#SOTD 58: The importance of historical context (and analogies!)

#SOTD 58: The importance of historical context (and analogies!)

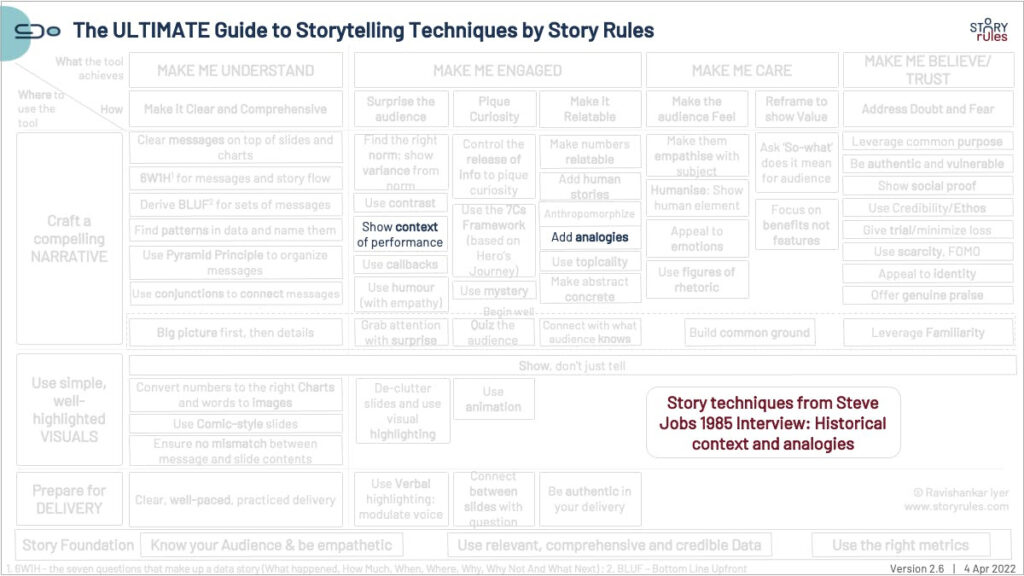

In Monday’s #SOTD, I profiled a brilliant Steve Jobs interview from 1985.

Yesterday’s storytelling theme was Steve’s ability to discern patterns and provide concrete examples.

Today’s theme: Jobs’ ability to understand historical context and come up with relevant analogies from the past

You get the impression that Jobs is a brilliant, almost obsessive student of his field. He knows the historical context of the industry as well as general business history. Frequently he launches into historical analogies of what makes the computing revolution special.

For instance, David is sceptical of home users having to invest $3,000 in 1985 for something which did not have a lot of utility then:

David: Then for now, aren’t you asking home-computer buyers to invest $3000 in what is essentially an act of faith?

Steve: In the future, it won’t be an act of faith. The hard part of what we’re up against now is that people ask you about specifics and you can’t tell them. A hundred years ago, if somebody had asked Alexander Graham Bell, “What are you going to be able to do with a telephone?” he wouldn’t have been able to tell him the ways the telephone would affect the world. He didn’t know that people would use the telephone to call up and find out what movies were playing that night or to order some groceries or call a relative on the other side of the globe. But remember that first the public telegraph was inaugurated, in 1844. It was an amazing breakthrough in communications. You could actually send messages from New York to San Francisco in an afternoon. People talked about putting a telegraph on every desk in America to improve productivity. But it wouldn’t have worked. It required that people learn this whole sequence of strange incantations, Morse code, dots and dashes, to use the telegraph. It took about 40 hours to learn. The majority of people would never learn how to use it. So, fortunately, in the 1870s, Bell filed the patents for the telephone. It performed basically the same function as the telegraph, but people already knew how to use it. Also, the neatest thing about it was that besides allowing you to communicate with just words, it allowed you to sing.

David: Meaning what?

Steve: It allowed you to intone your words with meaning beyond the simple linguistics. And we’re in the same situation today. Some people are saying that we ought to put an IBM PC on every desk in America to improve productivity. It won’t work. The special incantations you have to learn this time are “slash q-zs” and things like that. The manual for WordStar, the most popular word-processing program, is 400 pages thick. To write a novel, you have to read a novel—one that reads like a mystery to most people. They’re not going to learn slash q-z any more than they’re going to learn Morse code. That is what Macintosh is all about. It’s the first “telephone” of our industry. And, besides that, the neatest thing about it, to me, is that the Macintosh lets you sing the way the telephone did. You don’t simply communicate words, you have special print styles and the ability to draw and add pictures to express yourself.

Fascinating analogy between the telegraph-telephone and the IBM PC and Macintosh.

It’s not just stuff related to computers. Jobs also shares the reason for Silicon Valley becoming the world’s premier tech hub:

David: How did Silicon Valley come to be?

Steve: The Valley is positioned strategically between two great universities, Berkeley and Stanford. Both of those universities attract not only lots of students but very good students and ones from all over the United States. They come here and fall in love with the area and they stay here. So there is a constant influx of new, bright human resources. Before World War Two, two Stanford graduates named Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard created a very innovative electronics company – Hewlett-Packard. Then the transistor was invented in 1948 by Bell Telephone Laboratories. One of the three co-inventors of the transistor, William Shockley, decided to return to his home town of Palo Alto to start a little company called Shockley Labs or something. He brought with him about a dozen of the best and brightest physicists and chemists of his day. Little by little, people started breaking off and forming competitive companies, like those flowers or weeds that scatter seeds in hundreds of directions when you blow on them. And that’s why the Valley is here today.

Having an interest in the historical context of your industry (including its geography) is very useful in being able to come up with the right analogies for present day events.

#SOTD 58