Where did ‘Indians’ come from?

We open with a book called ‘Early Indians’ and then there are recommendations for several articles (I did say it was a bumper issue!).

📘 Book/s of the week

a. ‘Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From’ by Tony Joseph

On 24th September 1924, John Marshall, the then head of the Archeological Survey of India announced this in the Illustrated London News:

“Not often has it been given to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenae, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long forgotten civilisation. It looks, however, at this moment, as if we were on the threshold of such a discovery in the plains of the Indus.”

This discovery was a seismic event in the study of human history. A long-forgotten civilisation had been unearthed on the banks of the mighty Indus river (and later also the Ghaggar-Hakra river system). The Indian subcontinent’s history had just been pushed back by a few thousand years.

Over the next several decades, as the many wondrous finds that tumbled out from sites like Harappa, Mohenjo Daro, Dholavira and Rakhigarhi wowed us with their findings, they also gave rise to innumerable unanswered questions: Who were these people? What language/s did they speak? How come they didn’t create massive structures for their leaders and Gods like the Egyptians or Mesopotamians? How come they did not have too many warlike depictions on their seals etc., in contrast with other civilisations? How were they able to impose their incredible order and standardisation in urban planning across cities that were thousands of kilometres apart?

What led to their decline? Why were the cities abandoned en masse? What happened to these people? Their language, their customs?

Also, did they interact with the band of Sanskrit-speaking horse-rearers called the Arya, who were said to have migrated to India sometime in 2000 BCE? What came of their interactions? Why did the Vedic Aryans not adopt the stunning city-building practices of the Harappans?

Also, which river was the mythical Sarasvati which is venerated so richly in the Vedas? Is it the current day Ghaggar-Hakra river system along which several Harappan sites have been found or a little-known river in Afghanistan earlier known as ‘Haraxvaiti’? In any case, what led to the Ghaggar-Hakra river system drying up?

So. Many. Questions.

This book answers (almost) all of them.

Well not to 100% certainty, because a lot of these questions are still being investigated. (I would kill for the discovery of a ‘Rosetta-stone‘ equivalent for the Indus-Sarasvati Valley Civilisation).

But this book makes full use of a set of key discoveries from a relatively new science which has revolutionised the study of our ancestry: Genetics.

As Tony writes (emphasis mine):

…our understanding of deep history has changed dramatically in the last one decade or so. Large stretches of our prehistory are being rewritten as we speak, based on analysis of DNA extracted from individuals who lived thousands or tens of thousands of years ago.

Just to get a sense of the speed at which things have moved, consider this: when work on this book began a decade ago, we did not know who were the people of the Harappan Civilization or where their descendants had gone, but now we do.

Speaking of genetics, Tony is impressive in the science-y parts and does a great job explaining the basics of genetics. (I understand it better now!)

But it is not just genetics. ‘Early Indians’ is an impressive confluence of the latest findings from several disciplines: archeology, linguistics, genetics and of course, written history.

If you would like a half-page summary of the book’s findings, the best you can do is read this quirky pizza analogy that Tony uses to explain our ancestry:

Over the four chapters of this book, we saw how the Indian ‘pizza’ got made, with the base or the foundation being laid about 65,000 years ago, when the Out of Africa migrants reached India. The sauce began to be made when a population related to the early Iranian farmers reached Balochistan sometime after 10,000–8000 bce, mixed with the First Indians, and then together went on to build the Harappan Civilization. When the civilization fell apart, the sauce spread all over the subcontinent. Then came the ‘Arya’ after 2000 bce, and cheese was sprinkled all over the pizza, but a lot more in the north than in the south. Around the same time arrived the major toppings which we see today in different regions in different amounts – the Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman-language speakers. And then, much later, of course, came the Greeks, the Jews, the Huns, the Sakas, the Parsis, the Syrians, the Mughals, the Portuguese, the British, the Siddis – all of whom have left small marks all over the Indian pizza.

So while we take a lot of pride in our Vedic ancestry, this book throws light on the prior migrations that made us who we are.

