How Jaws was made (almost) without the shark

Last weekend we celebrated the 50th wedding anniversary of my in-laws, in Goa. It was a large group of around 29 of us, and everyone had a memorable time.

One activity which we all loved was photo-housie (or photo bingo). Some of you might remember the ‘story housie’ game that I had written about earlier. This was similar, except, instead of stories, each number corresponded to a photo shared by a relative. When the number was announced, apart from marking it on our housie cards, we got the photo-sharer to recount the story of the photo. It was a lovely walk down memory lane.

Thanks for reading The Story Rules Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And now, on to the newsletter.

Welcome to the one hundred and twenty-third edition of ‘3-2-1 by Story Rules‘.

A newsletter recommending good examples of storytelling across:

- 3 tweets

- 2 articles, and

- 1 long-form content piece

Let’s dive in.

𝕏 3 Tweets of the week

One of the OG writers on the internet endorses the need to do your own writing.

And the AI-God himself agrees – “I never use it for writing drafts or posts”.

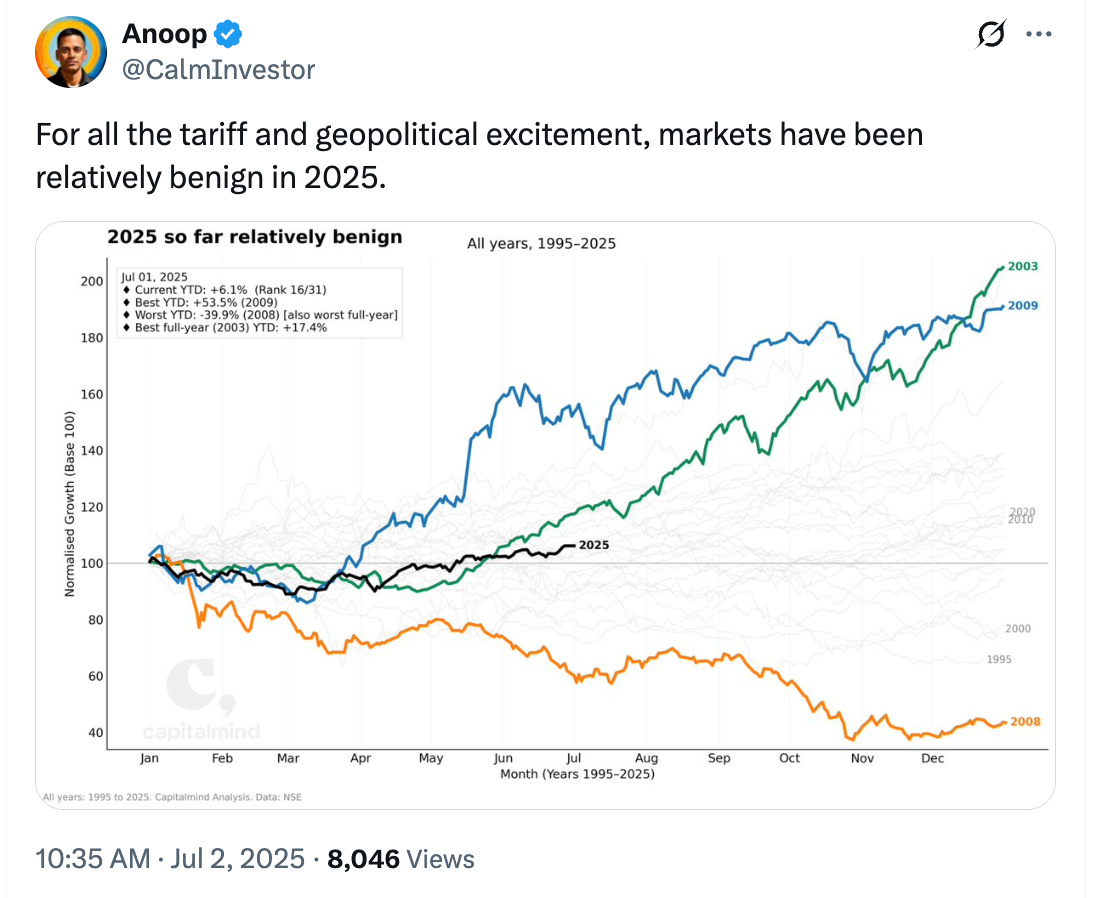

Fascinating chart showing the market movement across 30 years. Smart use of visual highlighting to make the outliers (and 2025) stand out.

📄 2 Articles of the week

a. ‘The Audience Shortcut: How the Right People Paying Attention Changes Everything’ by Nathan Barry

Nathan Barry is the uber-successful founder of the email platform Kit, and in this post shares some thoughts on what led to his success as an content-driven entrepreneur.

He had his realisation when one of his startups succeeded after a string of earlier failures:

OneVoice made $50,000, which was life-changing money.

But what surprised me was that the difference wasn’t the idea, the funding, or even the execution.

It was the audience.

Barry’s (not exactly earth-shattering) insight was to identify the right influencers for the product:

Initially, I didn’t know how I’d reach my first users. Parents of special needs children were scattered and impossible to reach efficiently.

The breakthrough came when I asked: “Who do these parents already trust and listen to?”

The answer: Speech-language pathologists (SLP). These professionals were concentrated, easy to find, and each influenced dozens of families weekly.

I gave 50 free licenses to SLPs, positioning it as “seeking professional feedback” rather than trying to sell them the app directly. They were thrilled to give detailed feedback, which I quickly implemented.

His advice – when it comes to building an audience, don’t go after quantity. Go after quality:

The recipe is simple: Build an audience, not a crowd.

What’s the difference?

A crowd is people paying attention to you.

An audience is the right people paying attention to you.

