The art and science of insights

Welcome to my content recommendations and reviews for Dec-21: a book, a podcast, articles and a video.

Let’s get started.

1. Book

a. ‘Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights’ by Gary Klein

Two cops were on a routine patrol when they saw something unusual.

Here’s how the author describes what happened next:

As they waited for the light to change, the younger cop glanced at the fancy new BMW in front of them. The driver took a long drag on his cigarette, took it out of his mouth, and flicked the ashes onto the upholstery.

“Did you see that? He just ashed his car,” the younger cop exclaimed. He couldn’t believe it. “That’s a new car and he just ashed his cigarette in that car.”

That was his insight. Who would ash his cigarette in a brand new car? Not the owner of the car. Not a friend who borrowed the car. Possibly a guy who had just stolen the car.

As the older cop described it, “We lit him up. Wham! We’re in pursuit, stolen car. Beautiful observation. Genius.”

That young cop had an ‘insight’ – an A-ha moment – which led him to identify and apprehend a car thief.

We get insights all the time. Insights that help unknot tricky problems. Insights which enable us understand the world better. And insights which help us do better at work and in life.

But do we ever stop to think and wonder: Hey, how am I actually getting this insight? And can I do something to actually increase my insights?

Luckily for us, Prof. Gary Klein, a cognitive psychologist who has studied the science of decision-making in real-world situations, decided to do a deep-dive into the world of insights.

First up, his definition of an insight is really simple yet powerful: ‘An insight is an unexpected shift to a better story‘.

I had come across this definition in an earlier book I had reviewed (Effective Data Storytelling by Brent Dykes) and had then gotten inspired to pick up Klein’s book.

I also liked the way Klein frames why it is important to encourage better insight-generation. So, insights are supposed to aid decision making. And in the world of decision-making, the last 20-odd years have been dominated by the field of behavioural science, especially focused on cognitive biases.

The avalanche was kicked off by the work of psychologists Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky (Kahnemann won the Economics Nobel in 2002), and has been carried forward by several luminaries, including another Nobel laureate, Richard Thaler. Several books have been written on the topic – from the magisterial ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, to the bestsellers ‘Predictably Irrational’ by Dan Ariely and ‘Nudge’ by Richard Thaler. There have also been mass-market paperbacks such as ‘The Art of Thinking Clearly’.

All of these works have focused on one aspect of human thought: our propensity to make systematic errors of judgement in decision-making. These errors are called cognitive biases and there is a long list of them.

Gary Klein thought these get too much importance. He wanted to turn the spotlight on another factor.

A factor that doesn’t focus on our biased thinking. A factor that doesn’t make us feel bad about our shortcomings. And a factor that actually inspires us to think better (rather than to just avoid mistakes).

He wanted to focus on insights.

Klein gives a simple equation that we should all be aware of:

[Performance Improvement = (Reduce Errors) + (Increase insights)]

For progress, humankind needs a balance of both the variables above. According to Klein, for too long we have been focusing on the ‘error reduction’ part and haven’t paid adequate attention to the ‘increase insights’ part. This book is a manual on how to do so.

What is remarkable about the book is the approach that Klein took to come up with his insight-generation model:

- Over several years, Klein put together a collection of 120 real-life stories of insight generation. These include mundane ideas generated over conversations at home, breakthroughs that led to remarkable innovations in science and staggering realisations that turned the tide of war

- He then studied these stories by categorising them under various heads and finding common patterns

- Finally, he came up with his own insight generation model

Klein boils down all insights into 5 categories – you could call them the 5Cs:

1. Connections

In this category, the thinker ‘connects’ a new piece of information in a different field and applies it to his or her own field. Here’s the story from the book that illustrates the connection approach:

Martin Chalfie (was) conducting research on the nervous system of worms. One day, almost twenty-five years ago, he walked into a casual lunchtime seminar in his department at Columbia University to hear a lecture outside his field of research.

An hour later he walked out with what turned out to be a million-dollar idea for a natural flashlight that would let him look inside living organisms to watch their biological processes in action. Chalfie’s insight was akin to the invention of the microscope, enabling researchers to see what had previously been invisible. In 2008, he received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work.

Chalfie realised that he could use an idea from that lunchtime seminar on bioluminescence and apply it to his field of work. By doing so, he ‘connected’ an idea from one field with another seemingly disparate field… But a field which did have something in common with the former.

One of the most famous ‘connection insights’ is how the Ford Assembly line (probably one of the biggest inventions in manufacturing) was inspired by a visit to a Chicago meatpacking operation, where animal carcasses were ‘dis-assembled’ as it went on a line.

