Will nation states give way to ‘Decentralised countries’?

Headlining today’s edition are a couple of brilliant pieces that predict the end of the ‘nation state’ and the prospects of blockchain-driven Decentralised Countries to replace them.

Incidentally, today’s email has turned out to be a crypto-special one – I’m sharing some of the best storytelling I’ve come across in this domain.

(In case you missed my previous email, I have changed for format of ‘Story Rules on Saturday’. Now the Saturday emails would consist of my weekly content-recommendations. Expect the emails to get shorter – and crisper!)

Articles of the week

a. The End of Nation States by Tomas Peuyo and The Decentralised Country by Mario Gabriele, The Generalist

Whenever there is a fundamental new innovation, storytellers are presented with a key task: to make sense of the innovation and discern – is this like something we have seen in the past?

In the last twenty-five odd years, disruptive innovation led by the internet and recently, blockchain based technologies has completely upended our world.

Even as humankind is benefiting from all this innovation, some thinkers are consumed by a key question: How to place these new developments in historical context? What is this animal really?

And when good storytellers try to make sense of these seemingly unprecedented technologies, they have one main tool in the hands: the historical analogy.

They ask themselves: Is this like the invention of electricity? Or the transport revolution brought about by the exploitation of crude oil reserves? Or does it go further back, being similar to breakthrough inventions like the steam engine?

Turns out it goes even further back.

First up, Tomas Pueyo, one of the world’s most read bloggers (his viral article at the beginning of Covid received 40M+ views).

Tomas’ article titled ‘The End of Nation States’ (dated Sep-2021) gave me a new perspective on how the Blockchain (combined with the internet) would be a once-in-a-generation innovation that will fundamentally change things around us.

I loved how Tomas began his piece, with an attention-grabbing scenario:

It’s 2050. The US government just defaulted on its debt.

It’s not meeting its social security payments. Hospitals are going down: they can’t operate without Medicare and Medicaid income. Old people line up outside the hospitals. Hospitals don’t service them. They can’t afford it. There’s a run on the banks that held too many dollars. They are collapsing. All the governments around the world caught with too much US debt are defaulting. Those with their savings in dollars have been wiped out.

They are looking at the last few decades of their lives like an empty ravine.

What happened?

The Internet and Blockchain.

And then puts forth his thesis (emphasis mine):

Every time a new information technology is discovered, our power structures change.

Speech allowed chiefdoms.

Writing allowed kingdoms, empires, and churches.

The printing press replaced the Catholic Church and feudalism with the nation-state.

Broadcasting made totalitarianism viable by allowing the efficient transmission of propaganda.

This time we have not one but two new information technologies: Internet and Blockchain. How will they undermine the nation-state?

The key point? The Internet and Blockchain are fundamental innovations in the same league as language, writing and the printing press.

Let’s move to the second article now. It’s written by Mario Gabriele, founder and editor of The Generalist, a newsletter and community focused on tech writing.

Tomas spoke about the changes wrought by the printing press. And Mario adds that these took centuries to play out:

The French nation rose in 1789, more than three centuries after Gutenberg’s v1. Italy took nearly another hundred years.

A few factors contextualize this interlude. For one, it took time for publishing production to ramp up and for those works to spread across the continent and around the world. In the final 60 years of the 15th century, Anderson notes that about 20 million editions of the Gutenberg Bible had been printed. Over the following century, 200 million were produced. Production of books per half century grew from 12.6 million in 1475 to 640 million over the following three hundred years.

Secondly, literacy improved gradually. Four hundred years after Gutenberg’s 1440 innovation, only about half of the English and French populaces could read. In Russia, only 2% were literate.

Finally, recalibrating fundamental beliefs about time and existence is usually not easily made. Even today, many “secular” nations are heavily influenced by preceding spiritual doctrines.

Using contemporary framing, we can say that the printing press took time to scale and had a relatively long consumer adoption cycle.

So ok, the The analogy of the printing press is explained in richer detail when you consider vernacular languages. Here’s Tomas:

Before the printing press, people in Europe talked mostly with their neighbors in their very local vernacular (languages like French, German, Spanish), while the Catholic Church spoke a universal Latin that gave them power. As the printing press started publishing in whichever local vernacular was most widely spoken—i.e., that of the biggest cities—it accelerated Latin’s demise while the local vernaculars of the biggest printing centers slowly grew in popularity until they became national languages that shared ideas and identity across geographies. This is what eventually led to the rise of nation-states.

