7 tips to get your story narrative in shape

A post on narrative

An effective data-story has three parts: Narrative, Visuals and Delivery. This is a (long and geeky) post on narrative.

I was browsing my Twitter feed recently, when I came across a Vox article with an intriguing title: “Why you shouldn’t exercise to lose weight, explained with 60+ studies”.

WHAT? An article that’s telling me I shouldn’t exercise?! That too based on scientific evidence? I gotta read this, I thought.

And the contents were worth it – I found some findings quite stunning, and essential reading for anyone interested in managing their health and weight (which is, basically every adult).

In a nutshell, here’s what the article says: “Want to reduce weight? Exercise has a marginal to negative impact (though it has other significant benefits). Focus on diet instead.”

While the premise is super-interesting, I found the storyline could do with a lot of improvement. And so, I’m going to analyse the issues and rework the narrative.

If you’ve got the time, and really want to do this right, you should quickly glance through the original article before reading ahead. Else, go on ahead – you’ll get the basic idea anyway.

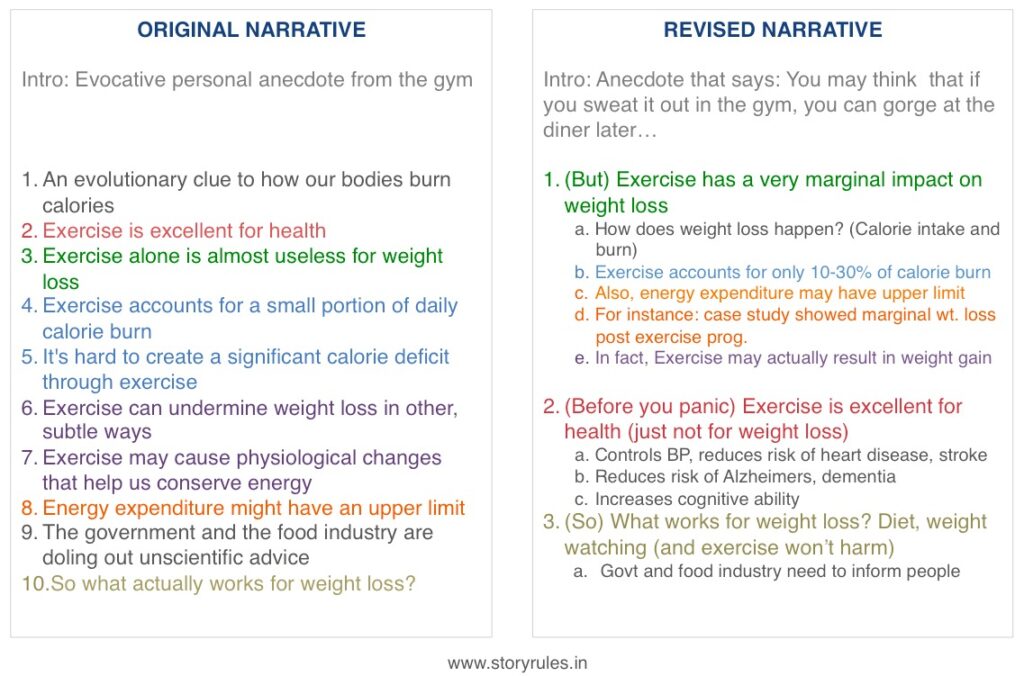

The original narrative

The article starts with an evocative anecdote from the gym and is then structured around 10 key points:

1) An evolutionary clue to how our bodies burn calories

2) Exercise is excellent for health

3) Exercise alone is almost useless for weight loss

4) Exercise accounts for a small portion of daily calorie burn

5) It’s hard to create a significant calorie deficit through exercise

6) Exercise can undermine weight loss in other, subtle ways

7) Exercise may cause physiological changes that help us conserve energy

8) Energy expenditure might have an upper limit

9) The government and the food industry are doling out unscientific advice

10) So what actually works for weight loss?

On a first reading the narrative seemed pretty ok to me – I was more focused on the findings themselves. But on a second reading I realised that it’s got many flaws. Let’s uncover some of them.

Analysing the existing narrative: what works well

The following aspects are actually quite good:

i. The Right ‘Point A’: The article starts well – with an evocative situation from the gym that’s basically saying “we all believe that if we exercise enough, we can eat what we want”. The reason the start is so effective is that most readers would be able to relate to the gym situation (or at least the belief on exercise exonerating you from diet control).

Why is that important? So, when you’re writing an article or a presentation, think of it as moving the audience from their current position on a topic (say, Point A) to a new position that you want them to believe (say Point B). So your start should be from (duh) Point A: a place that the audience already believes or can relate to.

To illustrate with another example, if you’re starting a quarterly sales review presentation, a good Point A would be the target for the quarter, or the last year’s quarterly sales number.

ii. A clear ‘Point B’: Continuing from the above point, any communication should end with the final takeaway and call to action. Net-net, what do you want to leave the audience with? This article (after debunking the claim that exercise helps in weight reduction), ends with the key question – so what does?

iii. Assertive statements: Each section of the article (except for the first one) is headed by a clear, assertive statement (think of it as a slide heading), instead of a dry title (for e.g. ‘Exercise is excellent for health’ is much better than ‘Effect of exercise on health’). Drop the suspense, give out the answer in the message.

To sum up: the beginning, the end and the statement titles of the article are pretty good. But there’s plenty I thought could be better.

Analysing the existing narrative: what could be better

i. Narrative dump: To me the statements between Point A and Point B, seemed like a ‘narrative dump’ – a long-list of the findings from the studies without a clear attempt to structure them, and build into a coherent storyline.

ii. Weak connectives: A good test of a storyline is this – is there a strong link between two messages? Every time you move from one message to another (say from P to Q), if you don’t give them the logic for why Q is following P, you are risking losing your audience’s attention.

So, what can help in building the logic? Connective words. These are the silent back-stage workers of the English language – words like ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘therefore’, ‘despite’, ‘notwithstanding’ – which ensure that the transition from one scene to the next is smooth.

Here’s an example of 4 messages without connectives:

- Jack went up the hill.

- Jill went up the hill.

- Jack and Jill are not friends.

- Jack fell down and broke his crown.

Here’s a ‘connected’ version of the above:

- Jack went up the hill,

- And Jill went up the hill.

- But Jack and Jill are not friends.

- Then Jack fell down and broke his crown.

Hm, that’s jarring. Let’s try again (with a small addition in the plot, using storyteller’s license):

- Although Jack and Jill are not friends,

- When Jack went up the hill,

- Jill also went up the hill.

- (Then we don’t know what happened,)

- But Jack fell down and broke his crown.

- (I’m not pointing the finger at you Jill, but you were the only other person there, that’s all I’m saying)

Anyway coming back to the Vox article, there are no connectives between the statements. You may say that there is a link: the word ‘and’.

So here’s the thing: A connective can be weak or strong. Words like ‘and’, ‘then’, ‘further’, which are ‘additive’ in nature are weak connectives. Connectives that emphasise contrast (‘but’, ‘despite’, ‘nevertheless’) or cause-and-effect (‘because’, ‘therefore’) are far more stronger, because they imply conflict or movement in the story. And they’re far more effective at holding the reader’s attention.

In the Vox article storyline, there are no strong connectives used… (wait for it), despite such connections being present between the messages. We will explore those when we redo the narrative

iii. Levels: Messages have ‘levels’. Some are at a higher level, while some are at a subordinate level. Here’s an example of a set of messages without levels:

- Jack and Jill go back a long way

- They like to do their chores together

- They also have a history of attempting life-threatening short-cuts down steep surfaces

- But they aren’t friends anymore

- It all started at Little Miss Muffet’s party

- Jack was rude when Jill asked for an extra serving of whey

- And now their friends are distraught about having to take sides

- Little Bo Peep doesn’t want to pick among friends; first she lost her sheep, and now this

- At least Mary has her little lamb, but wants Jack and Jill to patch up.

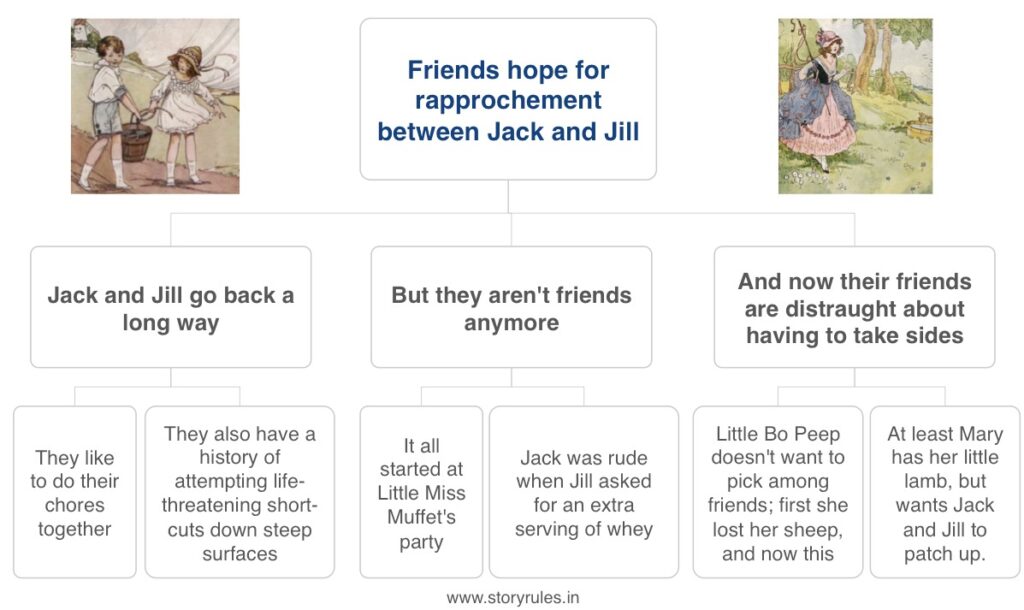

Again, jarring right? Let’s attempt it with 2 levels:

- Jack and Jill go back a long way

– They like to do their chores together

– They also have a history of attempting life-threatening short-cuts down steep surfaces

2. But they aren’t friends anymore

– It all started at Little Miss Muffet’s party

– Jack was rude when Jill asked for an extra serving of whey

3. And now their friends are distraught about having to take sides

– Li’l Bo Peep doesn’t want to pick among friends; first she lost her sheep, and now this

– At least Mary has her little lamb, but wants Jack and Jill to patch up.

Much easier to read? You can quickly read the three main messages; and then go through the supporting sub-messages. In fact, with such a structure, we can (and must) go a level further up. Can we summarise the three main messages in one line? Perhaps “Friends hope for rapprochement between Jack and Jill”

Visually, can you see a structure emerging here? Let’s attempt to put it on a slide:

Some of you may have recognised that the structure above is derived from the Pyramid Principle, a concept pioneered by Barbara Minto an ex-Mckinsey consultant. It consists of finding out the one main answer/message and then supporting that with key sub-messages, which are in turn supported by further messages… Many consultants swear by this format for all kinds of business communication – presentations, emails, reports et al. The Pyramid-Principle clearly does have a lot of merit, and should definitely be one of the tools in the storyteller’s arsenal.

Coming back to the original Vox article, having 10 messages at the same level makes it very difficult for the reader to comprehend it. At the top level, a story should have at most 4-5 messages. All other messages should be subsumed within one of the top messages. With the above pointers in mind, let’s redo the Vox article narrative.

Redoing the narrative: process

Working out a coherent narrative is probably the most difficult skill in storytelling. What should be the key top-level messages? At what level and position in the storyline does a particular message fit? What should be the flow? What connectors make sense at a particular juncture?

I frequently get stuck at this stage and find it very challenging to keep my focus. One technique that helps is to write the messages down (pen and paper, not on the computer) and study them. Or better, put down the messages on chits/post-it notes, and spread them on a table – makes it easier to ‘move around’ the messages.

You could use the following sequence of steps:

- Club the related messages together, and figure out if one of them is at a higher/lower level than another

- See which messages can be linked/connected with others

- Check if you need to add over-arching messages to encompass a set of statements at a ‘lower level’

- If some finding is redundant, don’t hesitate in ignoring it in the main narrative

- Play around with the chits till you arrive at the sequence that seems appropriate

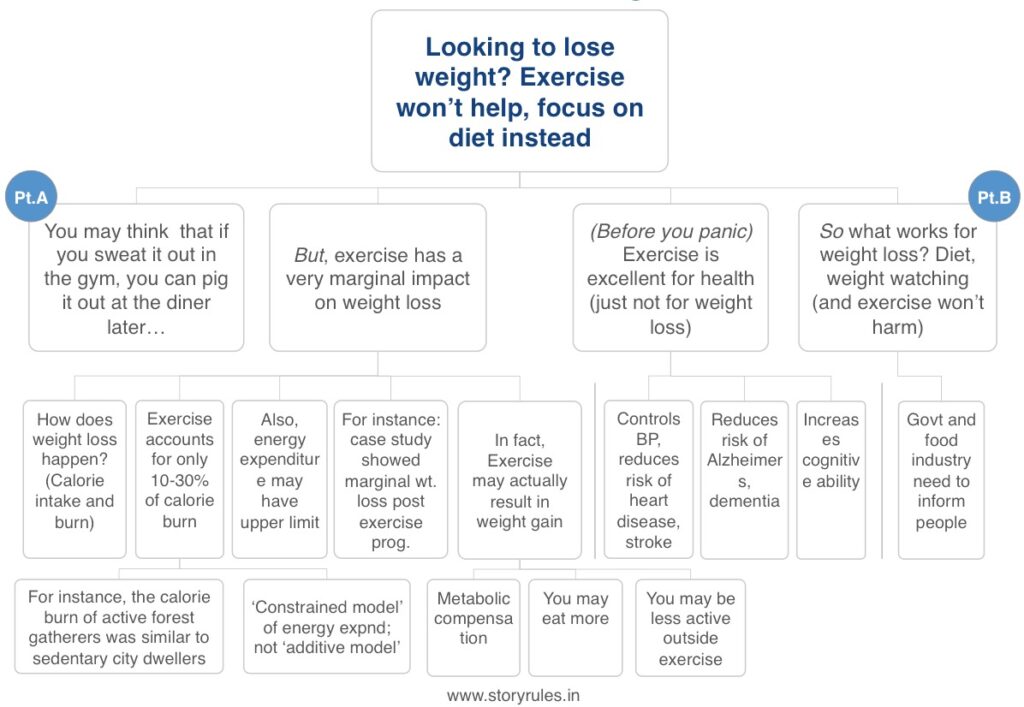

The revised narrative

So here goes – the revised narrative. Not exactly pyramid-shaped, but uses some of its principles.

If you compare the revised storyline with the original:

- Some messages have been moved to lower levels (e.g. #1, 4, 5, 8…)

- Some have been rearranged (e.g. #3: Exercise being good, has been pushed to later)

- Some have been combined into a common one (e.g. #6 and 7 from the original)

Summarising: The Seven Tips

So here are the 7 tips for building a coherent narrative for your next presentation/report:

- Have a clear Point B (always better to begin with the end in mind)

- Start from the Right Point A

- Messages to be assertive statements (not descriptive titles)

- Structure the messages into levels – use the Pyramid Principle

- Keep summarising messages across levels – and at an overarching level

- Look for and build (strong) connections between messages

- For sequencing the messages, write them down on chits/post-its and ‘play around’ with the order

And a bonus 8th tip: If something doesn’t fit in with the narrative, keep it in the appendix/backup section. Just because you’ve found something interesting, it doesn’t have to be showcased in the main narrative.

Do you have more tips to add to the list? Please share in the comments.

*****

If you found this story useful, please subscribe for email updates of new blog posts from Story Rules.

Featured image: Photo by Local Fitness, Australia [Attribution, CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons