Storytelling lessons from the world’s 3rd Richest Man

Warren Buffett may be one of the most envied guys on the planet – for his unparalleled wealth, that magic touch in picking stocks, and decades of consistent outperformance.

But he also has a most unenviable task: to write a 12-page annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders – a document that is eagerly awaited by the investing world at large.

Why should that be so difficult you may ask? Consider the facts.

75 companies, 365 days, 12 pages

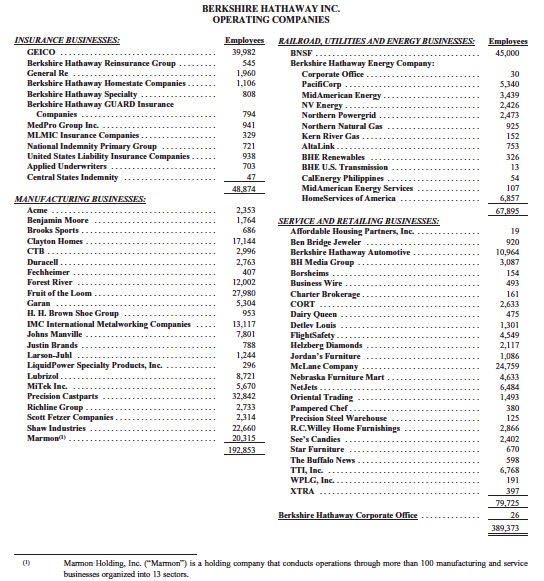

Berkshire Hathaway is not your normal holding company. It’s the world’s third biggest by revenues ($247B) that owns an incredibly diverse set of companies – seventy-five entities across insurance, manufacturing, utilities and services (as he puts it, making everything from ‘lollipops to locomotives’). Take a look at this list below:

Now imagine writing a detailed document that talks about all these varied enterprises, and the overall economy, and the impact of key accounting/tax policies and the future outlook … and (here’s the really difficult part): making sense of it all to the average shareholder.

Not an enviable task? That’s what I thought.

Buffett’s approach: Storytelling

Warren Buffett employs two masterful storytelling techniques to take on this daunting task:

- Get the ‘Big Story’ right (think of this as the basic pizza base and sauce)

- Embellish the Big Story with key story elements (think of these as the toppings that add flavour, texture and colour to the pizza)

Let’s look at each one in turn.

I. Getting the Big Story right

I had earlier blogged about Jeff Bezos (just two steps higher than Mr. Buffett on that Forbes list) who used the ‘Pyramid Principle’ in constructing Amazon’s succinct annual letter. Not surprisingly, Buffett’s approach is similar.