And if you wonder what happened to the Harappans, well you will find their imprints all around us:

The way houses are built around courtyards; the bullock carts; the importance of bangles and the way they are worn; the manner in which trees are worshipped and the sacredness of the peepul tree in particular; the ubiquitous Indian cooking pot and the kulladh; the cultic significance of the buffalo; designs and motifs in jewellery, pottery and seals; games of dice and an early form of chess (dice and chess-like boards have been found at multiple Harappan sites); the humble lota which is used to wash up even today; and even the practice of applying sindoor and some measurement systems – the ways in which we carry on the traditions of the Harappan Civilization are too many to count.

This Republic Day, if you would like to get to know your own roots better, there’s no better book I can recommend.

📄 Article/s of the week

a. High Variance Management by Sebastian Bensusan

This article by Sebastian uses a very interesting and useful frame – of ‘high-variance vs. low-variance work’ – for thinking about creative work, managing high-quality talent and knowing which aspect/s to optimise for a project.

I loved the way the article begins – with this evocative comparison between dancing for the theater vs. the movies:

On Broadway, actors put on a great show eight times a week consistently. If a dancer actually breaks a leg the play has to stop. So, when Sue, the best dancer in the play, suggests adding a risky-but-awesome jump, the choreographer says no. It doesn’t matter how impressive the jump is if she gets it wrong half of the time. Changes that improve the show but cause mistakes are not worth it. You want high consistency, low variance.

Later, Hollywood decides to make a movie based on the play. Sue is cast and she performs the original choreography perfectly in the first take. But the movie director asks: “What else do you have?”. Sue remembers the risky jump. She tries twice before she lands it, but when she does, it makes the scene that much better.

The movie and the play are working under very different constraints:

– The movie only needs one good take, which will be seen by every viewer.

– The movie can discard any bad takes.

In Hollywood, you should be trying to do the very best in every take (see the appendix), even if that means that you’ll make many mistakes. You want high variance, low consistency.

The rest of the (short) article describes how to recognise high-variance vs. low-variance work, and how to get the best outcome from high-variance work.

b. Treat your to-read pile like a river, not a bucket by Oliver Burkeman

When the Information Revolution hit us and we faced a deluge of information from various sources, we grappled with the challenge of ‘filtering’ – separating the wheat from the chaff.

No longer so, argues Oliver Burkeman (author of the bestselling book on ‘Four Thousand Weeks‘). According to him:

The problem, as the critic Nicholas Carr explained, isn’t filter failure. It’s filter success. In a world of effectively infinite information, the better you get at sifting the wheat from the chaff, the more you end up crushed beneath a never-ending avalanche of wheat.

…

My challenge, information-wise, isn’t about finding a needle in a haystack. It’s that I’m confronted on a daily basis, in Carr’s words, by “haystack-sized piles of needles.”

I have the same feeling, not just for stuff to read or listen to, but also work projects to do – I have so many ideas I would like to work on, and just not enough time!

In other words, ‘Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, ki har khwaish pe dum nikle’.

Sure it is an “archetypal first-world problem” as Oliver admits. Still it needs to be addressed. How? Not by applying prioritisation frameworks ad-nauseam, but instead recognising the limits of our optimisation techniques:

It’s not a question of rearranging your to-do list so as to make space for all your “big rocks”, but of accepting that there are simply too many rocks to fit in the jar. You have to take a stab at deciding what matters most, among your various creative passions/life goals/responsibilities – and then do that, while acknowledging that you’ll inevitably be neglecting many other things that matter too.

To return to information overload: this means treating your “to read” pile like a river (a stream that flows past you, and from which you pluck a few choice items, here and there) instead of a bucket (which demands that you empty it).

In other words, recalibrate your expectation from life and be happy that you have a problem of plenty!

(Hat/Tip: #ROTD by Swanand Kelkar and Saurabh Singh)

c. ‘AI is the end of writing’ by Sean Thomas

The writing about ChatGPT can be broadly divided into two camps. The tech-optimists who say “Sure this is revolutionary, but we have had revolutionary ideas before and this can be used by good writers to become better. Plus you cannot replace the authentic content and voice of a good writer”.

And then there are the pessimists, among whom stands this writer. He says:

It’s at this point that the usual essay on ChatGPT points towards something consoling. Something like ‘Ah, but do not despair, humans will always yada yada’. I’m afraid I am not here to offer any such solace. I’ve done writing of all kinds for several decades, from travel journalism to art journalism to political journalism, from literary fiction to youthful memoirs to notorious-letters-to-No-10 to Fifty Shades porn (a pseudonym) to, lately, religious or domestic thrillers. And I have to say: we are screwed. By which I mean: we, the writers. We’re screwed.