2. Coincidences

Coincidence insights arise from observing several instances of an unusual occurrence, leading to a pattern. In the 1980s, Dr. Michael Gottlieb was a physician at UCLA, where he came across several unusual cases of patients with severely compromised immune systems:

When Michael Gottlieb encountered a second and then a third patient with a compromised immune system, he might have dismissed it. Instead he became suspicious. Something was going on, something he didn’t understand, and he needed to monitor it more carefully.

Gottlieb didn’t believe his patients had anything to do with each other. But the coincidence in their symptoms seemed important. And the men were all gay. Was there any significance in that? Quickly, the coincidence turned into a pattern, the deadly pattern of AIDS.

Coincidence insights tend to drive a lot of stereotypes. Beliefs like “People from X like to eat Y” or “All Xs tend to visit P” are driven by coincidence insights. These can, of course, be misleading.

3. Curiosities

Curiosities are similar to coincidences – they arise when we spot something unusual. But the key difference is it that it needs just one surprising occurrence instead of several for the thinker to investigate.

Wilhelm Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1885 came about through a curiosity. He was investigating cathode rays. He used a cardboard covering to prevent any light from escaping his apparatus.

Then he noticed that a barium platinocyanide screen across the room was glowing when his apparatus discharged cathode rays despite the cardboard covering. That was odd. So he stopped his investigation to look more carefully at what this was all about. After several weeks Roentgen satisfied himself that the effect was not due to the cathode rays but to some new form of light.

At the time, physicists appreciated a number of forms of radiation: visible, infrared, and ultraviolet. So X-rays could have been added to the list. But that didn’t happen. X-rays were greeted with disbelief. Lord Kelvin labeled them an elaborate hoax. One reason for the resistance was that a number of people used cathode ray equipment. If X-rays existed, surely others should have noticed them. (One researcher had noticed a glow but never accounted for it.) The skeptics eventually came around, and in 1901 Roentgen received the very first Nobel Prize in Physics.

Curiosity insights are driven by the ‘Vuja De’ mindset – the ability to spot the unusual in the mundane.

4. Contradictions

Contradiction insights arise when we find something that goes against a norm or deeply held belief.

If it sounds familiar to a Curiosity insight, here’s Klein:

Contradictions are different from curiosity insights. Curiosities make us wonder what’s going on, whereas contradictions make us doubt—“That can’t be right.”

The story of the cop figuring out about the stolen BMW was a Contradiction insight.

When the housing market was soaring in the US in the 2000s, some market experts were were deeply suspicious of the underlying fundamentals. Several of them believed that the ‘irrational exuberance’ in the market was contradictory with the ground situation and their basic reasoning.

Here’s the story of Steve Eisman, a wall-street insider, portrayed by Steve Carrell in the movie ‘The Big Short’:

When Eisman investigated, he found that the lenders had learned a lesson from the 1998 subprime crash. It was just a different lesson than he expected. When the subprime bubble burst in the late 1990s, the lenders went bankrupt because they had made bad loans to unworthy applicants and kept too much of those loans on their books.

Instead of learning not to make bad loans, the industry had learned not to keep the risky loans on their books. They sold the loans to Wall Street banks that repackaged them as bonds, found ways to mask the riskiness, and sold them to unwary investors. That’s when Eisman’s Tilt! reflex went into overdrive.

It reached even higher levels when he investigated the ratings agencies. In a conversation with a representative of Standard and Poor (S&P), Eisman asked what a drop in real estate prices would do to default rates. The S&P representative had no answer because the model the agency used for the housing market didn’t have any way to accept a negative number. Analysts just assumed housing prices would always increase.

5. Creative desperation

Sometimes insights emerge when we are in a desperate situation where we try several ideas till one works out.

Often, in such situations, when we are trying to solve a problem we find a breakthrough when we let go of a flawed assumption. Here’s a classic example:

The box-candle puzzle challenges subjects in an experiment to attach three candles to a door. They are given three small boxes, one containing three candles, the second containing three tacks, and the third containing three matches. Most subjects try to tack the candles to the wall, but this strategy fails miserably.

The trick is to tack the boxes to the door and set the candles on them.

The flawed assumption: The boxes are just receptacles for the items and don’t have any other role to play in the solution.

In this chapter, Klein narrates a thrilling story. In 1949, of a group of firemen in Montana, US, try to put down a forest fire, but are unfortunately consumed by it instead. Not all of them though. Some lucky folks survived. One of them – the leader, Warner Dodge – did an act of unimaginable creative desperation:

Wagner Dodge survived through creative desperation—an ingenious counterintuitive tactic. To escape the fire, he started a fire.

Dodge lit a fire in front of him, knowing that this escape fire would race uphill and he could take refuge in its ashes. He wet his handkerchief from his canteen and put it over his mouth and nose, then dived facedown into the ashes of the escape fire to isolate himself from any flammable vegetation. He was saved with less than a minute to spare.

But he could not persuade anyone to join him in the ashes. None of the others could make sense of what he was doing. He had invented a new tactic, but he never had a chance to describe it to his crew. As one of the two survivors put it, upon seeing Dodge light a fire, “we thought he must have gone nuts.”

Putting it all together

As per Klein’s analysis, Connections and Contradictions were the most common approaches seen in these stories:

I found Connection insights in 82% of the cases. Contradictions showed up in 38% of the cases. Coincidences played a role in 10% of the cases. Curiosities contributed to 7½%. Impasses and creative desperation were found in 25% of the cases.

(He’s of course tagged individual stories with multiple categories, which is why it totals up more than 100%).

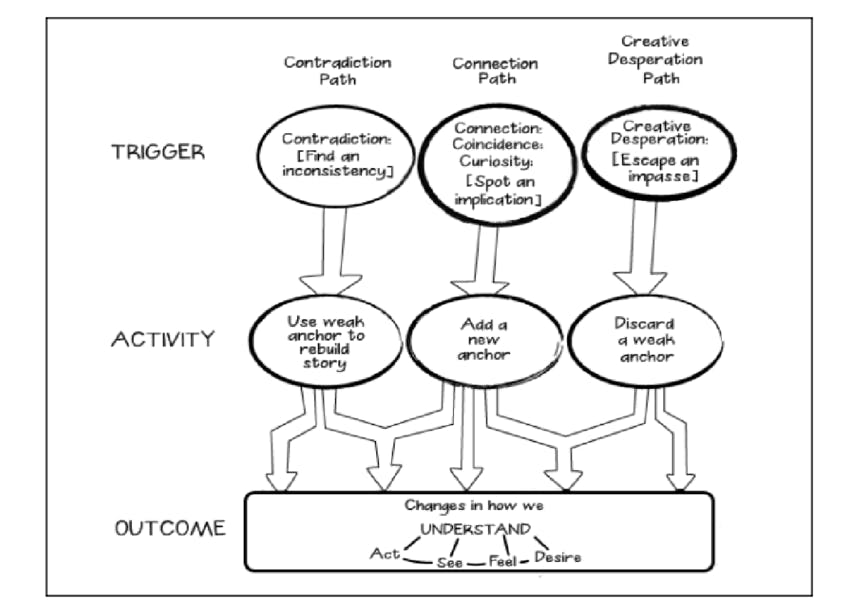

Finally, Klein combines all the insight pathways into a ‘Triple Path Model of Insight’

In addition to the above, the book also shares ideas on how to generate more insights for yourself and how to enable your teams and organisations to generate more insights.

It’s not an easy task at an organisational level – and Klein is pessimistic about the insight-generation capacity of large entities… According to him, as organisations grow larger, they employ more resources on reducing errors rather than improving insights.

Unfortunately, the two arrows often conflict with each other. The actions we take to reduce errors and uncertainty can get in the way of insights. Therefore, organizations are faced with a balancing act. Too often they become imbalanced and overemphasize the down arrow. They care more about reducing errors and uncertainty than about making discoveries.

He gives the example of the CIA:

The intelligence community has a unit to enforce tradecraft, the Office of Analytical Integrity and Standards. Its job is to reduce mistaken inferences and unsupported conclusions. When I have asked senior officials in the intelligence community if there is a parallel office to encourage insights, all I get are blank stares. Not only is there no such office; the officials have trouble imagining why they would need one.

Insights are the origin of all progress. If we want to grow sustainably, as we navigate challenges in a VUCA world, we need all the good insights we can get.

This book is a great resource that tells you how.

2. Podcast

a. Tim Ferriss with Naval Ravikant and Chris Dixon

In this fascinating conversation, Tim Ferriss (author, podcaster, Creator Economy God) talks with Naval Ravikant (founder of Angel List and Silicon Valley legend) and Chris Dixon (partner at VC firm a16z and evangelist of web3 and crypto).

They talk about all things crypto, NFTs and web3 – and they do a great job of using analogies and perspective to give us an idea of why this is such a massive deal.

“Denying and pushing back against NFTs and crypto is basically saying, ‘We’re not going to have a collectively owned future. We’re going to have a corporate-owned future, and we’re going to have a government-owned future’.” – Naval Ravikant

“This should be the greatest time in history for creative people.” Chris Dixon

We are at the cusp of the next big revolution in the internet – heck, one of the seminal moments of innovation in history – and this conversation is like getting a ringside view of the action from industry experts.

(H/t: Gururaj Sundaram)

3. Articles

a. The Past, Present and Future of Energy – Interview of Jason Crawford by Tomas Pueyo

I’ve been a big fan of Tomas Pueyo’s storytelling – especially those on geography.

This interview is with another brilliant writer Jason Crawford, who writes lucidly about the history of innovation and progress. (I found his writing similar to that of Matt Ridley, who’s book on the History of Innovation I had profiled some time back).

