The most critical storytelling lesson from Bollywood’s biggest hit

A monster hit

Dangal’s unprecedented success – a worldwide gross of more than $300M – may have surprised even its makers. Clearly the film industry was stunned – for instance when Kangana Ranaut was asked if she was jealous of any other movie’s success at the ‘Koffee with Karan’ show, she mock-cribbed: “… the fact that Dangal made so much money… like so much?!” How did a movie starring new actors depicting two female athletes from rural Haryana playing a low-popularity sport become such a global monster hit?

Clearly, among many factors, it was the story that resonated strongly with the audience – especially some critical dramatic scenes (take a bow, Nitesh Tiwari).

You would especially remember that stirring final match… when the protagonist, Geeta Phogat is up against a tough Australian opponent and seems to be down in the dumps. Her inspiring father is missing (having been locked up by a jealous coach) and she’s trailing 1-5 in the deciding final round. With a few seconds to go, she remembers his advice about a daring manoeuver, which she flawlessly executes, dramatically winning the match and the coveted gold medal.

It’s quite amazing to think that these events – the tough final, the missing dad, the 1-5 situation, and the magical “indradhanush move” – actually occurred… Except that they didn’t.

Based on a true story (with lots of made up stuff)

Here’s the reality of that final match: Geeta Phogat steamrolled her opponent 1-0, 7-0. Her father was very much in the stands, beaming with pride. Many other ‘facts’ in the movie are made up: the villainous coach, Geeta’s lack of international medals before this match, the use of the “Indradhanush” move…

Now, I know what you’re thinking. When we see a statement like “based on a true story”, we all realise that it won’t be a scene-by-scene narration of actual events. Clearly, movie writers have to entertain, and need to introduce dramatic elements.

But this was a story already brimming with much dramatic potential – a girl from a small patriarchal village, defying all norms to win at a prestigious global tournament. Why then, did their writers feel the need to introduce so many additional fictional elements?

The answer my friend, is conflict.

Manufacturing conflict

The key storytelling secret from Dangal is how they astutely manufactured the right amount of conflict to make the story engaging. Every time you got the feeling that things were going great for the protagonists, an element of conflict would be introduced, which would require them to struggle, dig deep within and show character – before they reached the (preferably happy) resolution. In short, it wasn’t enough that Geeta won – the fact that she won with almost-impossible odds stacked against her made the victory sweeter.

Let’s revisit the movie’s plot – it almost reads like a see-saw of conflict and resolution:

Why do we seek such strong conflict in a story?

A cricket example

In game 3 of a recent India-Australia one-day series, India were cruising at 139/0 from 21 overs chasing 294. Rohit Sharma and Ajinkya Rahane were toying with the bowlers. I was losing interest in the game, almost feeling sorry for the Australians. As if hearing my thoughts, fate obliged – India lost a couple of quick wickets and later two more, putting the game in balance. Now things were interesting. Hardik Pandya (and Manish Pandey) went through a period of struggle, persevered and later emerged as the heroes, taking India to victory with a mix of calm and aggression. The middle-order struggle made the win sweeter.

This seems somewhat counter-intuitive – more than just seeing our side win, we want to see them struggle and win. The odds have to be stacked against (the more the better) before we see them taste victory. And sometimes that struggle is more memorable than a win (for example Sachin almost winning us the famous 1999 Chennai test against Pakistan, despite a bad back). I bet you’d remember that game more than many easy victories in random one-sided matches.

In short, conflict matters, sometimes more than the outcome.

Implication at work: for a pitch or performance review presentation

You may say: “That’s all good, but we can’t be creating facts to make our stories interesting… (unless you are KPMG in South Africa!). Can we use this principle at work?”

Yes we can. Consider the following two situations:

1. You are making a pitch presentation for a new product, startup or business initiative

2. You are giving a presentation showcasing the performance of your division/company for the last quarter/year

In #1 above, you would be selling a solution to some customer problem. The storytelling lesson: Don’t describe the solution before you describe the problem/conflict in vivid, relatable terms. A couple of great examples of this from real life:

– Steve Jobs’ iconic presentation for the first iPhone. Watch this video, where he lays down the landscape of existing smartphones and the challenges they pose (the ‘conflict’) – and how the iPhone will be a leapfrog product (the ‘resolution’). He uses the ‘conflict-resolution’ framework later too, when he talks about the current sub-optimal UI vs. the revolutionary one on the iPhone

– The present-day Jobs, Elon Musk uses this framework too. Witness the Tesla Powerwall presentation – at the very beginning, he describes how the current approach of energy production is so flawed, leading to high CO2 emissions. He then describes additional challenges such as the peak usage issue. Only after that, he moves on to the solution: a solar-powered battery pack for the home. As he describes further features/versions of the product, he always prefaces it with the problem that it is meant to solve.

In fact, this approach of structuring a pitch presentation (conflict-resolution; conflict-resolution) is documented by the well-known storytelling expert, Nancy Duarte. Watch her TED talk on the ‘Secret Structure of Great Talks’, where she discovers the “shape” of a memorable presentation. (from 5:14 onwards)

In case of #2 above (performance review presentations), you are describing key achievements in the past period. The issue with those kind of presentations is – once we achieve something we tend to undermine the challenge or effort that went into it. (Of course, some of us are gifted at creating a big story out of no real achievement!). But typically in my experience, good, solid achievers tend to undermine their own work by not showcasing the challenge appropriately.

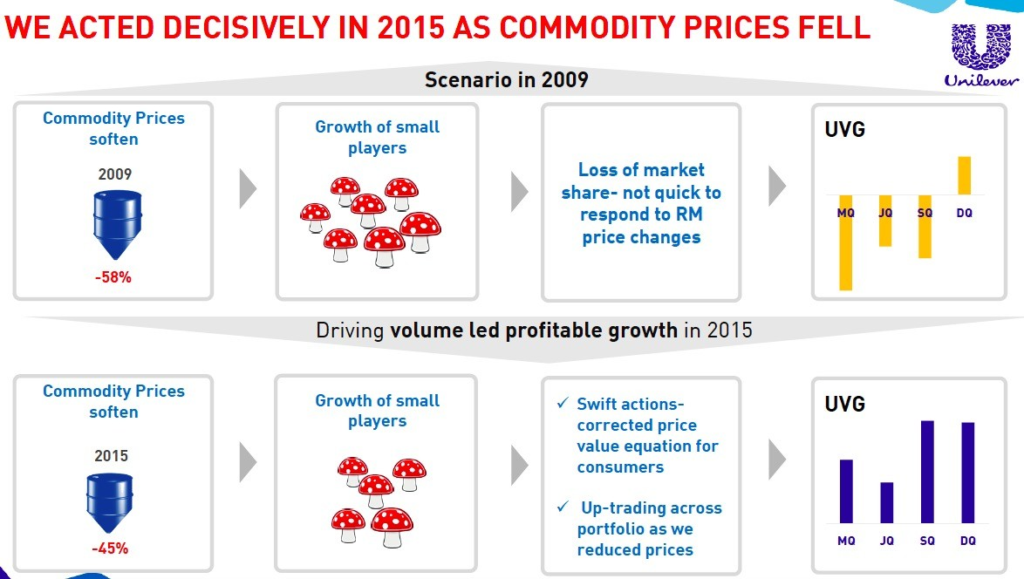

A great example of where this was done well, was the HUL investor presentation that we had discussed in an earlier post. Before talking about its achievement of strong volume growth in 3 out of 4 quarters, HUL described the challenge – of how in the same situation 6 years back, it had seen falling volumes. Highlighting that challenge makes the achievement stand out in context.

Summing up: Showcase the conflict before the resolution

So that’s the final lesson from this post:

Or, how about this: Show the conflict/challenge/struggle vividly before showing the resolution (in the form of your solution or achievement).

You may not be helming the next global blockbuster, but you can sure learn from India’s biggest hit and win that medal in your next presentation!