And then you have this from The Generalist’s piece which connects the analogy:

…blockchains have also “vernacularized” economics. That is meant literally — it has empowered and elevated the formation of new, internet-native economies.

We can lean on analogy to clarify this point. Traditional economies are spiritually akin to the “sacred languages” that humans once presumed had special access to the truth. Fiat currencies, and associated instruments, are conceived and controlled with a top-down structure and are seen as superior to “vernacular” monies, holding special value. (Often with good reason).

Currencies like bitcoin are the internet’s vernacular money and have historically been viewed with similar condescension. To the conventionalist, bitcoin or Ethereum is not “real” money, nor has it created a “real” economy. Increasingly, we see that position challenged to breaking point as cryptocurrencies rise in value and popularity.

Finally, here’s how Tomas concludes his piece:

We know how this ends. It happened five centuries ago, when the Catholic Church tried to suppress the printing press instead of reforming itself. It failed because it couldn’t stop the avalanche of technological progress. Within decades of the invention of the printing press, it had splintered, never to return to its glory days again.

For nation-states moving forward, there are only two paths. The first one is totalitarianism. They can do like China, split from the rest of the world, and control everything that happens internally, at the cost of destroying development and erasing individual freedom.

The other alternative is choosing freedom, which means competition between many of the 195 countries that exist today, the impossibility of collusion between them, and the unavoidable result of the demise of the nation-state.

The only question left is: what will replace nation-states?

The Generalist seems to have a perspective:

First, we may see DeCos lobbyists seek to influence favorable legislative change. Some may even run for elected office. These should be seen as intermediary steps designed to remove physical world impediments.

If unable to gain traction in the existing political system, some budding DeCos may seek to settle or win tracts of land themselves in which they can self-govern. Attaching themselves to a specific territory may come at a cost, though. Not only does it reduce the potential scale of a DeCo since it is grafted onto an exact physical location with finite space, but it also introduces necessary low-value work. Does a DeCo want to spend time and resources planning upgrades to its municipal sewage system? Or would it be better off allowing that relatively solved problem to be handled by a denuded physical world legislative body?

If we believe that value will increasingly accrue to the digital world over the physical one, it seems that DeCos that devote themselves to the former will capture most power. In that respect, I think the most influential DeCos touch as little land as possible, and ideally none. Rather than outright exterminate the concept of nations, DeCos will sit above them, using their social and financial capital to guide terrestrial policies. At various times in human history, states and empires have allowed themselves to be jockeyed by religious organizations that professed unique powers; DeCos should be able to make a similar claim.

By taking this approach, DeCos retain the ability to draw from the broadest possible constituency, humanity, and focus their efforts not on the world of bricks and mud but bits and pixels.

And if you think such an eventuality might be sometime in the distant future, here’s the final point made in The Generalist piece:

It will take time for old structures to fall, and yet — it all may arrive faster than we think. Today, Singapore is one of the most successful sovereignties in the world, with the fourth-highest GDP per capita, robust infrastructure, a strong state education system, and one of the best healthcare systems in the world. It only surfaced as an independent polity in 1965, just 56 years ago.

Half a century may be long enough to see the coronation of a true DeCo.

Fascinating stuff.

b. What we’ve learnt from cricket’s second Covid year by Sambit Bal

A key skill in storytelling is to look at disparate pieces of information and discern overarching patterns. Sambit Bal (editor-in-chief at Cricinfo) does a skilful job of doing that in this 2021 annual review.

One interesting idea he proposes: to get the top three teams (India, England and Australia) to field multiple teams:

Countries fielding two sides simultaneously is an idea whose time has come: those with deeper talent pools – India, England and Australia to start with – must consider, or be persuaded to consider, the idea.

The benefits are self-evident. It will create more opportunities for smaller teams in a slightly more even playing field. Teams like Ireland, Afghanistan and Zimbabwe, who rarely get to play the top sides, will be the obvious beneficiaries, but the idea can extend to other teams too: Bangladesh are in a white-ball slump, Sri Lanka are rebuilding and could do with more competitive cricket, and for teams like Scotland, Netherlands, USA or even Nepal, who mainly play each other, a few chances to test themselves against top-quality players outside of the World Cups will be priceless. There can’t be a less contentious way for the Big Three to share their wealth. Their own fringe players will also be grateful for the international caps.