Why does he state this gloomy forecast? Because:

All writing is an algorithm. As in: all writing is ‘a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations’. The fundamental problem to be solved in writing is how to impart information in the form of words.

Computers are good at algorithms. It’s their thing. That means that, given enough data to train on (e.g. all the words ever written on the internet) computers can get really good at running the algos of language. As we can see with ChatGPT. Especially as AI is a dab hand at algorithmic autocomplete: predicting what words should usually follow from words already given.

He then goes on to outline the likely spread of AI to different forms of writing. From “easy” ones like college essays, entry-level journalism, copywriting, marketing content, tech writing to eventually being able to write magisterial novels with complex plots and characters.

What will happen to those who write then? Sean does not have a good prognosis:

A few human brand-names might be used to promote expensive fiction written by the machines. Memoir and travel writing might be OK (aha!) because computers can’t go to war, get addicted or sip excellent mojitos in the Maldives. Perhaps there will be a genre of resistance literature, stuff that’s not as good as the machine stuff but has a radical emotional value, because it is ours, because it has survived. We still buy rough artisanal pottery, and admire wobbly vernacular architecture, because of the deep human emotions embodied.

But this is seriously niche. For the rest of us, the verdict is bad, sad and terminal. 5,000 years of the written human word, and 500 years of people making a life, a career, and even fame out of those same human words, are quite abruptly coming to an end.

For the sake of writers everywhere, hopefully his predictions are too pessimistic to play out.

d. ‘Why Indian players need to be more aware of caste privilege and oppression’ by Sidharth Monga

An eye-opening article by the excellent Sid Monga on the unfortunate tendency by some Indian players/officials to use casteist slurs in a ‘harmless’ way.

During the Covid-19 lockdown, when players started to interview each other on Instagram, Yuvraj Singh, in a chat with Rohit Sharma, referred to Yuzvendra Chahal as a bhangi for his “cringe” TikTok videos, to the sound of laughter from Rohit. Again, bhangis are a community who, by accident of birth, were and are restricted to cleaning drains and toilets.

When the matter blew up, Yuvraj responded with a non-apology, saying he was “misunderstood, which was unwarranted”. He expressed regret “if” he had “unintentionally” hurt someone’s feelings.

We are in 2023. Ignorance can no longer be an excuse.

🎤 Podcast/s of the week

a. Early Indians – Tony Joseph in conversation with Amit Varma

Before I pick up a book by an author, I try to find out if he or she has been interviewed on a podcast about the book. If that interview is by Amit Varma (of the Seen and the Unseen podcast), then jackpot!

If you don’t get the time to read Tony Joseph’s book, this conversation is a great summary. Listening at 2x, you can get the gist in about 45 mins.

🐦 Tweets of the week

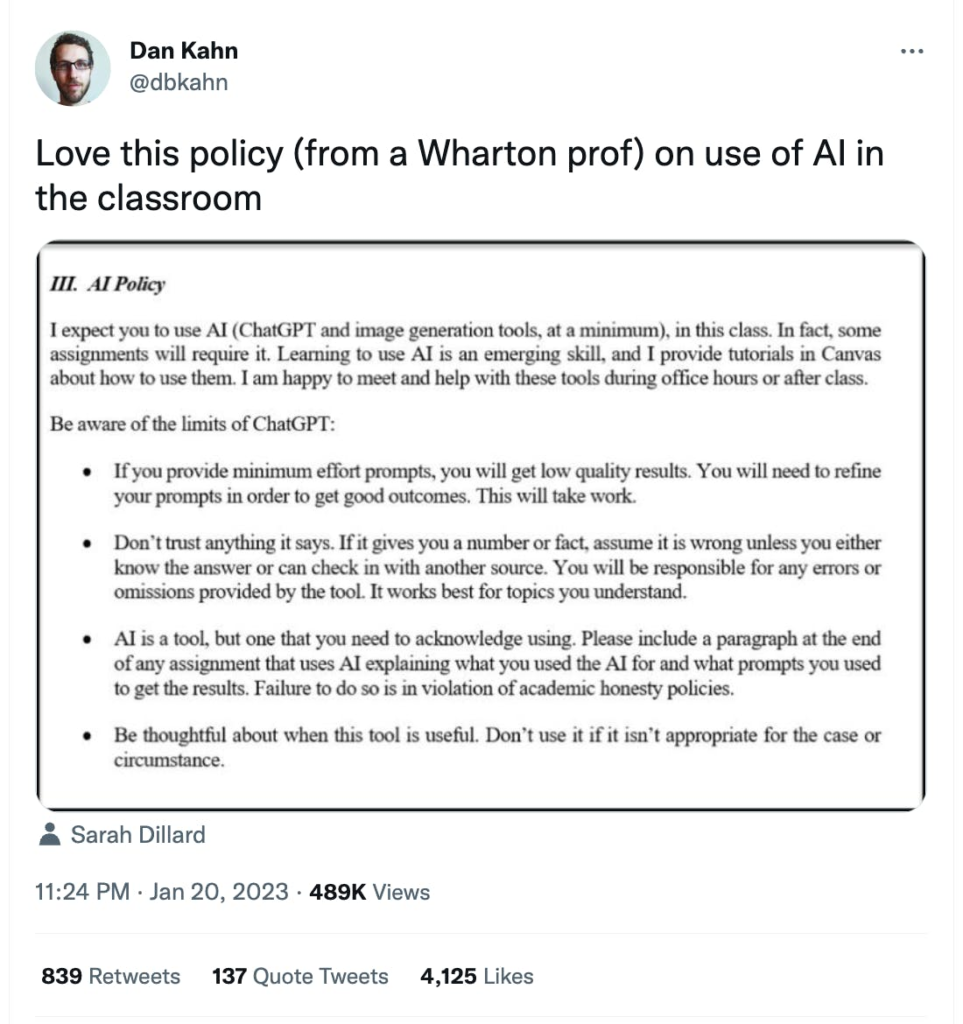

This is a neat approach for professors to work with AI:

As a recent victim of this, I agree! Need to do more yoga…

Seriously Starbucks, no Tamil ‘paati’ can approve this:

💬 Quote of the week

“It is often during periods of climatic upheaval… that we see new dramatic developments taking place in human history, proving once again that our species needs either fear (lack of resources) or greed (promise of plenty) to propel it forward”

– Tony Joseph, in ‘Early Indians’

📺 Video/s of the week

a. The Top 10 Ads of 2022 by Karthik Srinivasan (9:01)

Karthiks (@beastoftraal on Twitter) is a superhuman chronicler of ads from India and the world. In this delightful collection he shares his take on some remarkable ads in 2022. (Here is the link to the post with the actual ads).

Apart from the popular Spotify ads, I especially loved those by Sabhyata and Hyatt.

📢 Announcement of the week

After Story Rules on Saturday #100, I’m going to be taking a break from this long-ish format and instead replace it with a lighter weekly email. I plan to use the freed-up time to focus on more long-form original writing, podcasts and #SOTDs.

But first some context.

It seems just some time back that I started this initiative of sharing my regular reads with an external audience. I looked up my files and realised that I had sent my first newsletter called ‘Fortnightly Food for Thought’, with a collection of summaries of five articles, way back on 20-Oct-2017 (through the firm Mind Matters then).

Since then, the format has undergone several iterations

- From Fortnightly, it became a Monthly effort

- I then moved it from Mind Matters to my own brand, Story Rules

- Later, I started it as a weekly email called ‘Story Rules on Saturday’, which was initially a mixed bag (some content recommendations, some blog posts by me, some podcast episodes)

- Eventually it moved to the current format of a list of content recommendations under several heads (Books, articles, podcast episodes, tweets, quote, videos/movies) and the occasional podcast episode

And now, as I stand on the milestone of a 100 ‘Story Rules on Saturday’ emails, I’m stepping back and rejigging the format again.

What will the new, lighter one look like? How exactly will I use the freed up time? What’s in it for you? All to be answered in the next week’s edition. But for now, it’s a sign-off from this detailed and effort-intensive content recommendations long-list.

See you next week with the new format.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the week.

Photo by Manyu Varma on Unsplash