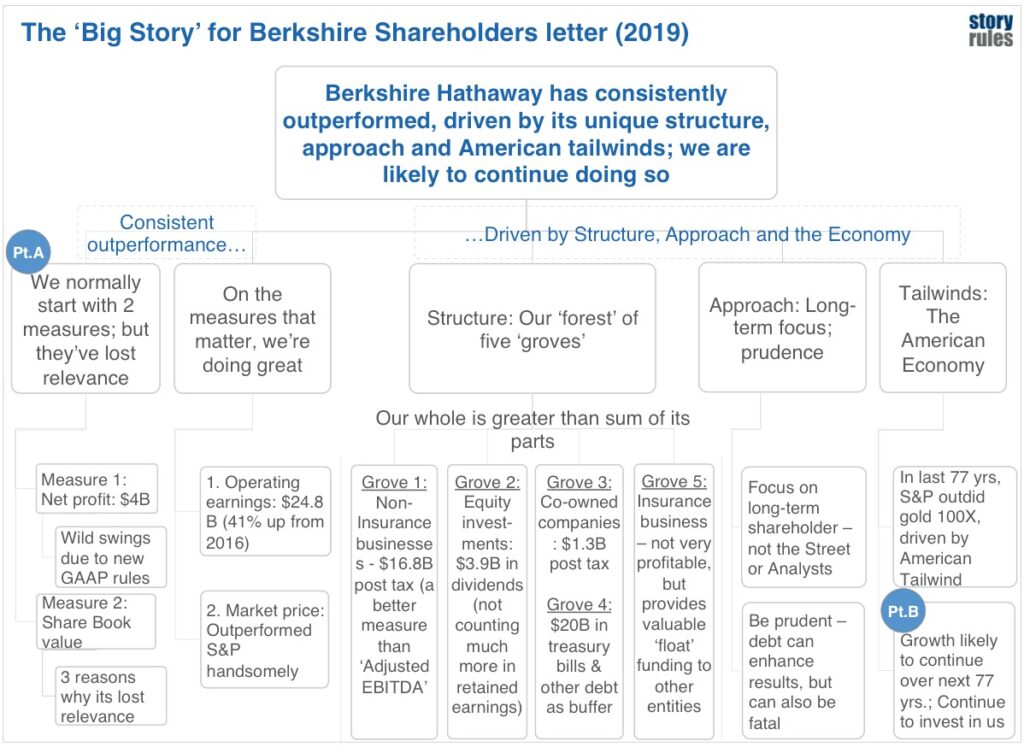

While he takes some liberties with the format, the broad flow is clear, and he makes three key points:

Main message: Berkshire Hathaway has consistently outperformed, driven by its unique structure, approach and American tailwinds; it is likely to continue doing so

- Berkshire has consistently outperformed the competition

- We normally use two measures to state this (net profits and Share Book value) – but both have lost relevance

- On the measures that matter however, we are doing great

- There are three key reasons for our success

- Our unique structure: We are a ‘forest’ of companies with five ‘groves’ – where the whole is greater than the sum of parts

- Our approach: Long-term shareholder oriented; prudence in use of debt

- The American economy tailwind: which has propelled us for the last 77 years and will continue to do so going forward

3. (Unsaid) You should (continue to) invest in Berkshire Hathaway to enjoy outstanding returns

In addition to this, he does cover a couple of additional aspects – e.g. a fond farewell to Tony Nicely (the retiring CEO of GEICO, Berkshire’s flagship insurance player). But these are add-ons. His Big Story consists of the key messages above.

Of course, a good Big Story isn’t enough; you need the little elements – the toppings – to enhance your story.

II. Adding the Key Story Elements

1. Analogies: Explaining the performance of 75 companies across multiple sectors was going to be tough. Buffett brilliantly simplifies it using the analogy of a forest. Asking analysts to resist the temptation of doing a company-by-company analysis of Berkshire’s value, he likens their holdings to a forest filled with five ‘groves’. Here he goes:

“Investors who evaluate Berkshire sometimes obsess on the details of our many and diverse businesses – our economic “trees,” so to speak. Analysis of that type can be mind-numbing, given that we own a vast array of specimens, ranging from twigs to redwoods. A few of our trees are diseased and unlikely to be around a decade from now. Many others, though, are destined to grow in size and beauty.

Fortunately, it’s not necessary to evaluate each tree individually to make a rough estimate of Berkshire’s intrinsic business value. That’s because our forest contains five “groves” of major importance, each of which can be appraised, with reasonable accuracy, in its entirety. Four of those groves are differentiated clusters of businesses and financial assets that are easy to understand. The fifth – our huge and diverse insurance operation – delivers great value to Berkshire in a less obvious manner, one I will explain later in this letter.”

Analogies are powerful when they are:

- Simple: Easy to understand and visualise for the reader

- Deep: Have multiple connections with your underlying concept

- Referenced multiple times: In the story, indicating depth and continuity

(For some more examples of the use of analogies – especially a dancing geologist – you can read this earlier post I’d written)

2. Aphorisms: These are concise sayings (told sometimes in the form of a story) that pack in a lot of wisdom. Buffett is a past master at such sayings himself (e.g. “Price is what you pay, value is what you get”).

In this letter, Buffett is critical of companies which don’t show ESOPs (Employee Stock Options) as an expense. Here’s how he uses an aphorism (from another famous dude) to make his point:

“For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on Wall Street.”

Someone described proverbs as “Short on words, long on meaning”. I concur.

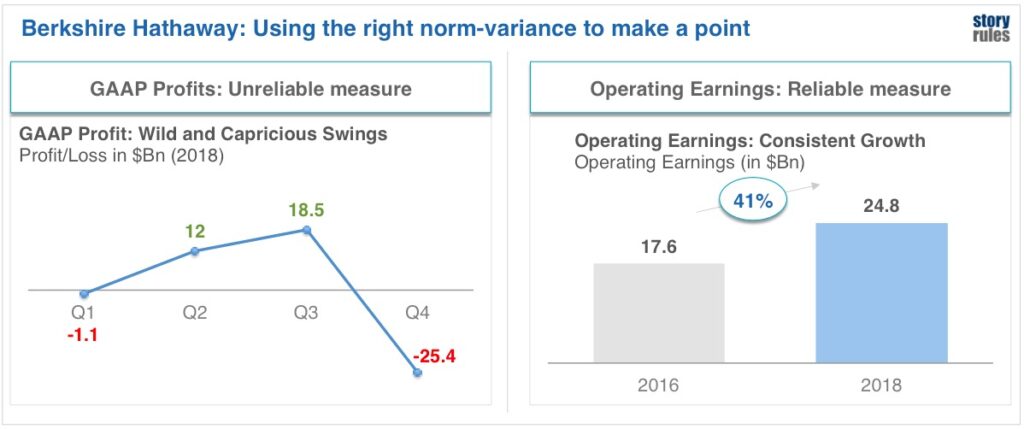

3. Norm and variance: We have written about this powerful storytelling concept before (and how Steve Jobs and Elon Musk used it). Buffett uses it at multiple places – for example in the below instance where he talks about the right (and wrong) performance measures:

“In the first and fourth quarters, we reported GAAP losses of $1.1 billion and $25.4 billion respectively. In the second and third quarters, we reported profits of $12 billion and $18.5 billion. In complete contrast to these gyrations, the many businesses that Berkshire owns delivered consistent and satisfactory operating earnings in all quarters. For the year, those earnings exceeded their 2016 high of $17.6 billion by 41%.”

I’ve tried to represent the above through some simple graphs:

In another example, he extols the virtues of the American economy’s tailwind – that has propelled growth across sectors, through good times and bad.

“If … $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, (the) stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019.… (if you had) opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75… You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business.”

He then finishes with a flourish of wordplay:

“The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.”

4. Pithy, conversational humour: Buffett never misses an opportunity to poke some harmless fun – especially at himself and his business partner, Charlie Munger. Here’s his take on their age:

“We continue, nevertheless, to hope for an elephant-sized acquisition. Even at our ages of 88 and 95 – I’m the young one – that prospect is what causes my heart and Charlie’s to beat faster. (Just writing about the possibility of a huge purchase has caused my pulse rate to soar.)”

“In addition, certain shareholders will simply decide it’s time for them or their families to become net consumers rather than continuing to build capital. Charlie and I have no current interest in joining that group. Perhaps we will become big spenders in our old age.”

And that’s not all – there are more. For example, when explaining the reasons for why the ‘Share book value’ metric isn’t relevant anymore, he uses another storytelling concept: ‘The Rule of Three’ – and gives three reasons for why it doesn’t work.

(I thought of including it as a story element, but it was, well, violating the same rule, so I decided to keep it as an ‘extra’ item!).

Another striking aspect is the use of everyday conversational English, and not drowning the audience in business and financial jargon.

What could be better?

Superlative as the letter is, it could still be better in … three ways (there you go):

- Spell out the Big Story more clearly: As of now, I am inferring some of the bigger messages. It would be nice for Buffett to clarify those himself

- Reduce the preponderance of accounting terms: These may be a put-off for the non-financially savvy reader. I could get most of what he was saying (I’m a CA, guilty as charged), but someone who doesn’t understand financial analysis may struggle in some sections.

- Some visuals: The letter is worded evocatively – but perhaps some visuals/charts would make comprehension easier (such as the norm-variance one).

Unenviable task, Enviable result

Buffett may have a tough storytelling ask, but he sure proves his ‘magical mettle’ at it. I’ll be looking forward to many more such letters from him.

*****

Featured image credit: From Wikimedia Commons by USA International Trade Administration