And be careful of growing too fast:

Your audience should expand at a pace that supports your dreams, not crush them.

Joe Rogan often mentions how fortunate he was that his fame grew gradually over decades. This allowed him to develop at a pace he could handle, instead of being crushed by sudden celebrity.

Aim to be useful, not to attract attention for the sake of it:

People don’t follow you because you’re special.

They follow you because you’re useful.

Building an audience isn’t shouting “look at me!” It’s asking “How can I help?” This simple shift transforms what feels like begging for attention into an act of service.

In this post, Ashish shares with us three types of roles that would thrive in the age of AI (by referring to an article published in the New York Times):

Capps gives us three answers, which I’m going to dub the holy trinity of job searches in the age of AI:

- Trust

- Integration

- Taste

Under the trust dimension, apart from the need for quality auditors for AI output, Ashish talks about the need for AI translators:

When I teach statistics, I often tell my students that their most underrated skill as a statistician is being able to speak the English language well. If you tell me, for example, that you’ve run an experiment and rejected the null because the p-value is 0.003, I’ll be (mostly) fine with it. But that’s because I speak Statisticese.

Not everybody does! And so you have to, as a statistician, also be able to translate your work so that ordinary mortals can understand just what the hell is going on. This will be applicable to a lot of the things that AI will do in the future as well – you will need, Capps says, AI translators, just like you need statistics translators today.

Personally, I am very interested in the third ingredient, which is taste:

Veo3 can come up with twenty different clips, all of them being very, very good. But who chooses which clip actually makes it into the final product? On what basis?

How do I know that this clip here is better than that clip there? You may not be the creator of the clip, but is the Chooser of the Best Clip an even more important job? Can writers become article designers? Can singers become song choosers?

This isn’t mentioned in the article, but can they help other people develop taste better? In a world with infinite choices and limited time, developing taste itself becomes a very important thing.

🎧 1 long-form listen of the week

a. ‘The Shark That Ate Hollywood’ on Cautionary Tales by Tim Harford

This episode features the fascinating story of the making of the super hit movie Jaws and is a great example of how creativity thrives under constraints.

The movie was based on a bestselling book and the producers wanted a capable director at the helm of affairs.

I love how Harford introduces the legendary director of the movie by revealing his name at the very end of the paragraph:

(Producers) Zanuck and Brown were excited about a precocious young talent they’d recently worked with. But did he have the maturity and authority to keep such a movie from careering off into disaster? The kid can bring visual excitement to it, said Zanuck, and will give him the support he needs. The kid was Steven Spielberg.

Spielberg had been terrified reading the book and so wanted the movie to be as realistic as possible.

…he wanted audiences jumping out of their cinema seats as if they’d been hit with an electric cattle prod.

And that wasn’t going to happen with some scale model shark and actors on a sound stage in front of a blue screen. Jaws, the movie, would get laughed out of town. Spielberg insisted they film on the actual ocean, and that the shark be as believably scary as possible.

They tried filming with real sharks, but that was a disaster. So instead Spielberg decided to create a giant mechanical shark. He got three replicas of it created (and named each ‘Bruce’, after one of his lawyers!).

There was only one issue though: While each Bruce worked well in freshwater, it failed badly in seawater:

When things got really bad, Spielberg called his mechanical actors Great White Turds. Each Bruce had performed well in freshwater tests, but on the rough ocean and in corrosive saltwater, everything began to fail. The lifelike neoprene shark skins soaked up water, adding vast weight to the model.

In a set filled with movie stars, the most temperamental artist was… the shark.

The shark came arching out of the water. Only it rose tail first, as if mooning Zanuck and his crew. This animatronic prop would have been funny, had so much money and so many reputations not been in serious jeopardy. ‘Jesus Christ’, said movie producer Zanuck, ‘we’re making a picture called Jaws, and we don’t have the fucking shark.’

And guess what—the script was filled with shark scenes:

The script was filled with shark, he lamented. Shark here, shark there, shark everywhere. The young director filmed what he could. Interior scenes, scenes on the docks, scenes on the beach, street scenes. All the time, hoping Bob Matty (the guy making the mechanical sharks) would perform a miracle, but deep down, fearing that his burgeoning directorial career was about to sink without trace.

The episode then also details other challenges that came up in shooting, including a simmering feud between two of the leading actors, disgruntled crew, and irritated locals.

But guess what—sometimes we become more creative when we are under a lot of pressure and constraints:

…the constant delays gave him (Spielberg) room to reconsider. It was good fortune that the shark kept breaking, says Spielberg, because I had to be resourceful figuring out how to create suspense and terror without seeing the shark itself. The script went through several iterations, but what made it to the screen was the version Spielberg hammered out at night in the house he shared with Carl Gottlieb on Martha’s Vineyard.

The key change: the movie communicated the shark’s threat without showing the shark. A superb take on the ‘show, don’t tell’ storytelling principle.

Don’t show the shark, show the terror on people’s faces. Use ominous music that builds an impending sense of doom. And then, when people least expect it, let the shark make its appearance.

The audience loved it (emphasis mine):

Test audiences loved it, and the critics were bowled over. A problem-plagued film turned out beautifully, wrote Variety. The critics were especially impressed by Spielberg’s restraint in not showing the shark for the first 82 minutes of the film, making the unseen beast all the more terrifying for its invisibility.

The lack of explicit carnage also had the added bonus of making Jaws a PG movie, meaning whole families could go see it and widening its box office potential. Summer was, until then, a dead zone for new releases, but Jaws upended that. It turned a profit just two weeks after opening in June 1975, and by Labor Day, it was the most successful motion picture in history

So the next time you face constraints, do your best to resolve them; but if you cannot, then instead of complaining, amp up your creativity!

That’s all from this week’s edition.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash