, being forced to undergo medical examinations, being forced to undergo abortions—even as they pleaded before the court they be allowed to stay with their husbands.

There are undoubtedly crimes taking place against the women here, but not the ones that are being prosecuted by the State.

Over years of journalistic writing, Rukmini has this well-honed ability to state all the facts plainly and then end with a gut-punch line like the one above. The book is peppered with several such lines.

2. For an emerging economy, India had a relatively robust statistical infrastructure

This surprised me:

The National Statistical Office (NSO) is in a sense the Indian Space Research Organisation, of India’s statistical landscape; a Nehruvian edifice that established India as a country that punched far above its weight in the 1950s and 1960s. While the foundation of the statistical system in India was laid down by the British administration, the new government of independent India took quick and decisive steps to establish a statistical architecture that was bold and ambitious.

Apart from this book, I’ve been listening to podcast conversations (this one with Pramit Bhattacharya and this one with Rukmini) and didn’t realise that India punched above its weight when it came to building its statistical infrastructure.

Unfortunately that edifice is under some pressure in recent years – hopefully things become better rather than worse.

3. But our on ground reporting, especially of crime, illnesses and other negative incidents, is poor

States with higher reported crime might actually be the ones doing a better job of ensuring full reporting, rather than being the ones that are the most unsafe, particularly for some types of crimes. People often use Kerala’s high rates of reported crime, particularly against women, to criticise the state, former state police chief Jacob Punnoose pointed out recently. ‘But what this shows is that with more female police recruitment, more women felt confident to approach the police. We should celebrate this’

The same logic applies to Covid data reporting. So we need to be careful before taking any government statistics at face value, especially those generated by administrative departments.

Engaging writing style

Apart from the several eye-opening insights in the book, I also enjoyed Rukmini’s clear, understated and pleasant writing style.

1. A sense of balance in the voice

At a time when there’s too much superficial, shrill and opinionated pieces masquerading as analysis, Rukmini’s work offers nuance, balance and an even tone. Consider for example this line about crime reporting:

Alongside acts of great bravery and hard work in trying circumstances, there is also extreme venality in Indian police forces. And, alongside genuine crime, there are also complex sociological forces that drive people into police stations, forces that have little to do with true crime. In short, FIRs alone say too little.

2. Infusing life into the data with anecdotes

The book is filled with several anecdotes and examples that help you put a face to the data. For instance Chapter 1 opens with the heartbreaking story of Seema and Sameer who eloped to get married and faced disastrous consequences. Or the fascinating portraits of the two Chennai-based women who share their nuanced thinking on who they vote for and why. Or even this delightful little anecdote in the chapter on work:

After passing her Class XII exams from a government school, Anju came to me for help for a job. What sort of work do you want to do? I asked her. One in which I have to wear a salwar-kurta and carry a file to office every day, she told me.

In so many cases, the data comes out alive with these real-life examples.

In a later interview, I realised how conflicted Rukmini was about the addition of the ‘human interest story’ to ‘humanise’ her numbers. She says that her reticence comes from the worry that the addition of a human story can become a formulaic trope of its own.

I get that… but in this book, I felt that the stories added a lot of colour and helped me ‘get’ the data better.

3. Investigative journalism to suss out the truth behind data

As an ex-field reporter, Rukmini shares quite a few war stories from her experience. None of them are more striking than the ‘Meow meow’ drug story.

In 2013-14, the Mumbai police started making a lot of arrests under Section 328 of the IPC (causing hurt using a poisonous substance) for people selling a narcotic substance called mephedrone (street name: meow meow).

Over the next two years, as these cases came up for hearing in court, what do you think was the conviction rate? 40%? 60%?

It was zero.

All the accused were acquitted.

What was happening here? Based on Rukmini’s investigation:

- The drug mephedrone was available cheaply and easily in Mumbai and was being peddled by many dealers

- But it was not yet a banned substance under the stringent Narcotics Act, despite pleas from the Mumbai police to the Central Agencies

- So the Mumbai police got creative. They booked the peddlers under a different law – Sec 328 of the Indian Penal Code

- That section was meant for people indulging in food poisoning (where the victim/s would be unaware) and not for drug dealing (where the buyers are aware and consenting)

- Since they were applying the wrong section, the police knew that they would not get any convictions in court. But they took the cynical view that “at least we’ll put them in for the duration of the case”

- According to Rukmini, “IPC 328 is a non-bailable offence; the accused in the cases I saw spent between one year and twenty months in custody. An analysis of their names shows that 119 of the 148 acquitted were Muslim.“

She ends this section with this cautionary para:

For anyone looking at crime statistics of the time, as I was for what began as unrelated research on sexual assault FIRs in Mumbai, it would have seemed as if the city was awash with incidents of poisoning, mostly committed by Muslims, and the courts were failing victims. What would have remained hidden between the lines is that forming any assessment of India from police reports or from media reports of them is an exercise in futility—or worse, in deception.

You’ve been warned: Take official statistics with a massive pinch of salt.

What could be better

In some cases I felt the book could do with more norms – historical and global. For instance this portion:

The bulk of India’s workforce is engaged in the ‘informal’ sector, meaning that they have little in terms of job protection, benefits and social security. Seven out of ten workers in the non-farm sector are in informal employment, seven out of ten salaried workers in jobs with no written contract and over half in jobs that give them no paid leave or social security benefits.

I’d like to know what this number was earlier (maybe across the last few decades?) and also what are relevant global benchmarks. It would also be useful to see whether the share of formal workers has changed in certain sectors (e.g. the gig economy) over the last few years.

Such quibbles aside, this is a fabulous book. If you really want to know your country – and why wouldn’t you – you should read Rukmini’s book.

Podcast episode/s of the week

a. Rukmini sees India’s multitudes (Jan-2021) and The Importance of Data Journalism (Oct-2020) – Podcast interviews with Amit Varma

If you really want to get to know someone’s work, you can:

– Go on a multi-day trek with them

– Work with them in a high-pressure job for several years

– Play sports with them regularly, or

– Just hope that they come as a guest on Amit Varma’s podcast

Over these two conversations (one in Oct-2020, which became the trigger for the book, and another recently, after the book was published), you get to know Rukmini the person and how she approaches her work.

The fact that she wrote the book in about 5 months during the lockdown with two small kids at home… makes me want to bury myself.

More than anything though, I was struck by her warmth, even tone and genuine empathy for all of her subjects.

a. The Truth about Hansel and Gretel by Cautionary Tales

Some audio narratives are so immersive and gripping that you get goosebumps listening to some parts. It’s the rare narrative that does it several times in the same episode.

I was blown away listening to this utterly fascinating story about the ‘real’ truth behind the story of Hansel and Gretel. I was listening to it while doing house chores and on several occasions, I just stopped in my tracks, gripped by the narrative.

This episode belongs in a Storytelling Museum. What narration by Tim Harford.

Tweet/s of the week

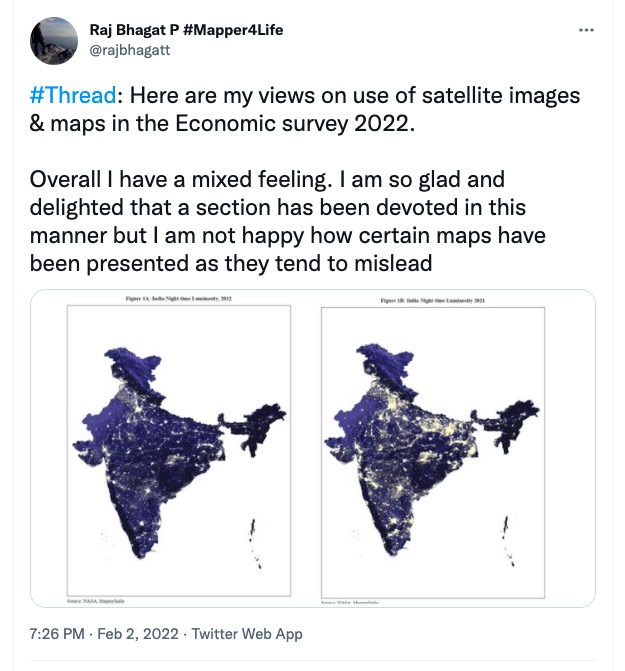

The recently released Economic Survey made a big deal of the Night-Time Lights (NTL) maps of India and how those have changed over the last decade.

This thoughtful analysis by a maps-geek celebrates the inclusion of a new form of data, but does raise some concerns on the methodology.

Quote of the week

“The fool tells me his reasons; the wise man persuades me with my own.”

– Aristotle

Movie of the week

You are living a dream life. An American tech geek, working in a high-tech job, you help your country fight cyber war against enemy nations. You have a fun group of smart and driven colleagues. You are working and living in sunny Hawaii with your doting girlfriend and having a great time exploring its stunning locales. You are paid really well. And oh, you are 29.

What will make you give up ALL of that to live the rest of your life running away from your own country? To be under the threat of being killed or tortured? To lose everyone you love?

Edward Snowden is of course that incredibly brave guy – and this movie does a great job of telling his story.

Bonus: Once you’ve seen the movie check out this real-life interview of him in the same hotel room where a chunk of the movie is based.

Video of the week

a. Post Pandemic Traumatic Stress by Foil Arms and Hog (2:24)

How will we cope with the memories of 2020-2021 in the decades to come? The Irish lads decide to take a dire look.

Their forecast: It’s not going to be pretty.

b. Speaking after MLK Jr. by Key and Peele (3:16)

You’re all set for your big speech. The script is tight, you’ve rehearsed several times and the crowd is massive.

The trouble: they’ve just heard Martin Luther King Jr. deliver one of the greatest speeches of all time.

In this hilarious thought experiment, Key and Peele mull what its would have been like to follow the Reverend Dr King.

Keegan-Micheal Key nails the frantic, panicked delivery.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the week.

Photo by Joshua Olsen on Unsplash