Podcast episode/s of the week

a. Crypto Wars by Business Wars

Continuing on the crypto theme, this is the most entertaining history of the crypto-economy you can listen to.

I love how they are able to make this series so engaging by:

– Deep-diving into the key moments – in a story that plays out over more than a decade

– Giving so much rich colour and personality to the key people involved

– Ensure that the story moves ahead at a fast pace, despite not skipping over key details

Listen to this series. You will be entertained, learn about crypto and also learn how to tell a good story!

b. ‘On the Contrary’ by India Development Review: The purpose of education: learn, do, become

I’m always on the lookout for good Indian podcasts. I stumbled across this one hosted by the venerable Arun Maira (ex-BCG Chairman and former Member of the Planning Commission), and featuring interviews with experts on various public policy issues.

This episode on the Purpose of Education has two accomplished thinkers (and doers) – Atishi Marlena (one of the drivers behind Delhi’s school education revolution) and Pramath Raj Sinha (ex-Mckinsey, Founding Dean of ISB and one of the founders of Ashoka University and currently Chairman of Harappa Education).

I loved the nuanced, insightful responses by both Atishi and Pramath. Here for example is a thought-provoking point by Atishi:

I think that the process of learning is content agnostic; it does not matter what specific content you teach. Whether I teach the history of India, whether I teach the history of Great Britain or I teach the history of Sumatra and Java—what we need for children to understand when we are teaching history is the process of social change, how societies change, what brought about that process of change, and who were the people who pulled the levers of change; this is what we need them to understand.

A minor quibble: While the topics and guests are impressive, Arun Maira comes across as surprisingly formal in his delivery – I felt the tone could be more conversational.

Tweet/s of the week

Stanley has written a tweet thread with simple and actionable tips to increase your book reading time. I liked this one:

Don’t just read in bed. Make time during the day. If reading is important to you, don’t do it only when you’re waiting to go to sleep. As a rule of thumb, the number of minutes you read per day is the number of books you read per year. Why not aim for an hour a day? 60 books!

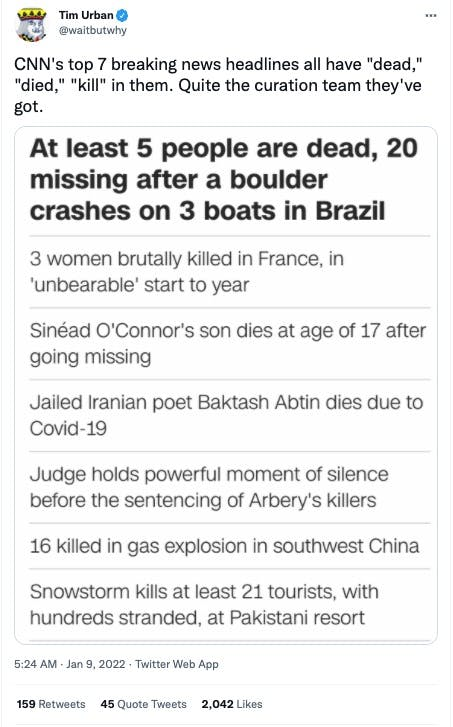

Sad but true. News media’s propensity to ‘afflict the comforted’ can lead to a highly skewed representation of the world.

Quote of the week

“Writing is 50% thinking, 5% typing, 45% deleting the bad parts.”

– Morgan Housel

Movie of the week

a. ‘Don’t Look Up’ on Netflix

I was wowed just looking at this movie’s cast: Leo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Jonah Hill, Cate Blanchett, (The!) Meryl Streep… all heavyweights. The trailer was intriguing and I’m glad I decided to see it – the movie is a fabulous watch.

The premise is fascinating: A couple of astrophysicists discover a comet that is on a collusion course with Earth… the impact date being just 6 months away. You’d expect a global galvanisation of efforts on a war footing to divert the comet.

Instead, the world reacts… with indifference. Funny memes are created, ad-hominem attacks are made on the scientists and a large section of the population (including politicians) believe that the comet is, wait for it, fake news.

Drawing several parallels to present-day events, this dark satire holds a (black) mirror to society.

A quibble: This is a Hollywood movie, so while the problem is a global one, the movie gives the impression that the only country which can do anything to solve this issue is the US. In a disappointing scene, a rocket being jointly built by Russia, India and China explodes before takeoff itself. So much for a global response.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the week.

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash