Causality: The Elusive C at the Heart of Story

October 14, 2023 2024-01-30 9:42Causality: The Elusive C at the Heart of Story

Author’s note: This essay was originally published on 14th Oct 2023. You are reading a slightly revised version of the essay.

“Numbers batao, Kahaani mat sunao”

“Tell me the numbers/truth. Don’t make up stories” – is a common statement heard across many boardrooms and boss’ cabins. Unfortunately, it implies that stories = fiction.

But stories can be told from facts too. If told well, stories based on facts (or data) can help the audience find clarity in a confusing mass of information. If told well, they can engage the audience’s fickle and falling attention. And if told well, a good data story can persuade the recipient to make the right decision.

If told well.

So what stops a story from being effective? The lack of data? A rambling narrative? Text-heavy slides? Insipid delivery?

All these factors matter. But there is one foundational element at the core of every story that most people disregard. Think of this element as the API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) of the story. Without it, the story ‘tablet’ is just a combination of some artificial colours, flavours, and binding agents.

In this long-form piece, I’ve delved into the fundamental nature of stories as a form of sharing information. And I’ve tried to answer foundational questions about this critical craft: What is a story really? Why does it matter? And what is that core ingredient within a story that ensures its robustness? And most importantly, how can you create stories that are as effective – as close to the truth – as possible?

Stories that are so clear, compelling, and accurate that, the next time your senior would tell you: “Sirf numbers nahi. Numbers ki kahaani sunao.” (“Don’t just tell me the numbers. Tell me their story.”)

In mid-2017, I was facilitating a data-storytelling workshop for a leading airline services company. In the session, I met Ankit1, a boyish-looking business unit leader at the company.

Ankit was excited to present his division’s quarterly performance since they had delivered a whopping 4X annual revenue growth. He was also sure of the reason driving the spike – the new ‘dynamic pricing policy’ his division had implemented. He should know; after all, he was instrumental in implementing it.

The new pricing policy was innovative for sure, but Ankit’s contention that it was the main driver of the sales increase was wrong. Like many others, Ankit had fallen victim to the flawed causality trap.

What is a story really? Is it a series of incidents that happened to certain people? Does it need to have a beginning, middle and (duh) end? Does it need to have a moral?

And how important is it in our lives? Is it merely a tool for entertainment? For putting kids to bed? For Netflix binge marathons?

Or is it something that is more core, that is fundamental to our being? Something that governs all aspects of our lives. Something we use in almost every action, every decision, every thought we have.

And if stories turn out to be so critical, should we not understand them better?

Especially the core ingredient at their heart?

Let’s begin.

Contents

1. CAUSALITY IS AT THE HEART OF STORY AND ALL OUR ACTIONS

It all starts with desire.

Who are we? At the most fundamental level, we are carriers of our ‘Selfish Genes’, as Richard Dawkins writes2:

We are survival machines – robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes.

Our genes desire replication and use our bodies as temporary vessels to carry them till they find the next carrier. But the vehicles in this case are not dumb machines – they are incredibly complex living beings with their own physiology, thoughts, skills, fallacies, and yes, desires.

Survival and propagation of our species might be the ultimate desire. But stacked on top of this fundamental need are a dizzying and never-ending array of needs, wants, and dreams.

How does one even begin to understand this core and fundamental phenomenon of desire that makes the world go round? We could fill libraries with books written on desires, but for the purpose of this essay, let’s understand five of their core characteristics.

i. Desires have hierarchy

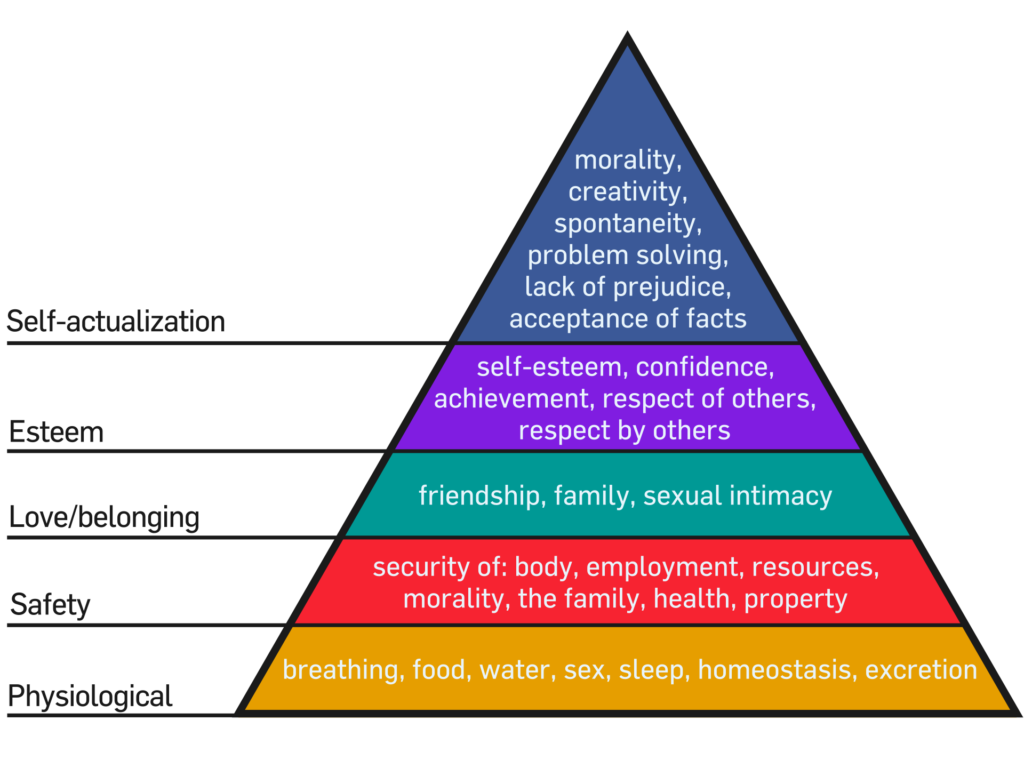

To understand this, we turn to the work of the oldest son of Jewish immigrants from Kiev, Ukraine who were fleeing from Russian persecution in 2022 the early 20th century.

Abraham Harold Maslow grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and was often found in libraries and among books. He studied psychology at the University of Wisconsin and went on to contribute several ideas to the field, including: humanistic psychology, peak and plateau experiences, and self-actualization. But his seminal contribution was through a 1943 paper called ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’ in which he laid out the famous ‘Hierarchy of Needs3’

Human needs arrange themselves in hierarchies of pre-potency. That is to say, the appearance of one need usually rests on the prior satisfaction of another, more pre-potent need. Man is a perpetually wanting animal. Also, no need or drive can be treated as if it were isolated or discrete; every drive is related to the state of satisfaction or dissatisfaction of other drives.

Maslow’s theory has its critics, but it remains the simplest, yet most profound classification of our desires.

For most of history, the vast majority of people were grappling with meeting just the basic needs at Levels 1 and 2 of the hierarchy. But over the last few centuries, driven by advancements in science and technology, hundreds of millions of people have escaped the poverty trap and are mainly focused on meeting their needs at Level 3 (Belonging) and Level 4 (Esteem/Status).

We all feel the need to belong to various communities. Apart from family, friends, and the workplace, we ‘belong’ to various groups: our apartment complex, sports teams, quiz leagues, pet-lovers groups, music clubs, runners’ bands, poetry gatherings, trekking communities, and so on. Then, there’s a whole different world of online communities – whether through social media platforms like WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Reddit, or through other pursuits like stock investing, sports fandom, online gaming, or the metaverse.

In each of these communities, we don’t just crave belonging (Level 3) but we also desire status (Level 4) and will go to great lengths to increase our reputation within these groups. Journalist and writer Will Storr calls it the ‘Status Game4’ in his book by the same name.

We’re obviously driven by a great many impulses – and usually several at once. An inventor may be motivated by insatiable curiosity and the joy of problem-solving and desire to pay their mortgage, for example, as well as by the urge to impress their peers. Status is what researchers call an ‘ultimate’ rather than a ‘proximate’ drive: it’s a kind of mother-motivation, a deep evolutionary cause of many other downstream beliefs and behaviours that’s been favoured by selection and is written into the design of our brains.

ii. Desires are mimetic

Where do desires originate? According to philosopher Rene Girard, most of it comes from imitation, as Luke Burgis writes in ‘Wanting5’:

Girard discovered that most of what we desire is mimetic (mi-met-ik) or imitative, not intrinsic. Humans learn—through imitation—to want the same things other people want, just as they learn how to speak the same language and play by the same cultural rules. Imitation plays a far more pervasive role in our society than anyone had ever openly acknowledged.

You might, of course, see the connection between our need for belonging and the mimetic nature of our desires.

iii. Desires are never-ending

The more we have the more we want. This intuitive truth has been proven through empirical evidence, as reflected in these two studies, referenced by Will Storr in ‘The Status Game6’:

A team led by psychologist Professor Michael Norton contacted over two thousand people whose net worth started at one million dollars and rose to an awful lot more. They were asked to rate their happiness on a ten-point scale, then say how much cash they’d need to be perfectly happy. ‘All the way up the income-wealth spectrum,’ Norton reported, ‘basically everyone says two or three times as much.’

Take this funny clip where Louis CK talks about how quickly our desires “move up” when the existing ones are fulfilled.