This interview shared some jaw-dropping future possibilities in a world of cheap power through nuclear fusion:

If you have enough energy, you can take saltwater from the ocean and turn it into clean water, to pure water. We could have water everywhere for human consumption, for agriculture. We could use this to irrigate the desert. We could reclaim the Sahara.

One of the interesting decarbonisation efforts, from a company called Terraformation, is to plant an enormous number of trees, say a trillion trees, and to do so by reclaiming the desert through desalinated water. They are planning to do it with solar power, but you could just as easily use nuclear—either fission or fusion.

And this comment really blew my mind:

The other thing we could do with enormous amounts of cheap energy is we can do the same thing to the atmosphere: we could pull trace elements out of the atmosphere, including, of course, carbon dioxide. We could go beyond the goal of stopping climate change. We could actually have a goal of climate control. I think the right long-term goal for humanity is climate control and weather control. We should be able to decide what is the ideal composition of the atmosphere and just set it to that, as if we had a thermostat.

b. US post-war Economic History by Morgan Housel

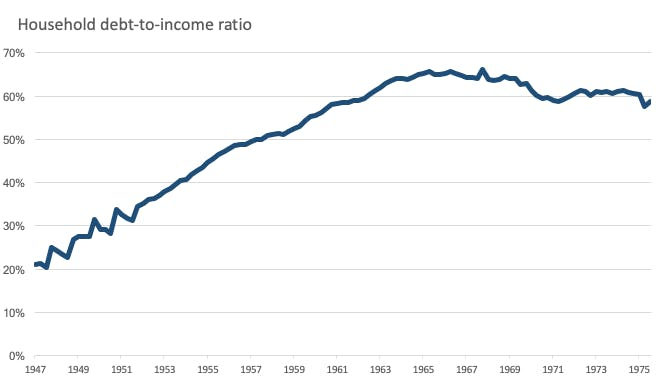

I try and read almost everything by Morgan Housel. In this longish piece, he does a great overview of the key drivers of the postwar economic boom in the US. Foremost among them was a massive credit boom. Regulation lowered interest rates and made it easier for returning soldiers to get mortgages.

What drove this credit boom? An unprecedented increase in home ownership. Here’s Housel quoting from the book ‘The Fifties’ by David Halberstam:

“They were confident in themselves and their futures in a way that [those] growing up in harder times found striking. They did not fear debt as their parents had … They differed from their parents not just in how much they made and what they owned but in their belief that the future had already arrived. As the first homeowners in their families, they brought a new excitement and pride with them to the store as they bought furniture or appliances — in other times young couples might have exhibited such feelings as they bought clothes for their first baby. It was as if the very accomplishment of owning a home reflected such an immense breakthrough that nothing was too good to buy for it.” – From ‘The Fifties’ by David Halberstam

Find any parallels to what is happening in India now? 🙂

c. Three darts of pain by Andrew Wilkinson

This tweet thread hit me deep inside – because I go through it all the time.

Humans have the tendency to amplify the pain that a bad event can bring about. Say you have a get-together at home with friends for which you need to order food. You’re excited about the get-together but have a bunch of worries about the food order: What if the food you order is not up to the mark? What if it falls short? Or what if, in fear, you end up ordering too much, leading to wastage? What if the order isn’t delivered on time?

In an ideal world, you should feel bad only if one of those (low-probability) events come to pass. In reality, you might feel the ‘pain of fear’ at three points in time:

- Before the event: You play out scenarios in your mind and feel the pain of things getting botched up (despite your significant past experience in these events all going great)

- The actual event: There might be a rare occurrence that your actual order quantity or quality might not be up to the mark. This is the real pain-generating event (Let’s face it, we are all social creatures).

- The post-event reaction: The pain can get amplified based on how you (not your guests, you) react to the issue. Almost all guests don’t bother and in fact might be willing to support you to rectify the anomaly. But you might go through pangs of guilt, shame, fear (of ‘what will people say’) even as you process the event’s aftermath. It doesn’t have to be so. People are busy. They are not going to be obsessed with the food in your party. And even if they are, you shouldn’t worry about what such people think!

In this tweet thread, Andy Wilkinson (co-founder of buyout firm, Tiny Capital) calls the above as the “three darts of pain” and states that it’s only the second dart (which is the actual negative event) which should be painful. We humans have an immense capacity to amplify our pain!

I’m grateful to Andy for giving me the vocabulary to understand my tendency to over-think and over-worry. Incredibly insightful stuff.

4. Video

a. ‘To send or NOT to send – to School’ by Aiyyo Shraddha (3:02)

Uff, what a talent this girl is. The observational skills, the scripting, the words, the expressions, the accent. Hilarious.

That’s it folks: my recommended reads, listens and views for the month.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay