#SOTD 72: Use the right metrics and norms (Economist article)

#SOTD 72: Use the right metrics and norms (Economist article)

Among other criticisms, there are two primary ills that advocates of free-market economic policies have to contend with:

– Crony capitalism (regulatory capture)

– Dominance of big business houses

But how do we know a society is suffering from a particularly acute case of the above two ills?

We use the right metrics for the job.

A recent Economist article on the state of the Indian economy dealt with this issue (I reviewed the piece in my recent Saturday email).

In the article, the writer initially talks about how large business houses in India have massive investment plans:

Big companies with large cashflows are looking to change this. Saurabh Mukherjea of Marcellus, an asset manager, calculates that India’s top 20 firms earn 50% of corporate India’s cashflows. They are making money fast enough to take risks with their earnings instead of having to borrow to excess. The ambitious giants include conglomerates – Adani (energy, transport), Reliance Industries (telecoms, chemicals, energy, retail), Tata (IT, retail, energy, cars) – and more focused giants such as JSW (mainly steel).

Those four firms alone plan to invest more than $250bn over the next five to eight years in infrastructure and emerging industries; in doing so they intend to develop local supply chains, which fits with government goals. Mukesh Ambani of Reliance says he will cut the price of green hydrogen to $1 per kilogram by 2030, for instance, from about $5 today. Tata is rolling out battery plants, electric vehicles and semiconductors. These are huge, risky bets that few other firms would dare take.

Naturally if there is talk about big business, there is the attendant risk of cronyism and dominance by large players (which may crowd out smaller players).

The article addresses that in the next two paras in a nifty manner (emphasis mine):

There are worries about excessive corporate power, monopolies and, in some cases, cronyism. If the firms accrue yet more economic power through their investments, such concerns will surely grow.

At the moment, though, the ratio of those four firms’ profits to national GDP is 0.7%, half the equivalent ratio for the four tech giants which are currently America’s biggest companies. The government seems happy with big business, given its high reinvestment rates.

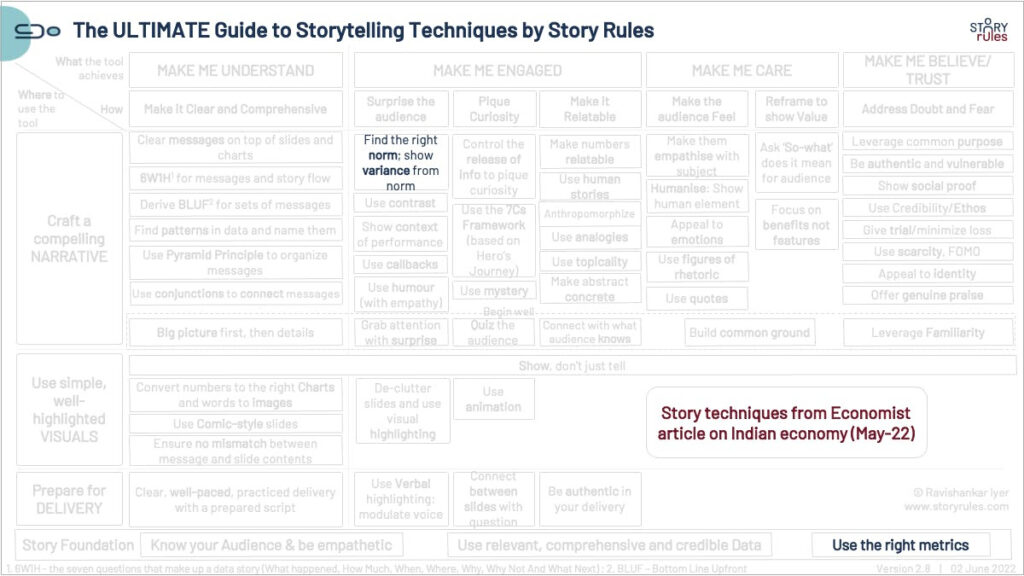

What The Economist does here:

– Clearly defines a metric (‘ratio of profits to GDP’) to measure a concept that is usually discussed in an abstract manner

– Uses the right norm (comparing it with the same metric for the US)

– Implies another norm when it says “government seems happy with big business, given its high reinvestment rates”. The implication: In a lot of such cases of dominance, firms tend to distribute profits as dividend, instead of reinvesting in growth.

When dealing with abstract issues, try to quantify it with the most appropriate metric and then look for the right norms to compare that metric with.

#SOTD 72