I was on an airplane and there was high-speed internet on the airplane. That’s the newest thing that I know exists. And I’m sitting on the plane and they go “Open up your laptop you can go on the internet” and it’s fast and I’m watching YouTube clips … and then it breaks down and they apologize. The Internet’s not working the guy next to me goes “Pfft” (in disappointment). Like how quickly the world owes him something (that) he knew existed only 10 seconds ago

In fact, this aspect of desire is one reason why automation and AI might never kill all jobs. When we think jobs will be automated, we are thinking of current jobs. But current jobs are tied to current desires. And because we will find new desires, we will find new jobs to fulfill them. Jobs have continually evolved – from traveling couriers to telephone operators, from painters to photographers to Photoshop designers, from farm hands to factory workers, from itinerant entertainers to Instagram influencers, from programmers to prompt engineers, from accountants to, well accountants (accountants will never die, buwahahaha) – and new desires will keep evolving, creating new jobs for humans and AI alike.

iv. Desires need to be prioritised/optimised for

We can never have everything. If we desire to remain fit, we may need to eat less. A house with a great view might be near a noisy street. A career that gives us financial stability might not necessarily give us joy and personal fulfillment. The website platform that’s great for blogging might not have the best user interface. We need to be clear about what desire/s we are optimizing for.

In relation to this idea, Burgis (in the book ‘Wanting’) gives a useful frame of ‘thick vs. thin desires’. Often we have a lot of desires that are thin – for instance, I have been wanting to learn Hindustani Classical music for years now. But if it was a thick desire, I would have already started! Reading non-fiction is a thick desire for me – I manage to find time for it even on vacations.

v. Freedom from desire is at the core of our ancient philosophy

The Bhagwad Gita says: Don’t get attached to desire, focus on your Karma or Action. Buddhist philosophy is all about ridding oneself of all attachments or desires. Clearly, the ancients were onto something in understanding the centrality of desires on our happiness and mental well-being.

But let’s face it – we are ordinary mortals stuck in the messy real world of trying to optimize and meet our unlimited desires. Desires that don’t fulfill themselves. Desires that compel us to think, discuss, decide, and most importantly, do something.

That brings us to A: Action

We are driven by desire and we need to act to fulfill them. We breathe, eat, drink, sleep, work, meet people, connect with them, fall in love, marry, procreate, raise kids… all so that we can fulfill our varied desires.

If desires are the carrots that entice us toward them, actions are the physical and mental effort we expend to undertake the journey.

But when we act, how do we actually fulfill our desires? Not just humans but all living things: animals and birds and insects and microbes and plants – what resource do we use to meet our wants?

It’s time to introduce the next ingredient into the mix: The Environment

In this essay, the ‘Environment’ refers to:

- All of Earth’s (and the Universe’s) resources – living and non-living

- All other humans

- All of your own resources: your physical and mental abilities and skills, your willpower, and your effort

Over millennia humans have gotten more and more adept at using the Environment to fulfil our desires.

However, there is a fundamental flaw here. Our desires are infinite, but the resources of the Environment are finite.

This is what prompted economist Lionel Robbins (from the London School of Economics) to come up with a succinct definition of the science in 19357:

Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends (Desires) and scarce means (Environment) which have alternative uses.

Alright, so we have gotten three of the main elements that are a part of all stories: Desires, Actions, and the Environment.

There is a missing fourth ingredient – let’s call it ‘C’.

What does C do?

- C is at the heart of the story we tell ourselves and the world

- C is the thread that connects our actions with our desires and the environment

- C is our model for how the world works

C is Causality.

Causality is the thread that connects actions with desires – and stories (a.k.a. narratives) are the receptacles that hold these threads in place.

And in case you are thinking, “Cool, this sounds like something that business leaders would be using for key strategic decisions”, you are mistaken.

ALL of us use causal stories ALL the time

Let’s say you like to go for a morning walk in your neighbourhood. Let’s imagine the inner monologue in your mind during this walk:

As you cross the street, you decide to wait for a bus to pass. Then you notice a centre advertising a popular e-course for Machine Learning and are tempted to explore the potential benefits for your career. You turn into a side street and come across an apartment complex that proudly displays “Rainwater harvesting system installed”. You worry about your building society where the committee members are unable to agree on the same. From across the street, you take in the aroma of freshly baked bread from a local bakery and you think it’ll be nice to have a sandwich for breakfast today. A guy is reading the newspaper and your eyes glance at an article about the upcoming cricket test series between India and Australia. ‘Man, I hope they take Rahane for the first game’, you muse. Winning in high-pressure situations reminds you about the presentation you are making to the CTO at work next week about the expensive but critical software subscription that would significantly enhance the team’s productivity. The software reminds you of the young start-up founder who dropped out of college to launch his SaaS company, sold it at a multi-million dollar valuation, and then went on a year-long sabbatical to see the world. Finally, your thoughts return to a favourite topic – your much-awaited Thailand vacation once the kids’ Diwali vacation begins.

In this brief monologue, every thought was a story – a story with a desire (D), an action (A), and a causal link (C)8 between them:

- If I wait now (A), I’ll avoid getting hit by that bus (D)

- If I enroll in the e-course for Machine Learning (A), I will increase my employability and might get a raise or a better job option in the future (D)

- If our housing society invests in rainwater harvesting (A) we will have less dependence on tankers next summer (D)

- If I have a sandwich for breakfast (A), I will satiate my hunger and have a lip-smacking meal (D)

- If the cricket captain chooses Rahane in his team (A), we will have a better chance of scoring faster and winning the upcoming test series against Australia (D)

- If we get a subscription to software S (A), our team will be more productive (D)

- To make a multi-million dollar exit (D), one doesn’t probably need to finish college (A)

- If we go on a family holiday to Thailand (A), it would be a memorable vacation within our budget (D)

Notice some common elements:

- All sentences have an ‘If-Then’ structure (or can be written as one)

- We don’t explicitly state the A-C-D relationship – but it is there at the subconscious level

- Not all actions are by you – some are by others (cricket captains) and many are joint decisions (like the society).

And ALL stories have these causal connections.

Take fables:

| Fable | Action | Desire |

| The Hare and the Tortoise | If you are slow and steady in your approach | You will win the race |

| The Thirsty Crow | If you are inventive and persistent | You will get your desired reward |

| The Foolish Lion and the Clever Rabbit | If you are vain and greedy | You will be defeated9 |

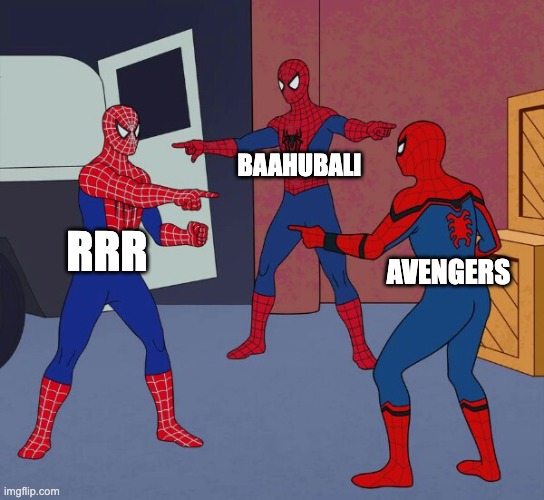

Or Movies:

| Movie name | Action | Desire |

| RRR | If you are determined, inventive, hard-working, strong, etc. | You will defeat even the most powerful enemy |

| Dangal | If you are determined, loyal, inventive, brave, hard-working, strong, etc. | You will defeat even the most powerful opponent |

| Bahubali | If you are determined, loyal, inventive, brave, hard-working, strong, etc. | You will defeat even the most powerful enemy |

| Avengers Endgame | If you are determined, loyal, inventive, brave, hard-working, strong etc. | You will defeat even the most powerful enemy |

(Wait, so they were all different movies?)

But hang on. Where’s the ‘C’ in these statements?

In all these stories the C is the ‘show-don’t-tell’ causal link between the A-D connections.

When you see Ram and Bheem (in the movie ‘RRR’) coordinating to fight back a whole army, when you see Geeta Phogat (in the movie ‘Dangal’) dig into her deepest reserves of will to fight back a tough opponent, when you see The Hulk (in the ‘Avengers’ series) take on an army of evil soldiers, you are seeing the causal relationships in action.

This is not restricted to fiction stories. Let’s take examples of real-life presentations and statements by leaders. I’m considering four real-life examples for the analysis:

- Coinbase: The letter to potential shareholders by CEO Brian Armstrong during their IPO on why they should invest in Coinbase

- Amazon: The response written by CEO, Jeff Bezos, to the US Antitrust Sub-committee on why Amazon should not be broken up

- Sequoia: A deck prepared for their investee companies on the need to cope with the funding slowdown

- Ankit’s company: The quarterly business review presentation for Ankit’s division

Let’s find the Desire-Action-Cause connection for each of these stories:

| Company | Desire | Action | Causal underpinning |

| Coinbase Pitch (link) | If you (investor) wish to benefit financially from the rise of crypto | You should invest in Coinbase stock | The crypto-economy is growing and is the future. Coinbase is best placed to win because of its safe, trusted, and easy-to-use platform. |

| Amazon Statement to the US Antitrust Sub-committee (link) | If you (the government) want the stakeholder benefits to continue | You should not break up Amazon | By focusing on customers and taking big risks, Amazon has enabled extraordinary outcomes for all stakeholders: Employees, Small business and share-owners. Our large size enables massive impact for society as a whole. |

| Sequoia deck to startups (link PDF) | If you (startup) wish to survive (and thrive) in this challenging environment | You will need to prepare your mind, your team, and your company to cope | With the end of the low-interest rate environment, the era of cheap capital has ended. You will need to prepare your mind, your team, and your company to cope. |

| Ankit’s company’s quarterly business review | If you wish to increase revenue | Review your pricing strategy and make it ‘dynamic’ | The recent spike in sales was driven by a better ‘dynamic pricing’ strategy. |

This tells us two things:

- Every story has a causal link (between Action and Desire)

- In most stories, however, the causal relationship is rarely explicitly stated. It is usually implied by the communicator.

This brings us to an important point.

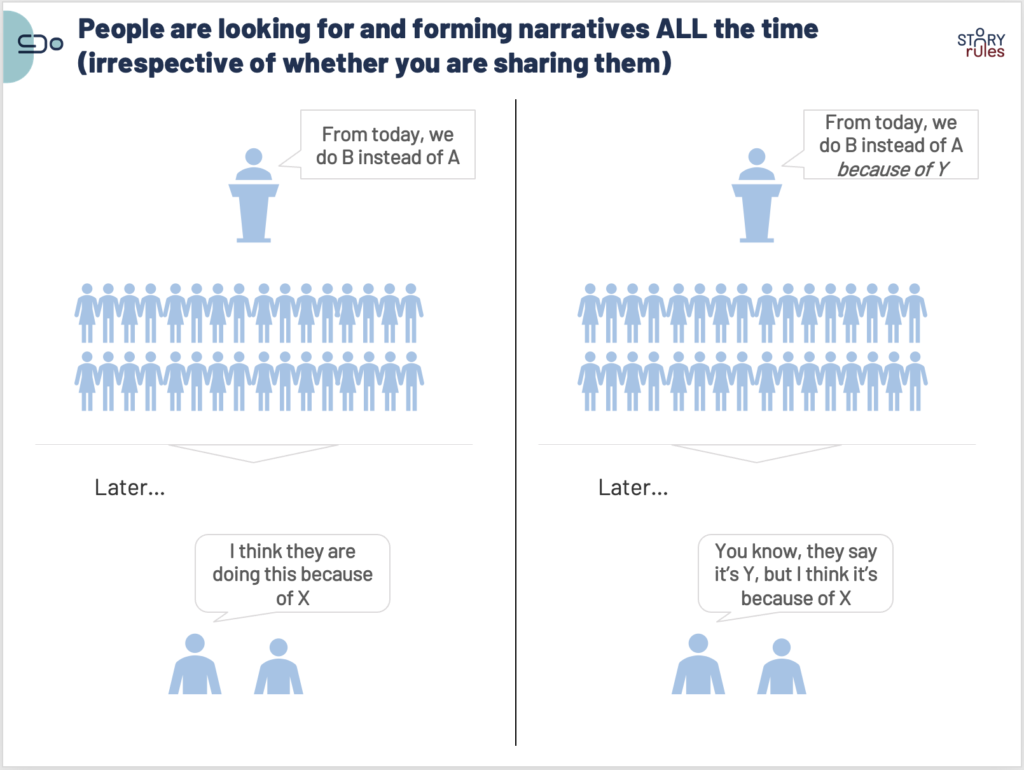

No explicit causal statement does not mean no causal statement (in the audience’s mind).

To paraphrase: If your story does not have a causal statement (or has a very weak one), your audience will assume one themselves.

For instance, say a company announces: “From next month, we will stop providing cabs for employees”. Would the employees take that announcement at face value? Of course not.

Or what if they state a reason that seems implausible? Say: “We are stopping cab pick-up and drop, given our commitment to ESG principles”. Will the listeners accept the stated reason? Most likely, no. That’s because of one crucial property of causality.

Causality abhors a vacuum.

If the communicator does not provide a valid and acceptable reason for the proposed idea or action (and often, even if they do that), the audience will fill in the space with their interpretation of what the reason could be.

Are office cabs being stopped? They must be facing budget constraints. The new product must not be doing as well as they claim.

Famous musician’s performance cancelled? He’s probably onto drugs. And not the medical kind.

The CFO missed the town hall today? I think she was mighty upset during the last meeting and is considering her options outside.

As storytellers, we cannot ignore causality.

There are two implications here:

- Acknowledge that we (and our audiences) make causal inferences in all our statements. So we need to articulate the causal relationship (which might be in an amorphous form in our minds) on paper and share it with our audience.

- We inherently believe in the strength of the causal connections we make. But as we discuss later in the essay, these links are more tenuous than we think. So we need to test the strength of our causal statements using several techniques. Let’s start with an ancient one.

2: AN ANCIENT FRAMEWORK FOR SOLVING THE CAUSAL PUZZLE

If you find yourself thinking “I don’t make flawed causal connections”, may I interest you with a quick quiz?

Have you ever done any or all of the following:

- Visited your favourite place of worship before your exam results announcement (I used to religiously visit the ‘Siddhi Vinayak’ temple in Mumbai for all my CA exams – still believe that’s what got me through).

- Kept sitting in an uncomfortable position because it was ‘making your team play well’. (My carefully calibrated seating position was responsible for India’s cricket World Cup win in 2011, Argentina’s football World Cup win in 2022, and several others in between)

- Your spouse tells you that the weather forecast for the Goa holiday is looking good and you touch the nearby wooden table to ensure that it remains so.

Ok, so most of us have done some version of this. But we can clearly recognize (right?) that these are imagined causes.

For this essay, let’s keep superstitions like these aside – I want to focus only on causes that we think of as ‘real’. Basically the kind of examples that we discussed in the earlier table – like the Coinbase Pitch, Bezos’ statement, Sequoia’s deck, or the business review presentation.

In such examples, the causal connections may seem to have been arrived at with careful consideration after empirical observations and logical thinking.

Right?

Even if they have, it is critical for us to check for the validity of these causal statements – given we have so much riding on them. To do so, we need to think with a calm, clear logical mind to test the soundness of the argument.

We aren’t as logical as we believe

I’ve written in the past about Aristotle’s Ethos-Pathos-Logos framework10. Many ‘left-brain’ folks would assume that they are naturally adept at logos. They’d think – “No one can accuse me of relying too little on logic and too much on emotion. If at all, it’s the other way around.”

That might be the case – most of us struggle with understanding and communicating emotions (we especially struggle with empathy). But here’s the worse news: We aren’t as strong at logical thinking as we believe.

A lot of this, of course, has to do with the cognitive biases that affect all of us. But there’s another issue.

We have never been formally taught how to think logically. Which is a shame. Because ancient philosophers (especially the Greeks like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle) had thought about this problem just about, oh, twenty-three hundred years ago… and created simple techniques for logical reasoning.

A fundamental logical reasoning framework

When you pick up the ‘Pyramid Principle‘ by Barbara Minto, you would expect to get tips on writing and presentations. You will. But the book is really about clear thinking.

And, when it comes to thinking clearly, there are two most fundamental inter-connected approaches11 – we use to reason from our facts and observations:

- Deductive reasoning12

- Inductive reasoning

The most watertight way of testing your causal thinking is through deductive reasoning. Here’s how it works:

- You have a Major Premise.

This is an irrefutable fact, which everyone agrees on. This is written as ‘All Xs are Ys‘.

- You then have a Minor Premise.

This is a fact that can be easily confirmed. Something like ‘A is an X ‘.

- Finally, there is a Conclusion

An opinion or decision that necessarily follows from the Major and Minor premise. In this case, it would be – ‘A is a Y‘.

An example will clear things out. I’ll start with a simple example that pays homage to where all this comes from:

- Major Premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor Premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

Let’s take another example:

- Major Premise: All students who are bright and study hard will pass the exam with distinction

- Minor Premise: Ria is a bright student who has studied hard

- Conclusion: Ria will pass the exam with distinction

In this example, you might be thinking – hang on… are those the only two factors? What if Ria loses concentration on the day of the exam? What if she has a nervous breakdown?

Good work! You are already stress-testing the Major Premise. This will help in the next section when we consider more examples.

You use this framework ALL the time

When I first came across deductive reasoning, I thought – ‘Hm, that sounds cute. But I don’t face these CAT-problem-like situations at my work. Who talks about Socrates and mortality in a client presentation?’

Oh, but we do. We use deductive reasoning all the time. Let’s take the ‘Action’ statements which our earlier examples implied13:

- You must invest in CoinBase

- You should not break up Amazon and let it be as it is

- You must choose a dynamic pricing strategy to increase sales

Where would these statements fit in the Deductive logic template? They are all ‘Conclusions‘ – telling the audience what needs to be done. (In our D-E-C-A framework14, they are ‘Actions’)

If we want to test their logical strength, all we need to do is work backwards and derive their Major and Minor Premise.

Here’s the Minor Premise for each of these conclusions:

- Coinbase is safe and trusted and has a user-friendly platform in the growing crypto-economy. (Conclusion: We must invest in Coinbase)

- Amazon has enabled extraordinary outcomes for all stakeholders, driven by its size. (Conclusion: You should not break up Amazon)

- The dynamic pricing strategy led to a 4X increase in sales. (Conclusion: We must adopt a dynamic pricing strategy)

Hm, that sounds logical enough. You might be tempted to respond: “Sounds great, these conclusions have enough backing (especially that third one). I’m sold”

Hang on though, we still need to derive the Major Premise for each of these. The Major Premise is the ‘irrefutable truth-like’ assumption that drives the other elements. Here goes:

- Major Premise: In the growing crypto-economy, you should invest in a crypto company if it is safe and trusted and has a user-friendly platform. (Minor Premise: Coinbase has a safe and user-friendly platform. Conclusion: You must invest in Coinbase)

- Major Premise: If a company has enabled extraordinary outcomes for all stakeholders, driven by large size, then they should not be broken apart. (Minor Premise: Amazon has enabled extraordinary outcomes for all stakeholders. Conclusion: We should not split Amazon).

- Major Premise: Any strategy that results in a significant increase in sales, should be replicated. (Minor Premise: The dynamic pricing strategy led to a 4X increase in sales. Conclusion: We must adopt a dynamic pricing strategy)

Note the certainty in the Major Premise. That is the nature of these assertions. They claim to be the unequivocal, irrefutable truth.

Major Premises are the unsaid assumptions that drive our opinions. On very rare occasions, they are spelled out aloud. But mostly, they lurk unexpressed in the deep recesses of our minds.

And here’s the key trick. We need to articulate these Major Premises. We need to put them out clearly on paper. Unless we do that, we aren’t able to reason logically. We are not able to ask the crucial question: Is this Major Premise true?

And guess what, it may not be. You may suddenly realize:

- When evaluating crypto-economy companies, (apart from safety and convenience) we may also need to look at the sector risk.

- When deciding about a large company (apart from its positive impact on all stakeholders) we may need to look at the potential negatives and whether it offers a net benefit.

- When deciding on the replication of our pricing strategy, we need to consider the context of the market and competition.

What have we done here? We are stress-testing the Major premise for a crucial property: MECE evidence. We are asking whether the Major Premise is true in all possible situations.

MECE, or “Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive” is a construct credited to (who else) Barbara Minto, who then further credits it to (who else) Aristotle. I’ve written earlier about how MECE thinking is crucial for answering tough questions. Being MECE means you have considered all possibilities in a comprehensive and non-muddled way when deriving the Major premise. Nothing has been left out.

This is not theory – let me illustrate with an example from my consulting stint.

Deductive logic real-life use case

Around 2009-10, a reputed industrial conglomerate based in Bangalore was entering the healthcare delivery space. They wanted to set up a large hospital focused on two specialties – orthopedics and neurosciences. They had already roped in a leading neurosurgeon to be part of the founding team. I was part of a management consulting team that was preparing the business plan and strategy for that venture.

Their remit to us was: Figure out how to make an ortho-neuro hospital work. We studied the data, and looked at several other such hospitals in the city, in other cities, and also in other states. And we finally came to a conclusion: it would not meet their financial goals.

Essentially, the group was not looking at this as a charitable venture. Their desire was to build a financially sustainable operation. Keeping that in mind, our message to them was: In order to make your hospital viable, you will need to include other specialties too. Especially cardiac care.

It was a tough sell – the founder and the neurosurgeon had almost made up their mind about the hospital’s configuration – they didn’t want to budge from the ‘Ortho-Neuro’ positioning… and we were just hired external consultants, working with them for the first time.

So we developed a Major Premise: No hospital in India that focuses only on orthopedics and neurosciences has met the financial goals that the client had.

We researched hospitals across several cities and built a case saying: Here’s a MECE list of the top Ortho-Neuro hospitals in the entire region. None of them are achieving the financial goals you have in mind. As against that, here are some numbers from other hospitals that also have other specialties, especially cardiac care. These are doing much better financially. Backed by this evidence, we managed to convince them to go with our suggestion.

Today that hospital is a leading multi-specialty center of excellence in the city – with an especially flourishing cardiac practice.

Which brings me to an important question – how is a Major Premise actually derived? It seems to be a statement which is taken as a gospel truth. Surely we should know its antecedents.

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time to introduce ‘Inductive Reasoning‘.

Many observations of the same pattern = Major Premise

We form Major Premises by carefully observing the world around us and discerning patterns. This evidence-based exercise is called ‘Inductive reasoning’ .

So in the hospital case, this is how we used Inductive reasoning:

- There are (say) 4 leading hospitals that have an ‘Ortho-Neuro’ positioning in the target region (let’s call them A, B, C, and D)

- None of the four hospitals – A, B, C, or D – are meeting the financial goals that the client had for their proposed hospital

- Therefore, (it is fair to say that): No hospital with an ‘Ortho-Neuro’ positioning can meet the financial goals that the client had

In real life, we do this inductive pattern-finding all the time – from standard stereotypes like ‘All Tamilians love curd-rice’ (not true), ‘All Punjabis are boisterous’, ‘Successful start-up founders are dropouts’ to nuanced observations like ‘Every time I use more than 10 slides, my audience loses interest halfway through the presentation’.

There are two common forms of Major Premise statements that we use to reason inductively:

1. If you are an X, you must be a Y

2. If you want to get X, you must do Y

a. As a Necessary condition, or,

b. As a Sufficient Condition

Let’s dive deeper into each of these statements.

1. If you are an X, you must be a Y (e.g. if you are a man, you are mortal)

In this case, the premise is formed by countless observations – where people have seen all Xs being Ys. These are usually definitive in the natural world (e.g. “if you throw an object from a height, it will fall down”). But even there, there are exceptions. E.g. “If you are a bird, you must be able to fly” sounds like a pretty solid Major premise for a third-century BC thinker. But we all know of flightless birds.

The Black Swan digression

Speaking of birds, the most famous example of the flaw in inductive reasoning involves a bird: The black swan.

In ancient times all swans were thought to be white, because that was the only colour of swan people came across. So ‘All swans are white’ seemed like a plausible statement.

Until, in 1697, Dutch explorers in Western Australia came across the ‘Cygnus Atratus’, commonly known as the Black Swan. Something that was thought of as impossible became normal.

In Fooled by Randomness15, Nassim Nicholas Taleb asks us to consider the following two statements:

Statement A: No swan is black, because I looked at four thousand swans and found none.

Statement B: Not all swans are white.

I cannot logically make statement A, no matter how many successive white swans I may have observed in my life and may observe in the future (except, of course, if I am given the privilege of observing with certainty all available swans). It is, however, possible to make Statement B merely by finding one single counterexample.

Incidentally, you’ll now see the flaw in my earlier example featuring the inductive statement ‘No Ortho-Neuro hospital can meet the client’s financial goals’. The right statement would be: ‘So far, no ortho-neuro hospital has been able to meet the client’s financial goals’, with the unsaid corollary: But a hospital may, in the future.

In his later book, The Black Swan16, Taleb uses the bird’s metaphor to describe unprecedented events (like the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, the 2007 Financial Crisis) that seem impossible before they occur but inevitable after the event:

What we call here a Black Swan… is an event with the following three attributes.

First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’. Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

I stop and summarize the triplet: rarity, extreme ‘impact’, and retrospective (though not prospective) predictability. A small number of Black Swans explains almost everything in our world, from the success of ideas and religions, to the dynamics of historical events, to elements of our own personal lives.

This issue – of being unable to come up with definitive universal truths based on past observations alone – is called the Problem of Induction and has been raised by thinkers like David Hume as well as ancient Indian and Greek philosophers.

Despite these philosophical reservations, our minds don’t seem to have gotten the memo. We make such ‘All Xs are Ys’ generalisations all the time. For instance, we may think – ‘All people of X community/ region/ background exhibit Y characteristic’ (e.g. All Indians are good at computers).

In doing so, we need to be careful not to fall into the stereotyping trap. We need to be aware that even statements that seem to be irrefutable Major Premises can be disconfirmed with just one or two contradictory examples. This may not change the fundamental belief of ‘All Xs are Ys’, but at least help temper its certainty.

Let’s now consider the second type of Inductive Reasoning statement.

2. If you want to get X, you must do Y

This second type of Major Premise is used more commonly in the world of business and life in general. E.g. consider the following statements:

– To have a successful startup, you need a co-founder

– To tell a compelling story about your company or product, you must start with the ‘why’;

– By changing your body posture, you can change your audience’s reaction

Now there are two sub-variants of this. The first one exhibits lesser conviction:

a. If you want to get Y, you must do X as a necessary condition

Take the premise: ‘If you want the strategy project to succeed you must pick a firm which has vast experience in the topic’. Now that sounds pretty logical. But even here, you may find contradictory exceptions. Perhaps a colleague recollects an instance from 2016 when he went with a rookie team for a consulting project and they delivered exceptional results. That’s a rebuttal of your Major Premise.

b. (The stronger statement) If you want to get Y, all you need to do is X (as a sufficient) condition

This one is trickier to prove. You might think, ‘If you want to pass, you must be bright and study hard’ is pretty sufficient, but then other factors – like studying smart, and taking care of your health – may also play a part.

To pick holes in a Major Premise like this, all you need to do is to find evidence that other factors also matter.

The hidden ingredient and the source of humility

Some of you may be thinking, “Hang on, you’ll never find something that is 100% true. There will always be contradictory evidence to any Major Premise you make.”

Exactly. It’s time to introduce the secret, unstated ingredient that powers most of these logical statements.

Probability.

When we say, “If you are bright and study hard, you will pass the exam”, what we mean is “If you are bright and study hard, there are very high odds that you will pass the exam”.

I’ve written earlier about our troubles with Probability. We struggle to incorporate it in our opinions, but probability is the only certainty in an uncertain world. We have to think of statements in probabilistic terms rather than unequivocal terms. And we have to seek contradictory evidence that may disconfirm our hypotheses.

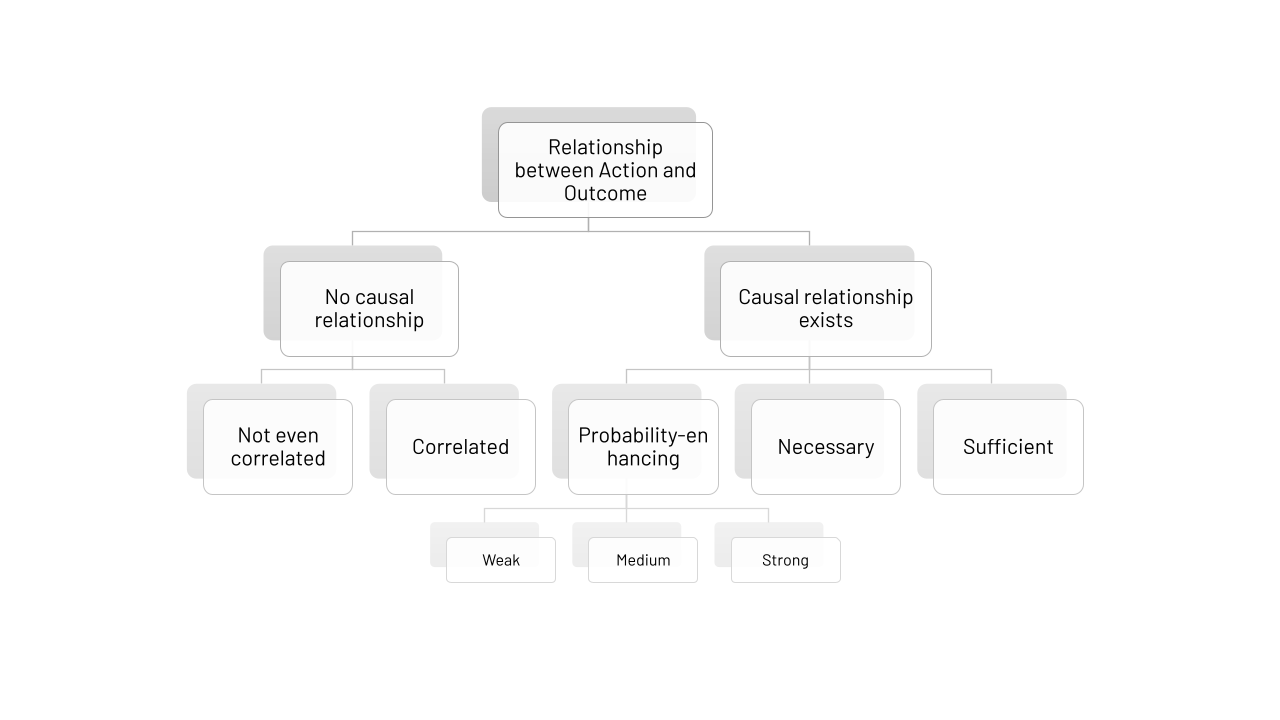

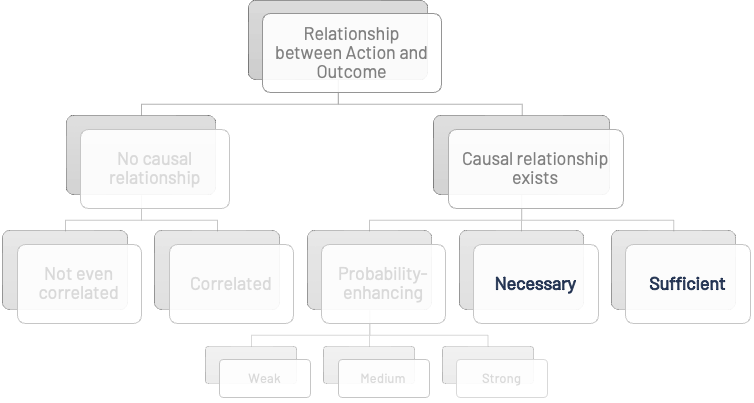

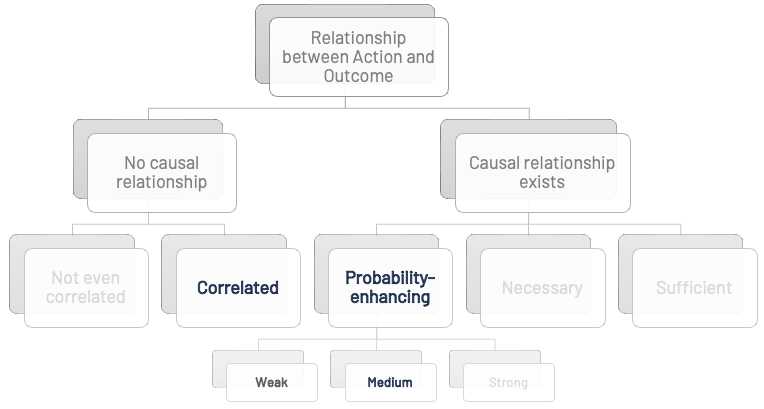

Here’s a good way to think about the causal relationship between an action and outcome – the strength of the relationship increases from the left to the right of the frame.

Probably, You should temper the conviction that you are right

While in theory, we can run a full ‘deductive logic’ approach for the important decisions in life, let’s be real: most of us are unlikely to have the time and inclination to do so. For one, it is almost impossible to get 100% MECE evidence to corroborate the Major Premise. (Say, you are evaluating the premise that WordPress is the right platform to build your website because it loads faster. While you might get some inputs from review sites, you surely cannot look at ALL previous installations of WordPress and their loading speeds vis-à-vis competing website builders). And two, even if you manage to do that, you’ll still be left with the Black Swan problem of induction.

In other words, while the ancient deductive-logic framework is theoretically the most robust way of testing your causal theories, it is not practically feasible in most instances.

Since ancient times, people have been looking for reliable tools and techniques to find the real cause. But this hunt for causality is made fiendishly complicated because of a major hurdle: imposters.

3. CORRELATION AND CONTEXT: TWO IMPOSTERS OF CAUSALITY

Outside of the physical sciences, most causal connections are not ‘sufficient’, ‘necessary’, or even strongly probabilistic. Though we may believe otherwise, most causal relationships in life are weak-to-medium probability-enhancing factors, typically being one among a complex array of factors.

To measure the impact of a specific action on a desired outcome has been humanity’s Holy Grail. Specifically, we have grappled with the intractable puzzle of finding a fool-proof approach to understand the true causal relationship between actions and desires. This puzzle to find the real ‘C’ is made fiendishly difficult because of three imposter ‘Cs’ (two of which we study in this chapter):

- Correlation – A situation where the factor being studied just happens to be correlated with but not causing the outcome

- Context – The presence of internal and external contextual factors (both tailwinds and headwinds) that would have influenced the outcome in addition to the main factor being studied

- Chance – the likelihood of a chance occurrence, which may not repeat, even under similar conditions

Let’s apply this to a simple scenario. Say, you went on a short vacation and came down with a bad cold and cough. You take a cough syrup for the ailment, complete your vacation, and come back home. Within a few days, your nose clears and the cough goes away. You advertise the benefits of the medicine to all and sundry.

But you might be falling into the classic cause-effect trap.

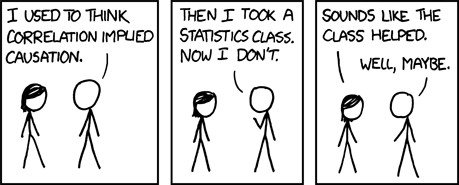

Repeat after me: Correlation is not causation

This is the first lesson that every statistics course starts with. The fact that you took a cough medication may have nothing to do with your recovery. It was just happenstance, with the real recovery caused by something else.

Correlations masquerading as causations abound and have been confounding storytellers for ages. For instance, across ancient cultures, comets have been derided as harbingers of doom, people obsess over the arbitrary positions of the stars relative to the sun and moon at the time of their birth, and entire careers have been made on the placement of random objects at various positions in the house.

These are not just the naïve beliefs of our ancient ancestors. In recent examples, take the case of vaccine hesitancy. As per the CDC, people who did not take any vaccine were 14X more likely to die as compared to those who took the updated COVID-19 vaccine. And yet about 15% of adults chose to remain unvaccinated resulting in a significantly higher death rate.

Why this vaccine hesitancy? One possible driver is the narrative connecting vaccines with autism in children.

In a 2017 paper, Dr. Michael Davidson writes (emphasis mine):

In many regards, vaccines—and in particular, those for mumps, measles, and rubella (MMR) – have the makings of a cause-effect myth. The notion that “if B follows A, then A is probably the cause of B” is the most common misinterpretation of causality. The MMR vaccine is administered to 12- to 18-month-old children. At this age, the first signs of an impending developmental condition, such as autism, start creeping in and become noticeable. The idea that “vaccine precedes event, hence vaccine causes disease” fits the cognitive bias to search for patterns and is much more comforting than the notion of coincidence or bad luck. A simplistic explanation, such as the claim that the emerging but still weak immune system of the toddler is overstimulated and damaged by the vaccine, adds credibility to the cause-effect sequence. At the same time, the current and future benefits of the vaccine are much more difficult to imagine and process. Whereas intervening to treat an existing condition is easy to understand, the notion of prevention is intangible. Paradoxically, the decrease in vaccination is the result of the success of vaccines in eradicating the respective illnesses. The benefit of injecting a substance to prevent a disease that neither the subject nor anyone around her has ever seen, such as measles, is difficult to comprehend. However, almost everyone has met a person affected by autism, and the prospect of having it is scary.

Humans are pattern-seeking beings and we have been doing it for millennia. Sometimes we see patterns when none exist17 (e.g. the zodiac), and create connections when none exist (like comets being harbingers of doom or vaccines causing autism).

This tendency also occurs in business. Consider the $50 M that eBay was spending annually on paid search ads as cited in this Harvard Business Review article. eBay’s analysis showed that where ads were higher, sales were higher. However, a more thorough analysis by three economists came up with a different conclusion – the ads were mostly a waste, especially for existing customers of eBay who had completed at least three transactions on the site in the previous year.

Here’s a key paragraph by the author of the HBR article

The targeted customers’ pre-existing purchase intentions were responsible for both the advertisements being shown and the purchase decisions. eBay’s marketing team made the mistake of underappreciating this factor, and instead assuming that the observed correlation was a result of advertisements causing purchases. Had eBay explored other factors that may have been responsible for the correlation, they would likely have avoided the mistake.

Right at the beginning of this essay, we spoke about Ankit (my workshop participant) and his causal belief about his division’s sales spike being driven by the ‘dynamic pricing’ strategy. This was a classic case of correlation but no causation.

In fact, in this specific scenario, it was possible to mathematically determine the factor which drove sales up using an accounting technique known as ‘variance analysis’. In this technique, the factors that drive sales are isolated to determine the impact of each element on the final outcome.

On applying variance analysis in Ankit’s case, we found that the sales increase was mainly due to a change in the ‘product-mix’ (and to some extent also volume increase); the pricing change had very little to do with it.

Despite being a leader who dealt with that business day in and day out, Ankit had a mistaken causal notion about what drove the impact. That’s how deceptive correlation can be.

The conflation of correlation and causation is so well understood, that at one point in time, it was used by the tobacco industry18 to stall warnings around smoking:

In the spring of 1965, a US Senate committee was pondering the life-and-death matter of whether to put a health warning on packets of cigarettes. An expert witness wasn’t so sure about the scientific evidence, and so he turned to the topic of storks and babies. There was a positive correlation between the number of babies born and the number of storks in the vicinity, he explained. That old story about babies being delivered by storks wasn’t true, the expert went on; of course it wasn’t. Correlation is not causation. Storks do not deliver children. But larger places have more room both for children and for storks. Similarly, just because smoking was correlated with lung cancer did not mean – not for a moment – that smoking caused cancer.

This was a case where there was a causal relationship – between smoking and lung cancer – but the tobacco industry smartly used the subterfuge of correlation to postpone the much-needed legislation against smoking.

This is, of course, a rare situation – in most cases, we are prone to see causal relationships where there are none. But even when there might be a causal relationship between Action and Desire, we make a different mistake most of the time. We over-estimate the consistency and quantum of the impact of the factor that we are studying and either ignore or under-weight the impact of other factors. I call these contextual factors.

Context: Other factors – internal and external – which impact the outcome

Every action occurs in a certain context – a combination of external and internal factors that influence the outcome. In statistics, this is called a ‘confounding variable’ a hidden or unseen factor that influences the end outcome.

For instance, in our cough-and-cold example, let’s say that the vacation destination was a dry hillside town and your home is a humid seaside city. Perhaps it was the change in weather – an external contextual factor – that was instrumental in clearing your nose and throat.

Or maybe, your immune system was better equipped than others to deal with the virus and could flush it out faster (which is why your spouse’s cough lasted longer despite taking the same medicine). We could categorise this as an internal contextual factor.

Let’s dive deeper into context-based factors

External contextual factors

A close friend of mine (let’s call him Sam) was lamenting to me about his discussions with an independent director (Joe) at his company. Whenever Sam would present some results which were less than stellar, Joe (who had been the CEO at a mid-sized Indian consumer goods company through the 1990s and early 2000s) would have a ready story: “You know, when I was the CEO at ABC, we did X and got great results”

Sam would smile as he heard Joe wax eloquent about his earlier exploits, but would be thinking, “Yes Joe, but you were in a high-growth economy with strong tailwinds – every company in your sector was growing”

Now surely, there might have been many differentiated actions that Joe took for which he deserves rightful credit. But to ignore the crucial external element – of the economy tailwinds – is not fair. Especially when the current conditions may not be as conducive.

It’s not just external factors – even our own genetics, upbringing, luck, and other advantages have a major role to play in our outcomes.

Internal contextual factors

Privilege is an internal context factor. As Ed Yong writes in the National Geographic:

Ask successful people about the secrets of their success, and you’ll probably get answers like passion, hard work, skill, focus, and having great ideas. Very few people, if any, would reply with “privilege and luck”. We’re often blind to these factors and they make for less inspiring stories. But time and again, we see that the advantages that give us a head-start and the accidents that ease our path can make or break a career.

Luck can be of two types – one, the ovarian lottery, i.e. where you were born; and two, the series of incidents that happen to you after birth. Often the sheer accident of birth can be a major determinant of what we achieve in life.

Celebrated investor Warren Buffett has openly acknowledged the advantage he derived from being born a white male in America in the 1930s. During the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholders Meeting in 1997, Buffett spoke about the importance of the “ovarian lottery”.

When Charlie Munger and I were born, the odds were 30-to-1 against being born in the United States. Just winning that portion of the lottery was an enormous plus. We wouldn’t be worth a damn in Afghanistan. We won it partially in the era in which we were born by being born male. When I was growing up, women could be teachers or secretaries or nurses and that was about it.

The ovarian lottery he said is “the most important event in which you’ll ever participate. It’s going to determine way more than what school you go to, how hard you work, all kinds of things.”

For a rare and powerful example of an Indian leader acknowledging the role of external context in his success, check out from minute 14:11 to 18:50 of this video featuring Rajiv Bajaj (CEO of Indian automotive giant, Bajaj Auto). In the interview, he shares an anecdote about how his great-grandfather’s life and those of further generations were transformed by a freak incident in his ancestral village in the state of Rajasthan.

Here’s the incident in brief: In 1894, in a village in Rajasthan, a four-year-old child from a poor family was playing outside in the courtyard in the blazing sun. A rich merchant, named Bachharaj Bajaj, was going by in his fancy horse carriage. Mr. Bajaj, who was childless, saw this boy and felt that there was something special about him. So he walked up, knocked on the door, and asked the boy’s mother “Whose child is this?”

In a manner of speaking, she said, “Thaaro hi hai” in Marwari (meaning, he is like your child only). Mr. Bajaj said, “Ok, then I’m taking the child”.

After the initial shock, the parents were convinced to give up their son. As a token of his gratitude, the merchant had a well installed in the village.

More importantly, that four-year-old boy grew up as Jamnalal Bajaj, the founder of the Bajaj group of companies which reached a staggering $100Bn in market value in 2021.

Today when Rajiv Bajaj looks at himself as the CEO of the vast Bajaj Auto conglomerate, he is cognizant of this accident of history which gave his great-grandfather the opportunity to maximise his inherent potential and cement a strong legacy for his family.

So: Correlation and Context are two formidable imposters that complicate the hunt to find the real cause. But humans have not given up the chase. And especially in the last century or so, we have created a few specialized tools that aim to attain this Holy Grail.

4. MODERN TOOLS FOR SOLVING THE CAUSAL PUZZLE

Will the real cause stand up, please?

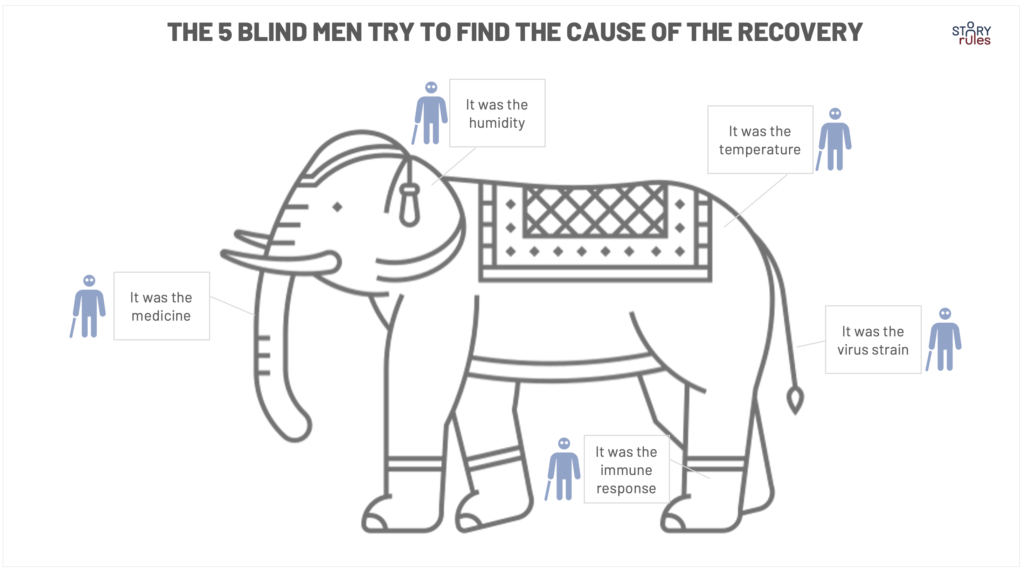

Let’s get back to our cough-and-cold example. What was the real factor that caused the improvement:

- The external context of the move from dry hills to the humid coast OR the specific virus strain that you caught

- The internal context of the body’s immune system

- The specific action of taking the medicine

Specifically, from an action point of view, was the medicine a detractor, mute spectator, marginal actor, or the main actor?

It seems almost impossible to know. But medical professionals have been working on this question since time immemorial.

In fact, almost all medicine is a form of experimentation that tests the premise: If we take X/do Y, does it cure Z?

While there had been several previous attempts at controlled medical experimental treatments to determine causality, in 1947, the world of medicine achieved an important breakthrough: randomization.

In 1947, the UK’s Medical Research Council (MRC) wanted to check the efficacy of the newly discovered antibiotic streptomycin against tuberculosis. Normally this would have been done by administering the new drug to a group of patients, whilst simultaneously keeping a ‘control’ group to whom either no drug was given or a placebo was administered. However, this approach had a weakness. If the participants chosen for the trial were inherently (because of internal context factors) more likely to get better, then it could be difficult to isolate the impact of the medication.

Which is where, in the streptomycin study, the MRC added a crucial step: they randomized the participants in the two groups with the help of a statistician named Sir Austin Bradford Hill.

Here’s how the study’s Director, Dr. P D’arcy Hart, describes it:

The trial proceeded from 1947. The small amount of streptomycin available made it ethically permissible for the control subjects to be untreated by the drug – a statistician’s dream. The trial had two main results. Firstly, it showed that streptomycin was effective against pulmonary tuberculosis, but there was evidence of some toxicity and acquired drug resistance (not easily obtainable from the American studies). Secondly, the trial heralded the general conversion of clinical scientists to randomisation.

The UK MRC’s 1947 streptomycin trial is regarded as the world’s first published RCT: Randomised Control Trial.

In the years of experimentation that followed, medical science has now arrived at a widely accepted approach to answer the causality question: The DBRCT

DBRCT stands for Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial OR Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomised Clinical Trial. Let’s unpack that acronym:

- An experiment or trial: After all the thinking, hypothesizing, and discussions, finally, medical results are observed by trial.

- The presence of ‘control’: If everyone is administered the treatment, one wouldn’t know if it works versus doing nothing. The control group is chosen to be similar to the treatment group in all respects except getting the medication.

- Randomized: To ensure that no bias creeps in while deciding the formation of the treatment and control groups, the composition is randomized, i.e. chosen via a random sampling process from the entire population. Of course, this assumes that basic statistical techniques of figuring out the right sample size, diversity, etc. are observed.

- Placebo: To ensure that the control group is not psychologically impacted because of not being given the cure, they are given a placebo – an ineffective substance that may seem like a cure for them. This way, if the condition is cured with a placebo, it indicates that the treatment does not have any additional benefit

- Double Blind: Finally, neither the patients nor the caregivers should know who is part of the treatment or the control groups, to avoid any psychological impact of the same.

Today the DBRCT is at the heart of the pharmaceutical R&D process and no medicine can be launched without going through the lengthy and critical clinical trials process.

Of course, the process is not foolproof, and there are several issues with clinical trials. But DBRCTs remain the gold standard process for innovation.

(Side note: The DBRCT is just a key milestone in the evolution of the ‘Scientific Method’ – the name given to a set of techniques used by philosophers, scientists, and other thinkers to learn more about our world. The key components of the Scientific method are:

- Forming of hypotheses and theories

- Systematic experimentation and observation to test them

- Using inductive and deductive reasoning to derive conclusions

- Rinse and repeat

This essay does not intend to get into the history of the Scientific Method. Instead, we will restrict our attention to important examples (like DBRCTs) of this crucial approach for finding causality).

Alright, so medicine has solved the causality puzzle to some extent. What about other fields which may not be from the hard sciences?

Causality in Economics (A Tale of Two Nobels)

If there is one specialized field where non-experts have strong opinions it is economics.

You won’t find laypeople commenting on the right corrosion inhibitors for ethanol blended gasoline (chemistry), or the right dimensions for railway bridges (physics/engineering), or the right fertilizer mix for a crop of bananas (plant biology). But when it comes to economics, everyone has an opinion on what the government should do. That opinion is based on strong causal relationships in our minds. Relationships that may be deeply flawed.

Thankfully, real economists have to show more rigour in expressing their opinions.

In 2019, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, and Michael Kremer won the Nobel Prize in Economics for their pioneering work of using randomized control trials to evaluate various policies in development economics.

This year’s Laureates have introduced a new approach to obtaining reliable answers about the best ways to fight global poverty. In brief, it involves dividing this issue into smaller, more manageable, questions – for example, the most effective interventions for improving educational outcomes or child health. They have shown that these smaller, more precise, questions are often best answered via carefully designed experiments among the people who are most affected.

Why did they take this approach? Here’s how the Nobel Academy’s background paper describes their rationale:

Why did the researchers choose to use field experiments? Well, if you want to examine the effect of having more textbooks on pupils’ learning outcomes, for example, simply comparing schools with different access to textbooks is not a viable approach. The schools could differ in many ways: wealthier families usually buy more books for their children, grades are probably better in schools where fewer children are really poor, and so on. One way of circumventing these difficulties is to ensure that the schools being compared have the same average characteristics. This can be achieved by letting chance decide which schools are placed in which group for comparison – an old insight that underlies the long tradition of experimentation in the natural sciences and medicine. In contrast to traditional clinical trials, the Laureates have used field experiments in which they study how individuals behave in their everyday environments.

Essentially, RCTs enable the researchers to control for the Context (to the extent possible) and answer narrow Action-Desire questions. Their use has been progressively accepted as a tool for policy evaluation, especially since 2000. As of March 2023, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has a database of 1,178 randomised evaluations across 95 countries.

But wait, there’s more. Just two years after the Nobel to Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer, the 2021 Economics Nobel was awarded to David Card (“for his empirical contributions to labour economics”) and Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens (“for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”).

Here’s a fascinating extract from the Press Release by the Nobel Academy:

Many of the big questions in the social sciences deal with cause and effect. How does immigration affect pay and employment levels? How does a longer education affect someone’s future income? These questions are difficult to answer because we have nothing to use as a comparison. We do not know what would have happened if there had been less immigration or if that person had not continued studying.

However, this year’s Laureates have shown that it is possible to answer these and similar questions using natural experiments. The key is to use situations in which chance events or policy changes result in groups of people being treated differently, in a way that resembles clinical trials in medicine.

The background note by the Academy addresses an important limitation of randomized control trials – we cannot deliberately experiment with someone’s future for testing a policy idea:

One way of establishing causality is to use randomised experiments, where researchers allocate individuals to treatment groups by a random draw. This method is used to investigate the efficacy of new medicines, among other things, but is not suitable for investigating many societal issues – for example, we cannot have a randomised experiment determining who gets to attend upper-secondary school and who does not.

In such situations, the economists realized that a great source of learning about causal relationships would be ‘natural experiments’ – situations arising in real life that resemble randomized experiments. For instance, in April 1992, the state of New Jersey in the US decided to raise hourly minimum wages from $4.25 to $5.05, an 18% increase.

Conventional wisdom was that this should have led to a decrease in employment (as price goes up, demand goes down). However one couldn’t just do a simple pre/post comparison here – what if there was a general business slowdown in the area, which led to a decrease in employment?

In order to properly evaluate the impact, one would need to compare with a ‘control’ – i.e. a world where minimum wages had not been increased. This is where the researchers widened their lens and found a natural control – the neighbouring state of Pennsylvania. They focused on employment in fast-food restaurants, an industry where pay is low and minimum wages matter. When they compared the impact on the two states, they found that there was no impact on employment in New Jersey (in fact it did better than Pennsylvania) despite the increase in minimum wage19.

So let’s step back and examine the scientifically accepted tools we have at our disposal to evaluate causality:

- Deliberate RCTs

- Natural experiments

Admittedly, these ‘gold-standard’ tools may not be widely usable at work and in life. RCTs are primarily suited to the medical field and to narrow, specific questions in fields like development economics. And while natural experiments offer fascinating grounds for the study of complex questions such as monetary policy (you know which experiment I am talking about), they are not exactly in your control.

But we can apply their ethos, their core driving principles to the decisions that we take in life.

In fact, we already do. In many workplaces, especially since the 2000s, we have been using a revolutionary new technique that is now a staple at large organizations evaluating the effectiveness of several micro (and some macro) decisions they need to take, especially for products sold online.

I’m talking about the A/B Test.

A/B Tests: The hidden causality-finding tool you might already be using

You’ve possibly used A/B Testing (or the more formal name, Online Controlled Experiments) several times at work. Or perhaps your company’s marketing team is a regular user.

The tool has been around for more than 100 years and was pioneered by advertising campaigns to check the efficacy of different messages. In today’s age, A/B tests are almost exclusively done online and involve displaying several versions of a product, usually simultaneously, to different users who are selected randomly.

For example, say you want to increase the signups to a form on your website (Desire), but aren’t sure what layout will work best (Action). Instead of hypothesizing endlessly or doing user surveys, you could run a controlled experiment and find out which solution is more optimal.

The $60M button

In 2007, a rising Democratic Senator called Barack Obama gave a talk at Google as part of his upcoming 2008 Presidential campaign. This inspired a young engineer named Dan Siroker to leave Google and join the Obama campaign as Director of Analytics.

One project Dan worked on was the main campaign page. Here’s how the original page looked:

Dan’s team tested twenty-four iterations of this page with different visitors. So each visitor would be randomly shown a different version of the campaign page. With over 310,000 visitors to the site, each page was shown to around 13,000 visitors.

The results were significant – the winning combination (depicted below) did 40% better than the original.

Here’s how Dan (who later wrote a book about the craft of A/B Testing) summarises the impact on his company’s blog:

If we hadn’t run this experiment and just stuck with the original page that number would be closer to 7,120,000 sign-ups. That’s a difference of 2,880,000 email addresses. Each email address that was submitted through our splash page ended up donating an average of $21 during the length of the campaign. The additional 2,880,000 email addresses on our email list translated into an additional $60 million in donations.

Of course, as we have learned earlier, it may be erroneous to attribute all of the ‘lift’ to the new layout. Maybe there were other contextual factors (such as Obama’s growing popularity) and perhaps the older layout may also have improved its signup rate. Also, assuming the same average rate of donations may be a flawed premise. Still, one can argue that the new layout did have a significant positive impact on the campaign.

Your friendly neighbourhood tech giant does this

A/B testing is now a mainstream technique used by several leading organizations. In December 2018, thirteen tech giants (Airbnb, Amazon, Booking.com, Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Lyft, Microsoft, Netflix, Twitter, Uber, Yandex, and Stanford University) met in Sunnyvale, California for the first Practical Online Controlled Experiments Summit. In the year before the summit, just these thirteen organizations had conducted more than one hundred thousand experiments.

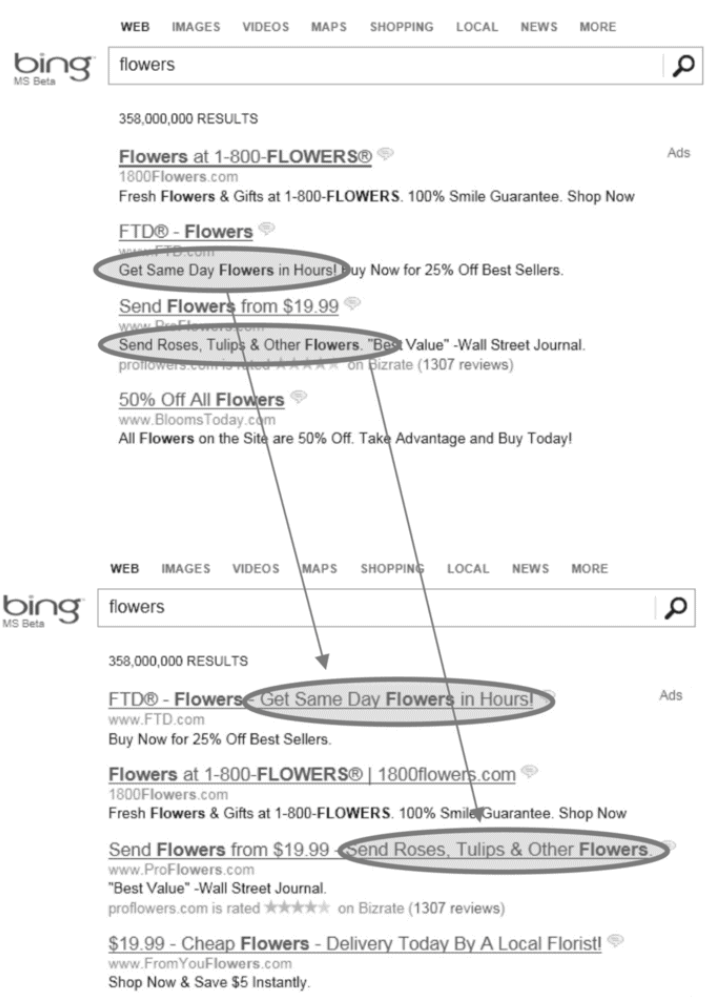

One well-known experiment happened in 2012 at Microsoft. An employee working on Bing, their search engine had an idea about increasing the title line of ads on the platform by taking in some text from the first line below the title.

Source: From ‘Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments: A Practical Guide to A/B Testing’ by Ron Kohavi, Diane Tang, Ya Xu

It seemed like a trivial change and unfortunately got lost among the many ideas that were being considered at the time. Six months passed. A software developer decided to try out the idea since it was easy to code. He then ran it as an A/B test, showing only some users the new version.

In just a few hours an alert was triggered by the system – that the revenue generated by this version was too high and there might be some double billing or other discrepancy.

Due checks were made and the team came to a stunning realization: the revenue increase was valid and was 12%, translating to a massive $100M annualized revenue impact in the US alone (without significantly hurting key user-experience metrics).

A simple experiment that took a few days of work from one engineer had resulted in a $100M annual upside.

Admittedly these kinds of events are rare (once every few years, as per the authors). However, by doing several such experiments on a regular basis, organizations can unlock significant value.

In the years and decades ahead, the pace and quantum of such controlled experimentation will increase by leaps and bounds fueled by AI.

To sum up: Through centuries of experimentation, humankind has figured out the use of several causality-finding tools:

- RCTs – whether used in medical experiments or in development economics

- Natural experiments – which offer a control to test against a ‘natural’ control

- A/B tests – which isolate the impact of specific actions and negate the contextual elements.

But even after accounting for contextual factors, there’s one aspect that we cannot anticipate or plan for: The third imposter ‘C’ – chance or probability.

5. RECOGNISING CHANCE: THE BIGGEST IMPOSTER OF CAUSE

Going back to the medical example, what do you think really cured your cold and cough:

- The medicine you took

- Your immune system

- The external environment change

- Or were these elements all random and may not give the same result if repeated again in the same measure?

Honestly, we don’t know. Perhaps in that visit, the specific virus that you contacted coupled with the temperature and humidity conditions were such that you got a milder version of the illness. Maybe if you go to the same place again, there might be a minor change in any of the factors, which might change the equation. Or perhaps you were undergoing some stress due to a few rough days at work, which resulted in a compromised immune system.

In short, we need to acknowledge the role of probability in your recovery and understand that in a future instance, doing the same ‘X’ may not give you the desired ’Y’.

Of course, you might say that ‘chance’ is nothing but ‘context’ in a different name. The temperature and humidity, the type of virus, the stress you were undergoing – can all be tagged as contextual factors.

But if there are so many variables influencing just a simple flu, imagine the thousands (millions?) of such contextual factors that could impact major occurrences – like getting funding for your startup or getting selected for an IPL team. The ‘input variables’ could play out across decades to influence the final outcome. It might be almost impossible to isolate the exact impact of a specific variable.

And so, for an outside observer, the final result may look like a random probability-driven occurrence.

To paraphrase: One could say that context is what is visible while chance is invisible context.

Let’s take a work-based example to make this clearer. What’s the most important factor driving success in life? You might say: Hard work.

I asked ChatGPT to give me 5 specific examples of hard work being the key to success. Here’s what it came up with (emphasis mine):

- Athletes: Athletes who put in consistent and focused hard work are more likely to achieve success. For example, Olympic champion Michael Phelps swam for up to 6 hours a day, six days a week, for years in order to become one of the most decorated athletes in history.

- Entrepreneurs: Successful entrepreneurs often work tirelessly to build their businesses. For example, Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, worked long hours, often sleeping in his office and pushing his team to work hard, which ultimately led to Amazon’s success.

- Musicians: Musicians who work hard on their craft are more likely to achieve success. For example, Beyoncé is known for her relentless work ethic, putting in long hours of practice and rehearsals to become one of the most successful and influential musicians of all time.

- Scientists: Scientists who work hard and remain persistent in their research often make breakthrough discoveries. For example, Marie Curie worked tirelessly to discover radium and polonium, making her one of the most successful scientists in history.

- Writers: Writers who put in the hard work of writing consistently and honing their craft are more likely to become successful. For example, J.K. Rowling wrote for years before publishing the first Harry Potter book, which eventually led to her becoming one of the best-selling authors in history.

Overall, hard work is often the key to achieving success in any field. It requires dedication, persistence, and consistent effort, but the rewards can be great.

Phelps, Bezos, Beyonce, Curie, Rowling. Impressive list. It seems convincing too, right?

Except, the causal relationship it is implying – that if you work hard, you will (most likely) be successful – is flawed.

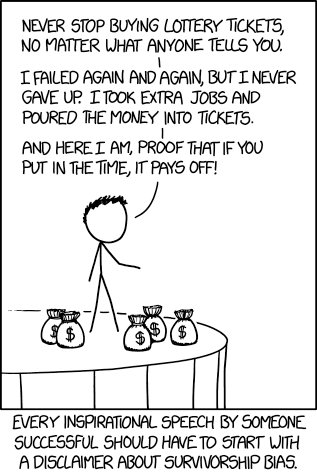

These examples are classic instances of survivorship bias – when we draw all our lessons from those who ‘survived’ or succeeded, but not those who ‘died’ or failed.

This blog post by entrepreneur Jason Cohen does a good job of summarizing the famous World War II story that exemplifies survivorship bias:

During World War II the English sent daily bombing raids into Germany. Many planes never returned; those that did were often riddled with bullet holes from anti-air machine guns and German fighters. Wanting to improve the odds of getting a crew home alive, English engineers studied the locations of the bullet holes. Where the planes were hit most, they reasoned, is where they should attach heavy armor plating. Sure enough, a pattern emerged: Bullets clustered on the wings, tail, and rear gunner’s station. Few bullets were found in the main cockpit or fuel tanks.

The logical conclusion is that they should add armor plating to the spots that get hit most often by bullets. But that’s wrong. Planes with bullets in the cockpit or fuel tanks didn’t make it home; the bullet holes in returning planes were “found” in places that were by definition relatively benign. The real data is in the planes that were shot down, not the ones that survived.

This is a literal example of “survivor bias” — drawing conclusions only from data that is available or convenient and thus systematically biasing your results.

Going back to the ‘hard work’ examples shared by ChatGPT, let’s consider the following:

- The world’s 10,000th-ranked swimmer might possibly be working as hard as Michael Phelps.

- You might have come across several founders who worked their butts off, slept in the office, and pushed their teams, without getting Bezos’-level of success.

- Many “unsuccessful” musicians are known to put in long hours in practice and rehearsals.

- The same stories can be found for scientists and writers.

But we tend to look at (and draw lessons from) only the ‘survivors’ not the ‘planes that did not come back’.

The point is: At best hard work might be a necessary (hygiene) condition for success – sometimes not even that. But if you read most accounts of successful persons, they might give you the impression that it is all that you need.

If you are even a casual reader of Twitter (or other social media platforms), you’d recognise the typical ‘success lessons’ thread. A set of tweets where the writer says: “I (or someone else) was wildly successful in achieving X; (if you want similar success yourself), you need to do Y”

|  |

| Source:Tweet thread by Sam DeBrule | |

|  |

| Source: Tweet by Colossus | |